DownUnderCTF 2022 – ezpz-rev

Grid puzzles aren't that easy.

This was a fun little break from all the school work piling up. School is tiring, just like something else...

Challenge Description

CTFing is tiring. Take a break with this easy puzzle!

Note: The binary and server in this challenge are the same as "ezpz-pwn".

The description is rather terse. But it seems like the same binary is used for two challenges.

The binary is available on the DownUnderCTF repository. If you want to have a stab at the challenge, go for it!

Writeup

As with all reverse challenges, let’s first throw the executable into a decompiler and see what crops up. I'll be using Ghidra, a free open-source decompiler perfect for ezpz challenges.

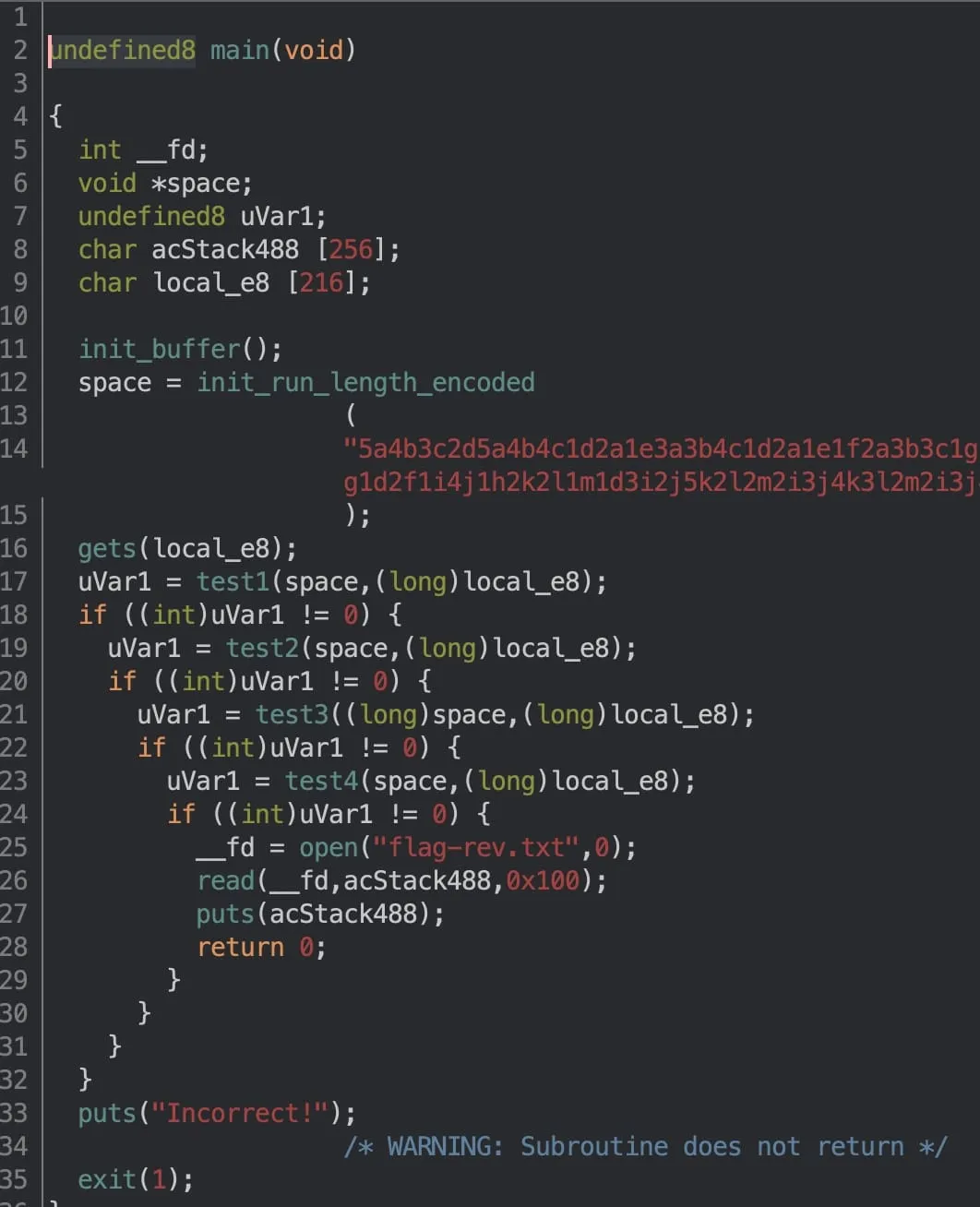

Navigating to main, we see a function call, a gets (for reading user input), and a chain of four if-statements barring our way to some statements which print out the contents of flag-rev.txt (presumably the flag for this reverse challenge).

