The Mathematics of Types

Programming isn't about mindlessly typing away on a keyboard. There is an aesthetic quality that comes with approaching a problem.

Algebraic data types (ADTs) encompass a wide range of types commonly used in our day-to-day tasks. Over the past years, they’ve grown in popularity with the rise of modern languages such as Rust and Scala. They allow us to effectively model data, write readable code, and catch bugs at compile time. But rarely do we consider the aesthetics behind such constructs.

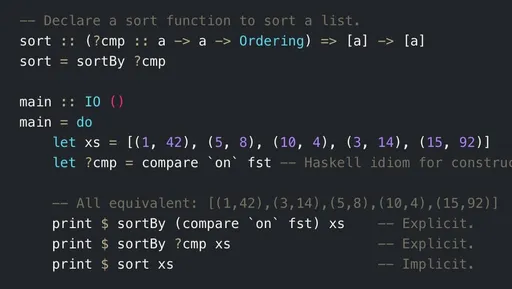

This post is for the curious programmer. Today, we’ll be looking at the mathematics behind ADTs. In doing so, we also gain an appreciation for their utility and aesthetics. I’ll be mainly using Haskell code blocks in this post, because types are very straightforward to express in this language. If you’re unfamiliar with Haskell, fear not!—the concepts addressed below are transferable to most programming languages.

Motivation for ADTs

We are interested in combining types, but that alone isn’t saying much. First, we want to combine types meaningfully in order to communicate ideas through those types. This notion lies with expressibility and the art of programming. Code is, after all, a medium between programmers.

Second, we want to combine types concisely; our types shouldn’t contain redundant, ambiguous information. Removing redundancy implies removing duplicate or invalid states, leading to better maintainability and fewer bugs.

ADTs offers us two ways to combine types: product types and sum types.

Product Types

If you’ve used structs, tuples, or record types, then you already have a sense of what product types are. Product types combine types together as one. A pizza is like a product type, combining crust, cheese, and toppings. When you bite into a pizza, you enjoy the sensation of all three together.

Here are some product types in Haskell:

In the final example above, we wrote a product type representing a Person. All people have name and age properties, so it makes sense to combine them in coexistence.

Sum Types

Sum types are another way to combine types. In contrast to product types, sum types combine types exclusively. The choice of crust is like a sum type. Should the crust be thin, thick, or stuffed with cheese? We can only choose one option.

Sum types in their simplest form are just enums. In C/C++, we might define them like so:

In Haskell, a Bool can be defined like so:

Notice the vertical bar |. This means a value with type Bool can either be False or True. It can’t be both at the same time.

Sum types also allow us to represent more complex data structures. Suppose we want to model students and teachers in a school. The traditional object-oriented method would be to declare a base Member class, then derive Student and Teacher classes.

In functional programming, we could express a Member as a sum type of Student or Teacher.

Here, Student and Teacher are two branches of the Member type, and a Member can only be either a Student or a Teacher. We can also add more branches to the sum type, such as Administrator, Visitor, and so on.1

There are pros and cons for choosing between the object-oriented approach and functional approach, but that’s a topic for another day.

Sum types also enable us to express errors in a type-safe way. We can create a Maybe type that can be either Nothing or Just with the former indicating no result, and the latter indicating some result. (More on this later!)

This type allows us to handle errors in a more structured way and avoid a lot of if-else statements (with the help of monads!).

To sum up, sum types enable us to express complex data structures, while avoiding redundancy and making our code more maintainable and type-safe.

We call Just a data constructor. This means we can construct concrete data by applying values to Just, as if it were a function. For example, Just 1, Just "in", and Just (Just 42) are all concrete data. The same applies to False, True, and Nothing, but those don’t take arguments.

Types in the Wild

Let’s familiarise ourselves with ADTs and look at a few use cases.

Product Types in the Wild

In most languages, product types are useful when passing/returning data containing multiple values. For instance, we can define a divMod function which returns the quotient and the remainder of two numbers.

In the Haskell REPL, lines starting with ghci> indicate REPL input. Other lines are REPL output.

