TAMUctf 2022 – Labyrinth

Using CFGs to solve a control-flow maze.

Challenge Description

To get the flag you'll need to get to the end of a maz- five randomly generated mazes within five minutes.

This is an automatic reversing challenge. You will be provided an ELF as a hex string. You should analyze it, construct an input to make it terminate with

exit(0), and then respond with your input in the same format. You will need to solve five binaries within a five minute timeout.

Write-Up

Preliminary Observations and Analysis

Unlike other reverse challenges, this one requires us to connect to a server and auto-hack not one, but five binaries. We're provided with this template:

Modifying the template slightly, we run and download a couple binaries for analysis.

As a first step, we'll run checksec to see what securities are in place.

It appears that PIE is enabled. We'll make a mental note of this, since this may mess with function addresses.

What is PIE? Sadly, not the scrumptious dessert. Position-independent executable is a security mechanism whereby on starting an application, the OS will offset the assembly sections (.data, .text, etc.).

Next, we decompile our elves using Ghidra and make some observations.

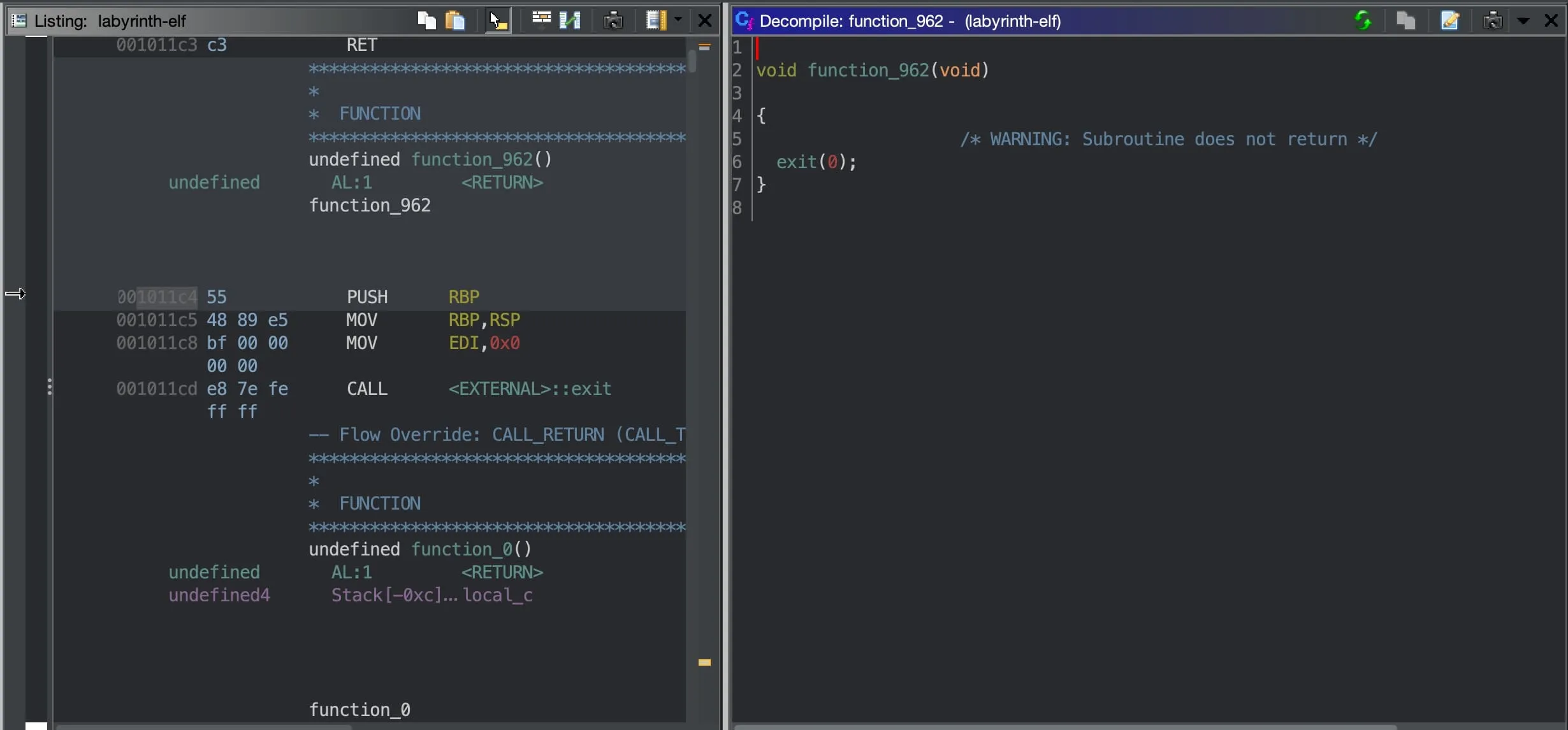

Only one function contains exit(0).