The most important functions to crack are the four guarding the file read. But we’ll take a look at the initialisation procedures first since they provide some helpful context towards understanding the program. Along the way, we’ll incrementally build a z3 logic solver to emulate/reverse each function.

Initialisation

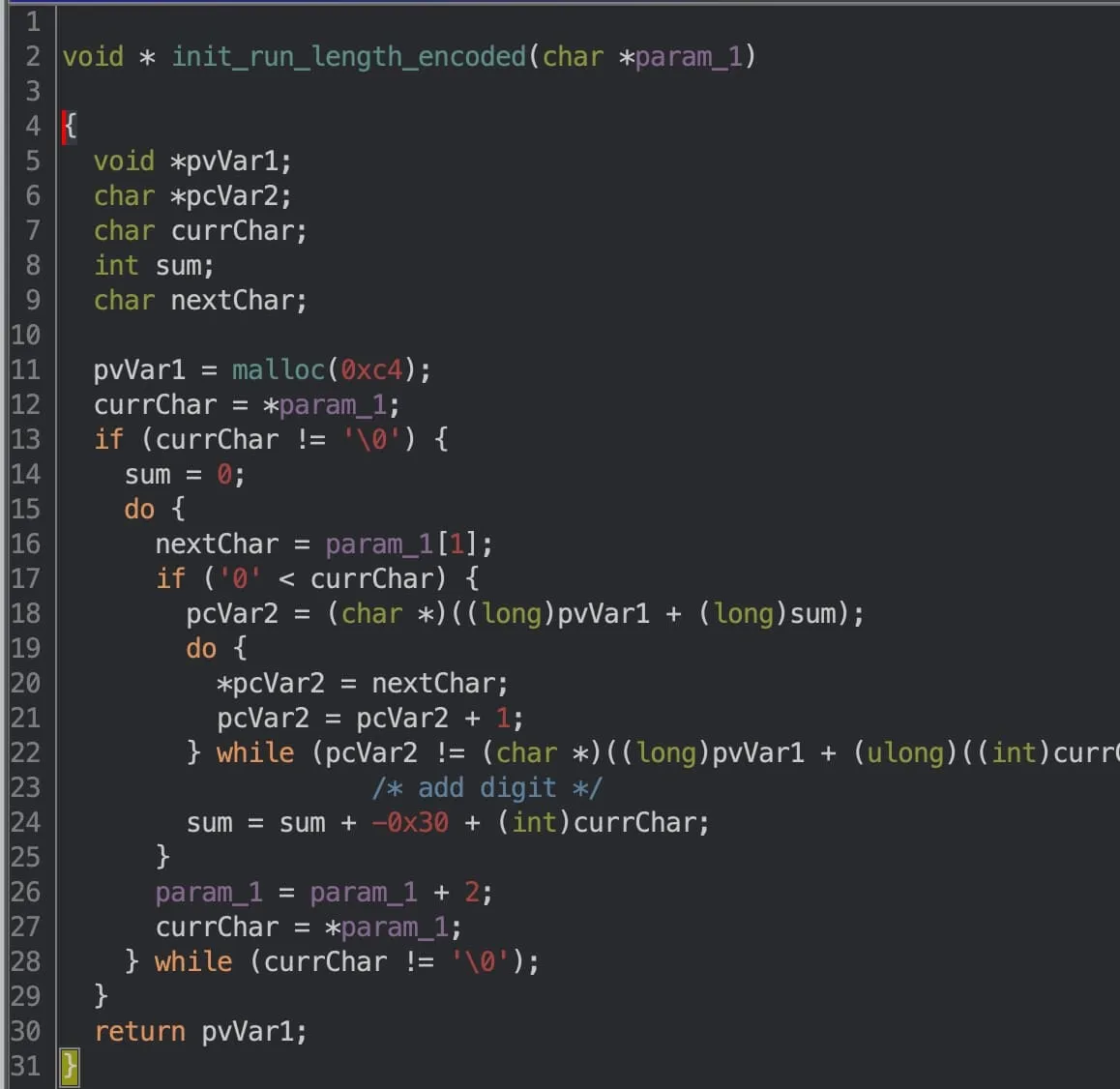

The first initialisation function modifies some options for the stdin/stdout buffers. Pretty standard C-style CTF stuff. The second initialisation function is much more interesting. Here’s a screenshot of the decompiled program:

