Digital Audio Synthesis for Dummies: Part 2

Generating audio signals for great good through additive synthesis and wavetable synthesis.

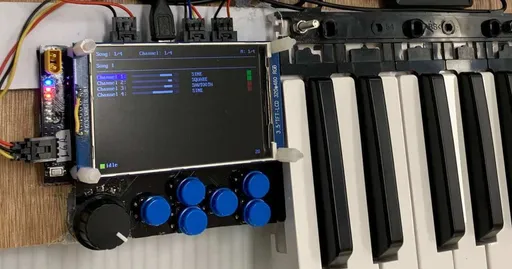

This is the second post in a series of posts on Digital Audio Processing. Similar to the previous post, this post stems from a lil’ MIDI keyboard project I worked on last semester and is an attempt to share the knowledge I've gained with others. This post will dive into the wonderful world of audio synthesis and introduce two important synthesis techniques: additive synthesis and wavetable synthesis.

Audio Synthesis 🎶

Where do audio signals come from? Our signal might be…

- recorded. Sound waves are picked up by special hardware (e.g. a microphone) and translated to a digital signal through an ADC.

- loaded from a file. There are many audio formats out there, but the most common ones are .wav and .mp3. The .wav format is simple: just store the samples as-is. Other formats compress audio to achieve smaller file sizes (which in turn, means faster upload/download speeds).

- synthesised. We generate audio out of thin air (or rather, code and electronics).

I’ll mainly focus on synthesis. We’ll start by finding out how to generate a single tone, then learn how to generate multiple tones simultaneously.

Buffering 📦

A naive approach to generate audio might be:

- Process one sample

- Feed it to the DAC/speaker

But there are several issues with this: function call overhead may impact performance, and we have little room left to do other things. For the sound to play smoothly while sampling at 44100Hz, each sample needs to be delivered within $\frac{1}{44100}$ s = $22.6$ µs.

A better approach is to use a buffer and work in batches. The buffer will hold onto our samples before feeding it to the speaker.

- Process $N$ samples and store them in a buffer

- Feed all $N$ samples to the DAC/speaker

We'll focus more on step 1 (processing) for now. We'll cover step 2 (output) in the next post.

In a previous post, we discussed quantisation and how different representations (such as integers and floats) are suited for different tasks. Integers are discrete numbers, while floats are (imprecise) real numbers. Since we're concerned with audio processing, we'll be using floats and quantising from -1 to 1.

In C/C++, we can generate a sine tone like so:

And that’s it—we’ve just whooshed pure sine tone goodness from nothing! Granted, there are some flaws with this method (it could be more efficient, and the signal clicks when repeated); but hey, it demonstrates synthesis.

Note on Buffers: Usually, the buffer size is medium-sized power of 2 (e.g. 512, 1024, 2048, 4096...). This enhances cache loads and processing speed (dividing by a power of 2 is super easy for processors!).1

The Fourier Theorem 📊

One fundamental theorem in signal processing is the Fourier Theorem, which relates to the composition of signals. It can be summarised into:

Any periodic signal can be broken down into a sum of sine waves.

We can express this mathematically as $$ f(x) = a_0\sin(f_0x + b_0) + a_1\sin(f_1x + b_1) + \cdots + a_n\sin(f_nx + b_n) $$ where $a_i$, $f_i$, and $b_i$ are the amplitude, frequency, and phase of each constituent sine wave.

The Fourier Theorem and Fourier Transform are ubiquitous in modern day technology. It is the basis for many audio processing techniques such as filtering, equalisation, and noise cancellation. By manipulating the individual sine waves that make up a sound, we can alter its characteristics and create new sounds. The Fourier Transform is also a key component in compression, such as the JPG image format.

What’s cool about this theorem is that we can apply it the other way: any periodic signal can be generated by adding sine waves. This lays the groundwork for additive synthesis and generating audio with multiple pitches (e.g. a chord).

Additive Synthesis ➕

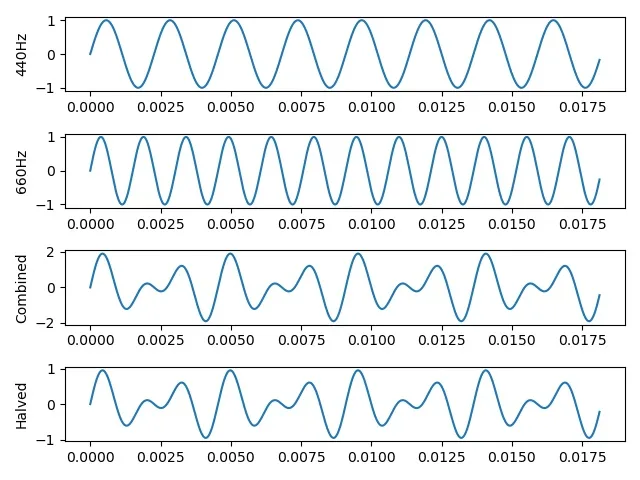

The principle of additive synthesis is pretty straightforward: signals can be combined by adding samples along time.