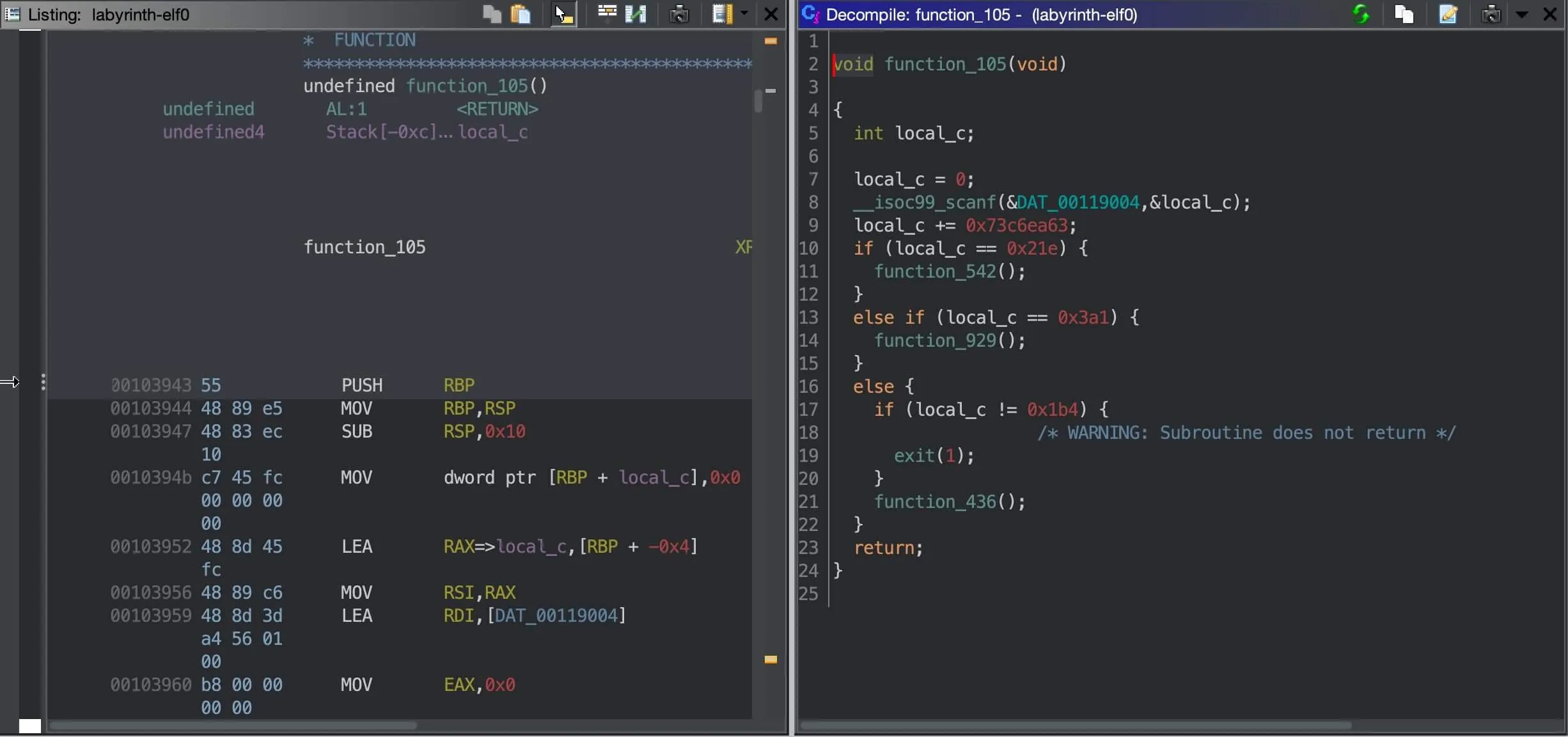

Other functions seem to perform some sort of check and lead to more functions.

- Each binary contains a thousand (1000) functions (excluding

main). The symbols arefunction_0,function_1,function_2, and so on. - Each of these functions will:

- Call

scanf("%u\n", ...)(read 4 bytes into a stack variable), and - Branch (if, else-if, else) into two or more paths.

- The branch conditions come in some form of arithmetic check. For example,

input == 0x1c1,input ^ 0xc213504e == 0x142,input < 0x143,input - 0x5173cdc3 == 0x28b. - Each branch will either

exit(1)- or call another function from the 1000 functions.

- The number of branches, numbers used in the conditions, and order of conditions are random.

- Call

- All 1000 functions are laid next to each other in memory.

mainis always at0x101155and starts by calling one of the 1000 functions. The function call is not fixed (i.e. we can't be certain about the address).- Only one function calls

exit(0)and this function is always at address0x1011c4.

To "solve" an elf, we need to give an appropriate input at each step of the function such that the correct branch and path are taken. In other words, we need to trace the right path out of the maze. We need to solve 5 elves to get the flag. We only have five minutes for five elves. Solving this without any automation seems next to impossible. Thankfully, we have angr.

What is angr?

angr is a python library which simulates machine code while keeping track of program state. Its exploration features are useful to find the input corresponding to a given output.

Coding

As a preliminary step, we'll import angr, load the project, and set some constants.