Decompilers are great and all, but the lack of useful variable names, comments, and readability can be a pain. Here’s a cleaned up version:

In effect, the function initialises an array of chars by decoding a run-length encoded string. For example, the string 5a4b3c2d gets expanded to aaaaabbbbcccdd. Of course, the encoded string used is much longer, and it turns out that it fills all 196 (0xc4) chars allocated. There are a few more things I’d like to point out:

- 196 (0xc4) is a number that pops up a lot in this binary.

- Although typical run-length encoded strings may have more than 9 digits packed together (e.g. 12c13e42f), the implementation above assumes a run-length of at most 9 (i.e. one digit).

- Interestingly, the characters encoded only range from

aton. We’ll see how these come into play later on.

We can begin writing our solve script! Let’s perform this initialisation and decode the string into a chars variable.

The First and Second Guards: Move Along Now, Nothing to See Here

If the initialisation procedures are the appetiser, then the four guards are the main course.

I’ll be using the term guards and tests interchangeably. Guards are a term I’m borrowing from CS and functional programming. It’s basically an elevated if-statement.

Each guard checks if the input satisfies some condition. If the condition passes, the guard function returns 1, else 0. To get to the delicious dessert (the flag :P), we want all four functions to return 1.

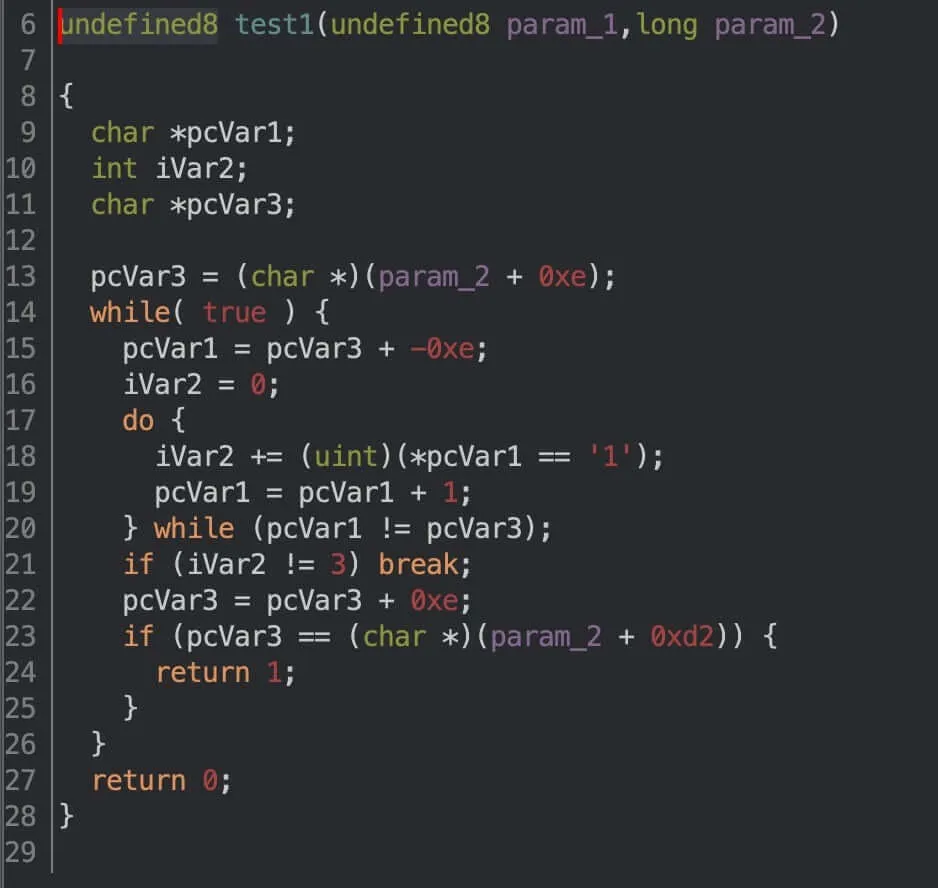

Easier said than done. Let’s start with the first function and see what it decompiles into.