Sum Types in the Wild

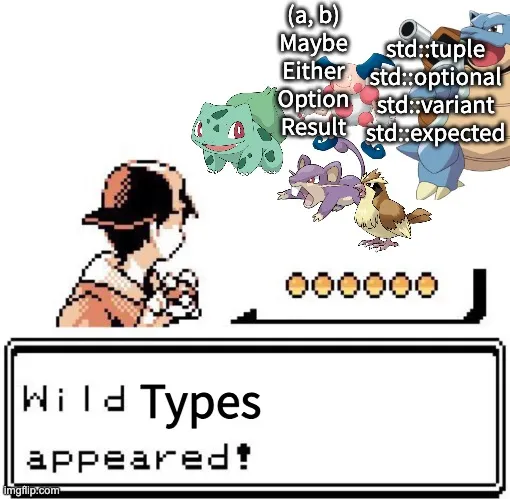

There are two common sum types in the wild: Maybe (introduced previously) and Either. These are typically used to express errors: either an error occurred or a valid result is returned.

Maybe and Either have other names as well. In Rust, they’re called Option and Result. In Scala, it’s Option (not the same one as Rust!) and Either. In C++, it’s optional and expected2. This list isn't exhaustive, but it goes to show how ubiquitous sum types are—though not as widespread as product types, for historic reasons.

Again, Maybe is defined as a sum type like so:

Here, a is a type parameter, much like the type parameters in C++ templates and other generic programming languages. We can substitute types to get a concrete type. For example, we can have Maybe Int, Maybe Bool, Maybe String, or—for the absolute masochists—Maybe (Maybe (Maybe Int))!

Maybe is commonly used to denote a computation that might fail. For instance, we can write a safe integer divide function which returns Nothing when the divisor is 0 (indicating an error, since we can't divide) and returning the wrapped quotient otherwise.

Maybe is used in other places where the error is obvious, such as in map lookup (where Nothing implies non-existence).

Either is similar, but is defined over two type parameters.

The type parameters a and b can be anything; but commonly, a is used to describe an error (such as a String or an enum) while b is some successful computation.

In the wild, Either is used in Haskell parsing libraries to return parse results. Sometimes, the parse is successful and returns the generated tree or data (Right). Other times, the parse fails and the library returns information of where it failed (Left). For example, maybe it failed to parse an unexpected : at line 5, column 42 of something.json.

The Algebra of Types

The astute may notice that product types combine types in an “and” fashion, whereas sum types do so in an “or” fashion. One of the alluring aspects of ADTs is that we can construct an algebra over them, allowing us to rigorously work with types.

In the following parts, we'll explore how types relate to math and apply algebraic principles similar to those from elementary!

A word on notation.

- Monospaced letters ($\texttt{a}$) denote types/code,

- $|\texttt{a}|$ denotes the size of set

a, - $\equiv$ denotes an isomorphism between types (as in $\texttt{Int} \equiv \texttt{Int}$), and

- $=$ is reserved for good ol' algebraic equivalence.

Types as Sets

Let’s start by treating types as sets of values.3 For instance, a Bool can be thought of as a set of two values: ${\texttt{True}, \texttt{False}}$, so $|\texttt{Bool}| = 2$.

What about a $(\texttt{Bool}, \texttt{Bool})$? Each Bool can be either True or False; thus their combination yields $|(\texttt{Bool}, \texttt{Bool})| = 2 \times 2 = 4$ values. Generalising this,

$$ |\texttt{(a, b)}| = |\texttt{a}| \times |\texttt{b}| $$

See how it got the name “product type”?

What about sum types? How many values can Maybe Bool take? In the Nothing branch, we have one value: Nothing. In the Just branch, we have two: Just True and Just False. Altogether, $|\texttt{Maybe Bool}| = 3$. In general,

$$ \begin{align*} |\texttt{Maybe a}| &= |\texttt{a}| + 1 \\ |\texttt{Either a b}| &= |\texttt{a}| + |\texttt{b}| \end{align*} $$

Indeed, product types resemble multiplication over spaces whereas sum types suggest addition over spaces.

Isomorphism of Types

The above-mentioned mathematical representation may come in handy when refactoring/optimising code.

Suppose we want a type with two “bins”: bin A and bin B. Items can belong to either bin, but not both… How can we represent this as a type?

One way is to use Either a a. We let Left x denote items in bin A, and Right x denote those in bin B.

Is there another way to represent the problem? Yes: (Bool, a). We can use the Bool to flag whether the corresponding item is in bin A. Thus, (True, x) and (False, x) are used to denote items in bin A and B respectively.