Ghidra will load PIE assembly at offset 0x100000, but angr loads it at 0x400000 by default. So all addresses in the previous section were offset by an additional 0x300000 to account for this difference. There's a way to make angr load at a custom offset, but I forgot what the option was called. (But the option exists!)

Now we'll try some good ol' angr explore() and see what turns up.

explore() is the most straightforward command in angr. With the find=tar_addr parameter, we tell explore() to simulate and look for states which will execute the instruction at tar_addr.

Path Explosion

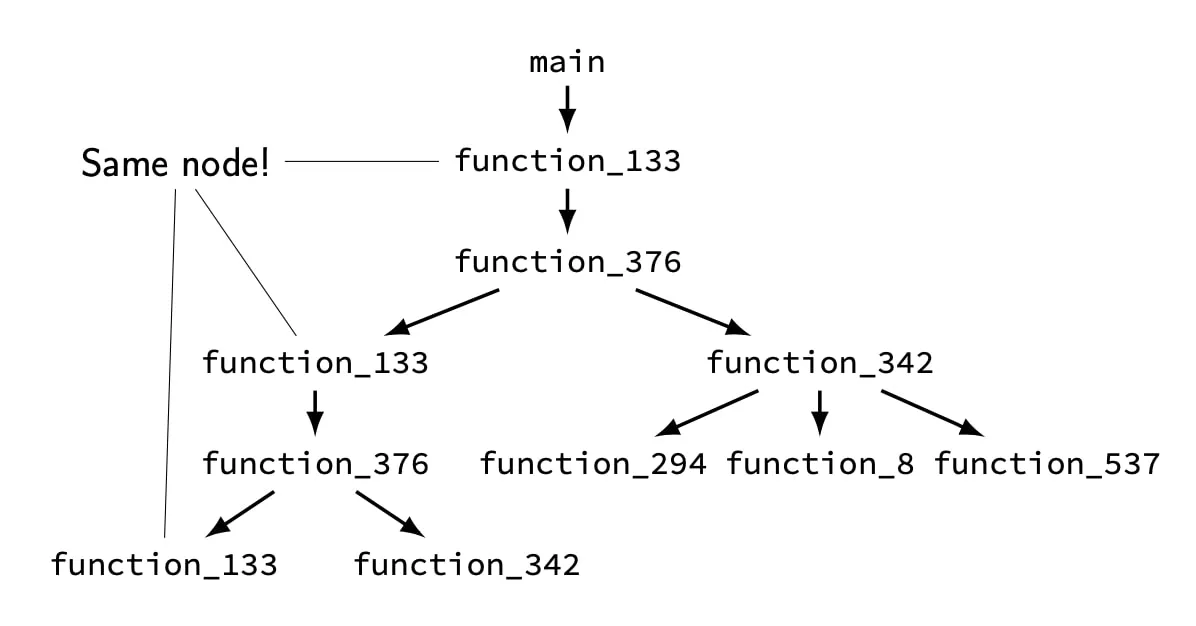

Unfortunately, this takes forever to run due to path explosion. Notice how the control flow makes the paths diverge in one of the binaries:

Now angr is pretty smart, but not too smart. angr will simulate all paths and if it encounters a branch, it will simulate both branches together. However, it will treat the function_133 branches as separate states...

To get a more concrete view of paths exploding, Gru tried calling simgr.run(n=50)—which simulates 50 steps...

90 active states is quite a lot! Usually we'd want to limit ourselves to around 10 active states to ensure good simulation speed.

With 50 steps and already 90 active states, the situation is pretty dismal. We'll need to find a better way of getting to the target address.

CFGs to the Rescue

Control flow graphs (CFGs) are directed graphs where nodes are blocks of code and edges indicate the direction the code can take. By translating the program into a graph, we can utilise the many graph algorithms at our disposal. In particular, we're interested in the shortest path between a start node and target node.

angr comes with a bundle of analysis modules; these include two CFG analysis strategies: CFGFast and CFGEmulated. The former analyses the program statically (without actually simulating the code!), whereas the latter analyses the program dynamically (i.e. by simulating the code).

Since the labyrinth elf only contains simple if-statements and function calls, and no obfuscation or complicated redirection whatsoever, we can construct a CFG statically!

Working with graphs and nodes in angr is fairly straightforward. angr CFGs are just instances of networkx graphs (a python graph library), so we'll need to import it to use its handy shortest_path function.

Now that we have a direct sequence of nodes from main to our exit(0) function, we just need to guide angr's simulation manager along the path, function-by-function.

Our last step is to get the input used. angr's constraint solver should have it figured out.

On my computer, this solve process takes roughly 30-40 seconds... which is good enough, since it falls within the allotted time of one minute per solve. Putting it together with the solver template and running it, the server kindly hands us the flag!

Solve Script

Flag

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.

![Thumbnail for N[Subtype Metaprogramming] is N[Mostly Harmless]](/img/posts/programming/concepts/subtype-metaprogramming/assets/thumbnail-512w.webp)