Here’s a more readable version:

Essentially, it groups input into blocks of 14 chars; then it checks if the number of '1's in each block is exactly three. If any check is false, then the function returns 0, meaning we have failed miserably.

We can easily model this symbolically in z3. We’ll first create 196 symbols, each representing one character in input. Then, we'll create a z3 solver object: this is our interface to z3’s automagical solver. Through the solver, we can add constraints, remove constraints, generate concrete values, etc.

Our simplest constraint is our input constraint. For this program, we’ll limit our symbols to take on only 0s and 1s. Why? Because it is easy for z3 to sum integer symbols. This way, if we want to count the number of 1s in a list, we can just call z3.Sum on it.

We then add the constraints of the first guard by selecting groups of 14 elements using Python’s slice notation inputs[size*i:size*(i+1)] and constrain it to 3.

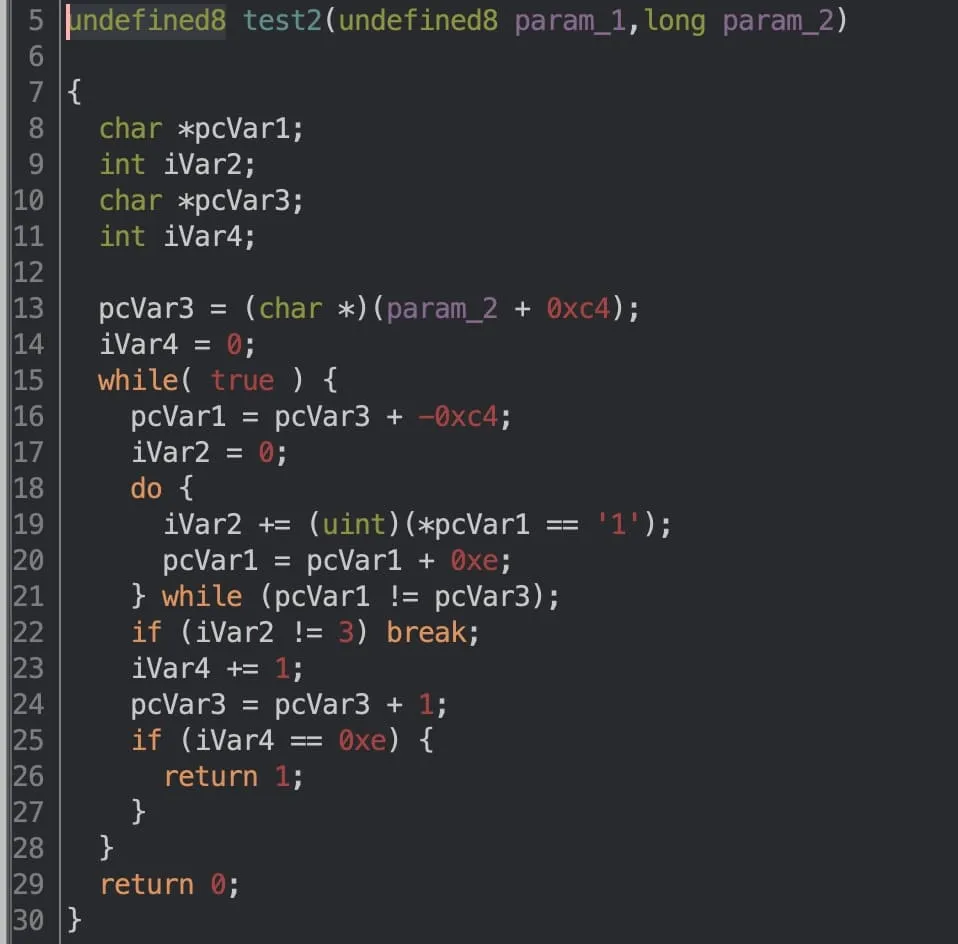

Nifty! Let’s see what the second function looks like.