Example of additive synthesis. The first and second signal show pure sine tones at 440Hz ($s_1$) and 660Hz ($s_2$). The third signal adds the two signals ($s_1 + s_2$). The fourth signal scales the third signal down to fit within $[-1, 1]$ ($(s_1 + s_2) / 2$). (Source Code)

To sound another pitch, we simply add a second sine wave to the buffer.

Again, the code above populates the buffer with 1024 samples of audio. But this time, we introduced a second frequency freq2 and added a second sample to the buffer. We also made sure to scale the resulting sample back down to the $[-1, 1]$ range by multiplying each sample by 0.5.

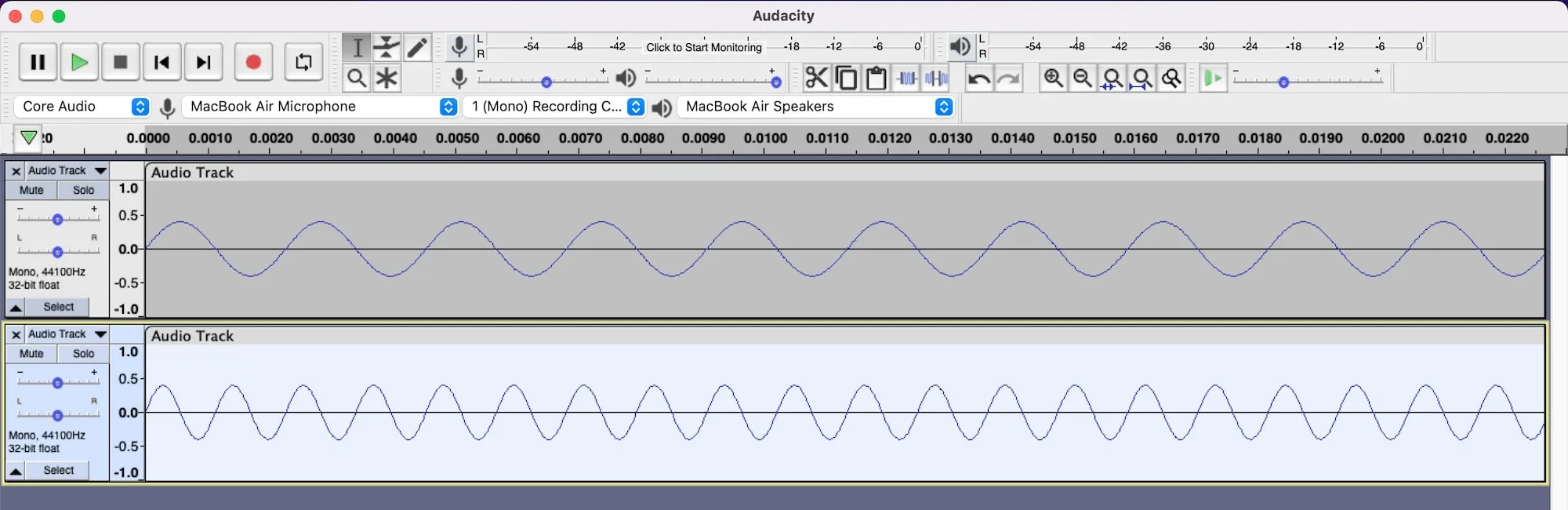

We can see additive synthesis in action with some help from Audacity.

- Let’s start off with one tone.

- Generate a 440Hz tone (Generate > Tone… > Sine).

- Play it. You’ll hear a pure tone.

- Now let’s add another tone.

- Make a new track (Tracks > Add New > Mono Track).

- Generate an 880Hz tone in the new track. Same method as above.

- Play it to hear a beautiful sounding octave.

During playback, Audacity will combine the samples from both tracks by summing them and play the summed signal.

You can try layering other frequencies (554Hz, 659Hz) to play a nifty A Major chord.

Fundamental Frequency

A side note. When combining two frequencies with additive synthesis, something subtle happens. The ground shifts and our feet fumble! The fundamental frequency implicitly changes!

DIY Example

- Fire up Audacity.

- Generate a 400Hz sine tone. (Generate > Tone...)

- Generate a 402Hz sine tone on a different track.

- Play the audio and observe. How many times does the audio peak per second?

It peaks twice per second. (That is, we implicitly added a 2Hz signal beneath!)

Specifically, the fundamental changes to the greatest common divisor (GCD) of the two frequencies.