This looks surprisingly similar to the first test. In fact, the only thing that really changed is the order of the loops. Observe how the first function moves along the grid in a row-major fashion, whereas the second function moves in a column-major fashion.

It may begin to dawn on you that the nested loops are hinting at a grid-like structure, a 14-by-14 2D array of characters. This realisation is pretty crucial, as it’ll help us reverse our last two functions much faster.

Let’s add these constraints to our solve script:

inputs[i::size] is Python slice notation to iterate beginning from i and picking every size elements, e.g. [*range(10)][1::3] == [1, 4, 7].

Onto the next function!

The Third Guard: Please Wear Your Mask

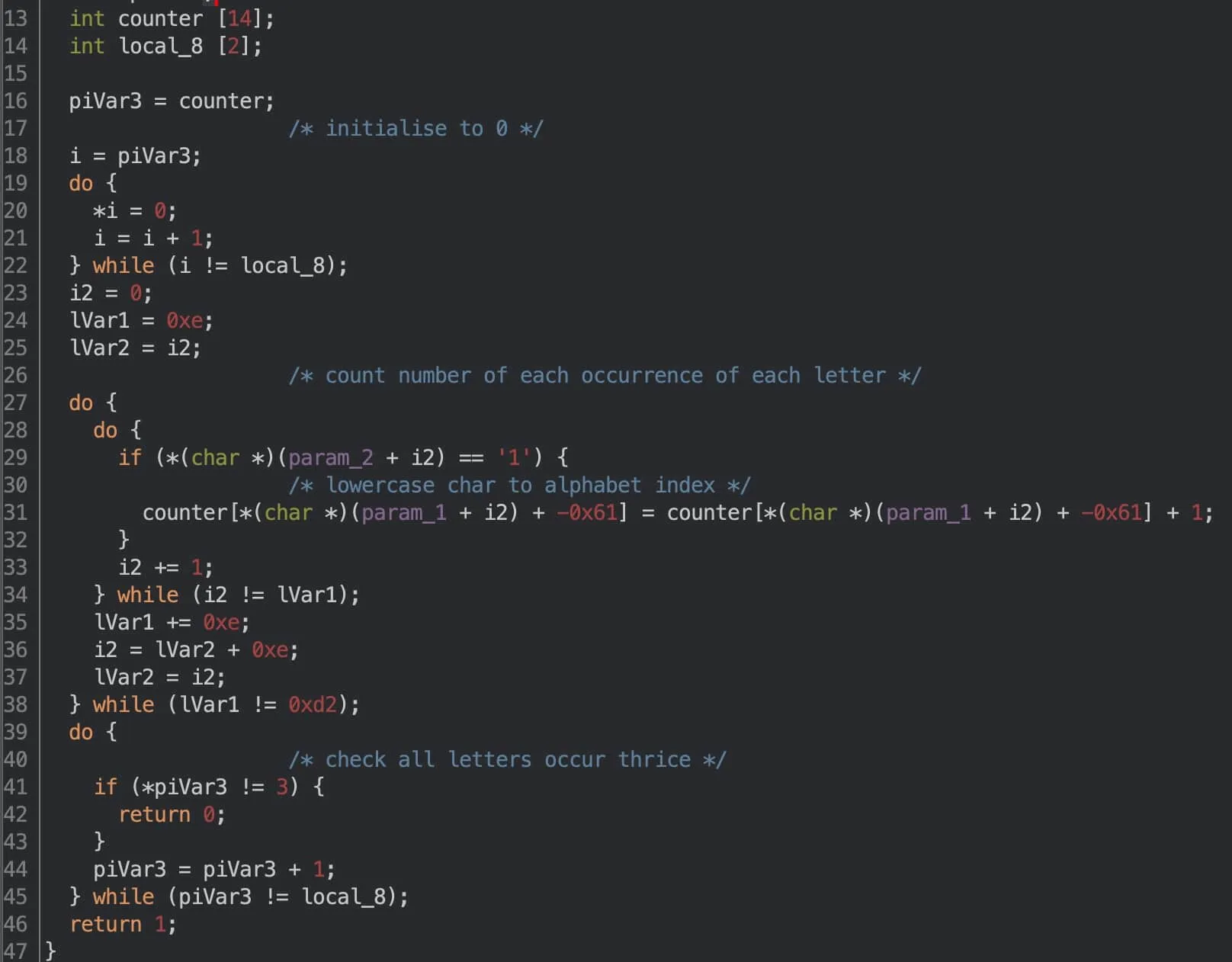

Using our vectorised 1D representation, we can simplify the above to:

This initialises an array of 14 integers that serve as counters. This is followed by two loops. In the first loop, we mask the input and initialised characters, then count the number occurrences of each character. In the second loop, we simply check that all counters equal 3, meaning each letter appears exactly three times in the masked string.

By “mask”, I mean something like bitwise-and, but for characters. For example, abcdefg masked with 1011001 would be a cd g, as only those four letters have 1 associated with them. Alternatively, you can think of the 0s as masks hiding letters from sight, just like how face masks hide mouths.

This is the first of the four functions which actually combines both the user input and the character grid used in initialisation. The previous two functions performed checks only on the user input, but now we begin to see how the two relate.

Also recall that the letters initialised range from a to n, and in fact n is the 14th letter of the alphabet. 14 rows, 14 columns, 14 letters, checking if everything equals 3… seems a little sus. Maybe the challenge authors are hinting at the number 42, the answer to life and everything in the universe? Is this the true reverse behind this challenge?

Anyway, let’s try to add these constraints to z3. In proper reverse fashion, instead of first checking the user input like the original function, we’ll start with the letters. We’ll collect the indices containing a letter (say 'a'), then collect all the input symbols associated with those indices, sum them, and constrain them to three.

Great! Three down, one to go.

The Fourth Guard: Wonky Jumps and Guesswork

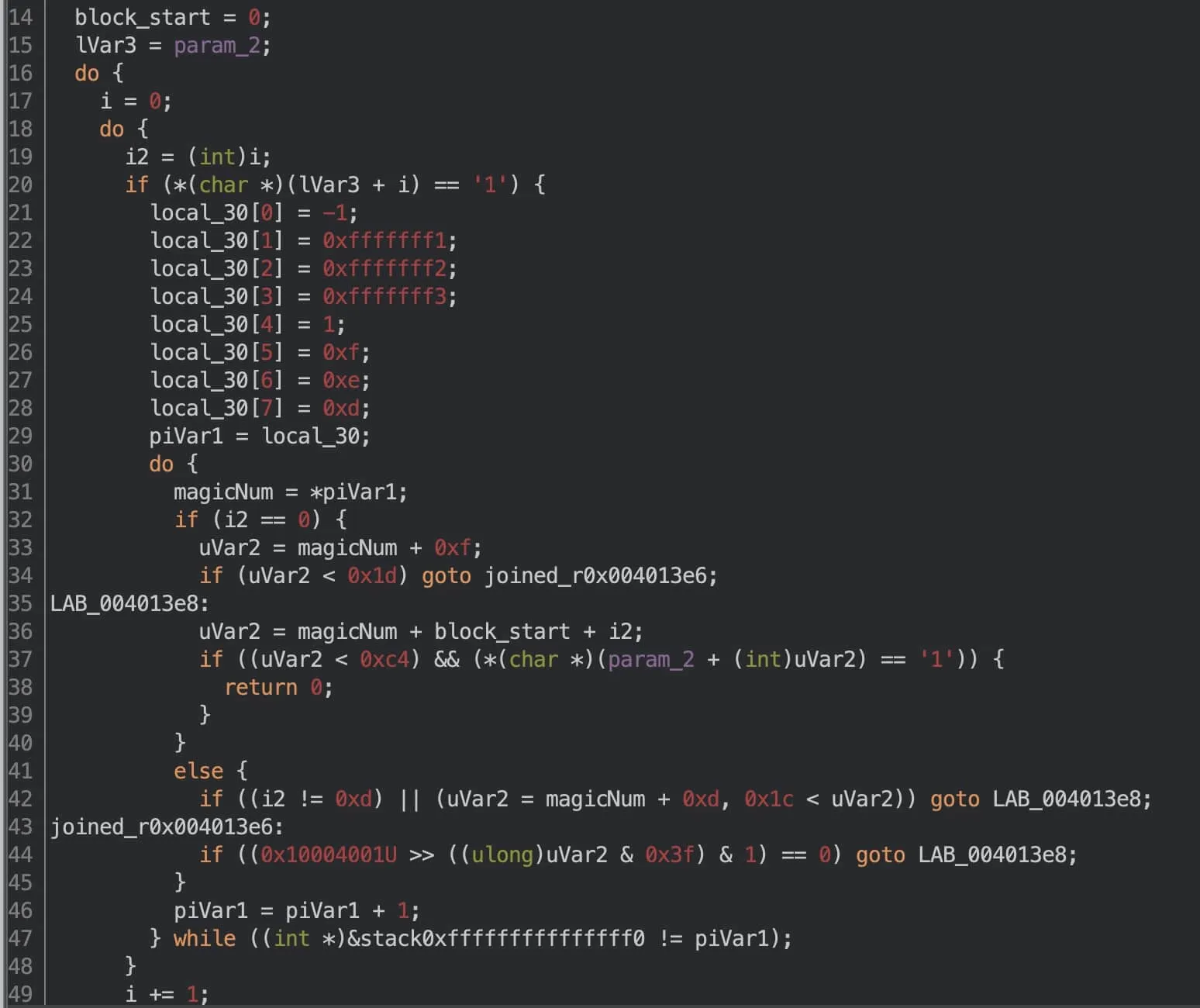

Here's a snippet of the fourth guard:

The first half is understandable... But the rest... Hoh! What an eye sore! What’s the jump doin— I can’t even— ugnahfpwifhlqufjcjwalfhwowjrvkaufjwp.

As far as my monkey brain understands, the function iterates through every grid cell, and if it equals 1, performs some complicated check in an inner loop. At this point, I tried to understand what the inner loop was doing. Not much success. Looking at the decompiled output, keep in mind that 0xfffffff1 is only the unsigned interpretation. There is also the signed interpretation, which in this case is -15.

I then trained my eyes on the other "magic constants" in the inner loop and focused all my reverse powers by staring the numbers down. -1, -15, -14, -13, 1, 15, 14, 13. Hmm…