More notes:

- When we play a note and its 5th (in Just Temperament), say 440Hz and 660Hz, our fundamental is 220Hz.

- With octaves, the fundamental frequency is just the frequency of the lower note.

- This also leads to some interesting phenomena.

- When we play two super-low-register notes a semitone apart, we get funny, dissonant pulses emanating from our keyboard or piano.

- This may also lead to unpleasant buzzes when mixing synths, possibly due to frequency modulation on top of a steady tone.

Wavetable Synthesis 🌊

In previous code blocks, we computed samples using sin(). But what if we wanted to compute something more complex? Do we really just reverse the Fourier theorem and apply additive synthesis on a bunch of sine signals? It turns out there's a better way.

A more efficient approach is to interpolate over pre-generated values, sacrificing a bit of memory for faster runtime performance. This is known as wavetable synthesis or table-lookup synthesis. The idea is to pre-generate one cycle of the wave (e.g. a sine) and store it in a lookup table. Then when generating samples for our audio, we would look up the pre-generated samples and derive intermediate values if necessary (via interpolation).

This is akin to preparing a cheat sheet for an exam, but you're only allowed to bring one sheet of paper—space is precious. You decide to only include the most crucial equations, key points, and references. Then when taking the exam you refer to the cheat sheet for ideas, connect the dots, and combine them with your thoughts to form an answer.

Example of wavetable synthesis. The blue dots (above) show a pre-generated wavetable of length 32. The red dots (below) are samples of a 8Hz sine wave sampled at 100Hz, generated by interpolating on the wavetable. (Source Code)

Wavetable synthesis can be implemented in C++ like so:

For a sine wave, we don't gain much in terms of performance. But when it comes to generating complex waveforms, wavetable synthesis rocks!2

Wavetable synthesis is commonly used by MIDI to generate sounds. Each instrument has its own soundfont, which is a collection of wavetables of different pitches. This unifies the synthesis approach for all instruments, as some may be simple to generate (e.g. clarinet) while others are more complex.

Additive synthesis and wavetable synthesis serve two very different purposes!

- Additive synthesis aims to combine multiple waveforms, of any shape and size (e.g. playing chords, or combining guitar and voice tracks).

- Wavetable synthesis aims to generate a specific waveform (in a fast manner).

Besides this software approach, we can also leverage hardware to speed up processing. But this is a matter for the next post.

Exercise for the reader:

- What variables affect the speed at which we iterate through the pre-generated wavetable?

- What happens if we try to generate a waveform with frequency equal to half the sample rate? Or with frequency equal to the sample rate itself?

Recap 🔁

Audio generation is pretty fun once we dive deep, as are its applications: toys, electronic instruments, virtual instruments, digital synths, speakers, hearing aids, and whatnot. As before, I hope we communicated on the same wavelength and the information on this post did not experience aliasing. 😏

In the next post, we'll dive even deeper into audio synthesis (particularly in embedded systems) and engineer a simple tone generator.

To recap…

- Audio samples may come from several sources. It may be recorded, loaded from a file, or synthesised.

- We can synthesise musical pitches by buffering samples and feeding them to hardware.

- According to the Fourier Theorem, all signals can be broken into a summation of sine waves.

- To combine audio signals, we can apply additive synthesis.

- This also allows us to play multiple pitches simultaneously (chords).

- We can generate complex waveforms by using wavetable synthesis, which trades memory for speed by sampling pre-generated signals.

Further Reading:

- Waveforms (Sine, Square, Triangle, Sawtooth)

- Most audio synthesis tutorials cover simple waveforms; but as internet content is saturated here, I'll just drop a couple links. I couldn't find an article I like that introduces these waveforms in all their glory. If you know of better articles, let me know.

- Perfect Circuit (conceptual, high-level)

- Electronics Tutorial (geared towards electronics; would be a nice read to prepare for the next post)

- Beginner’s Guide: Everything you need to know about synthesis in music production – Introduces more forms of audio synthesis, geared towards music production.

Footnotes

Boy, do I have a lot to say about buffers. Why is the buffer size important? Small buffers may reduce the efficacy of batching operations (which is the primary purpose of buffers). Large buffers may block the processor too much, making it sluggish to respond to new input. Choosing an appropriate buffer size also depends on your sampling rate. With a buffer size of 1024 sampling at 44100Hz, we would need to generate our samples every $\frac{1024}{44.1\text{kHz}} \approx 23.2$ ms. On a single processor, this means we have less than 23.2 ms to perform other tasks (e.g. handle UI, events, etc.). ↩︎

Guess what? There are more ways to optimise wavetable synthesis—so it'll rock even more! See the open source LEAF library for an example of optimised wavetable synthesis in C. ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.