Ooh! Perhaps it’s checking adjacent cells orthodiagonally (i.e. orthogonal + diagonal)? If you’ve implemented a Minesweeper game before, you’ll know where I’m going :P. Indexing i - 14 would pick the cell above cell i, since each row is 14 cells wide. Similarly, i + 14 would pick the cell below. i + 15 would pick the bottom-right cell, and i - 1 would pick the left cell. Interesting!

The other complicated checks, I presume, are out-of-bound checks. For example, if we’re at i == 0 (the top-left corner), then the only adjacent cells are i + 1, i + 14, and i + 15. Anything else would go outside the array. After guessing this, I didn’t bother figuring out whether the decompiled loops actually follow this logic. Terrible software engineering practice, but eh, we’re playing reverse, so might as well try it.

To the solver! For each symbol, we’ll add constraints saying, “If this cell is 1, its surrounding cells can’t be 1.” We’ll use z3.Implies to encode this logic. We only consider cells orthodiagonal to the current cell and within grid bounds.

And with that, we’ve defeated the four guards! Huzzah!

The Final Touch

All that’s left is to let z3 solve our constraints and generate concrete values for our symbols. We’ll push these concrete values into a payload variable and print it out.

We obtained a z3 model from the solver by calling s.model() and evaluated our symbols to produce concrete integer 1s and 0s by calling m.eval(sym).as_long().

After feeding this to the server, we obtain the flag. Yippee!

For an “easy” challenge, I definitely spent too much time on this. I wasted some time switching between a pure z3 logic solver and a full-blown angr solver, finding out angr was taking too long, and spamming Ctrl+Z. I could’ve spent this time sleeping instead. 😕

One of the difficulties of reverse is trying to understand both the high-level aspects and low-level aspects. Sometimes skimming through the program structure helps. Other times, getting deep into the nitty-gritty aspects may help us recognise some familiar elements. This challenge was a fun little exercise to practice these two approaches.

Solve Script

Flag

Payload

Flag

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.

![Thumbnail for N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]](/img/posts/programming/concepts/subtype-metaprogramming/assets/thumbnail-512w.webp)