In fact, we’ve just constructed an isomorphism between types!

The beauty is in the algebra. The equivalence above can be succinctly (and abstractly!) written as $\texttt{Either a a} {} \equiv \texttt{(Bool, a)}$—or more algebraically, $a + a = 2a$.

More formally, an isomorphism exists between types a and b if we can convert between the two types without loss of information. The most straightforward approach is to define two functions: toRHS :: a -> b and toLHS :: b -> a. Alternatively with the algebra presented above, we can easily prove isomorphisms by checking the algebraic equivalence of two types!

With the toy example presented above, our converters would be

Notice how information is preserved, i.e. $\texttt{toLHS }(\texttt{toRHS } x) = x,\ \forall x \in \texttt{Either a a}$ and $\texttt{toRHS } (\texttt{toLHS }y) = y, \ \forall y \in \texttt{(Bool, a)}$.

In the same vein, the following types are also equivalent:

$$\texttt{Maybe (Maybe a)} \equiv \texttt{Either Bool a}$$

$$\texttt{Maybe} \texttt{(Either (a, a) (Bool, a))} \equiv \texttt{(Maybe a, Maybe a)}$$

Unit Values in the Algebra of Types

But wait, there’s more! There are also null and unit types which behave just like 0 and 1 in the integers, with the usual axioms.

Meet Void and (), two very special types. Void resembles the null set: it has no concrete values. So how is this type used? Well, without any concrete values, its primary utility is in the type level. For example, in the Megaparsec parsing library, Void is used in Parsec Void u a to indicate a default option.

() is the 0-tuple, the singleton set containing () itself. (To clarify, “()” is both a type and a value, depending on the context.)

C’s void should not be confused with Haskell’s Void. The former is more like (), containing only one possible result.

With these funky creatures, we can write isomorphisms such as:

$\texttt{Either Void a} \equiv \texttt{a}$

- Corresponds to $0 + a = a$.

- Bijection:

$\texttt{((), a)} \equiv \texttt{a}$

- Corresponds to $1 \times a = a$.

- Bijection:

You may verify that the bijections4 hold, i.e. show that $\texttt{toLHS }(\texttt{toRHS } x) = x$ and $\texttt{toRHS }(\texttt{toLHS } y) = y$ for any $x$ and $y$.

As for other algebraic constructions, I shall kindly leave them as an exercise for the reader. 🙃 Try coming up with examples of types and bijections for the following:

- Associativity: $(a + b) + c = a + (b + c)$, $(ab)c = a(bc)$

- Commutativity: $a + b = b + a$, $ab = ba$

- Distribution: $a(b + c) = ab + ac$

- Null: $0a = 0$

Enums as Sum Types

An aside regarding sum types and enums.

Early on I mentioned sum types as a way to combine types. Then I suggested enums as an example of sum types… But we usually think of enums as combining values, not types. What’s going on here?

Well, one way to view enums is to treat each value as if they take a unit type () parameter. That is,

(N.B. $\texttt{Bool} \equiv \texttt{Either () ()}$.)

Here, False is a data constructor while () is a type. In this version of Bool, we’re basically combining a bunch of unit types () using different tags.

In this regard, we can think of enums as sugar-coated sum types; and conversely, sum types can be thought of as glorified enums. We’ve seen how enums and sum types can be defined similarly in Haskell. The same goes for Rust and Scala 3, where the enum keyword is not only used to define enums, but also sum types (and in general, ADTs).

Conclusion and Recap

Is that all?

Au contraire.

Algebraic data types may be sufficient for most use cases, but we’ve only scratched the surface. There are more quirky animals out there! Generalised ADTs. Union/disjunctive types. Conjunctive/intersection types. Pi types.

But to recap:

- Algebraic data types (ADTs) consist of product types and sum types.

- By leveraging ADTs, we can write code that is meaningful and concise, modelling the real world more closely.

- There are two main forms of ADTs. Both enable us to combine smaller types into larger types.

- Product types can be thought of as a multiplication on types.

- Similarly, sum types are like a summation on types.

- ADTs follow mathematical laws similar to other structures (e.g. the integers), but without the inverse property. These mathematical laws allow us to rigorously reason with types.

- We can express ADTs through a mathematical algebra such as $|\texttt{(a, b)}| = a \times b$ and $|\texttt{Either a b}| = a + b$.

- Types with an equivalent algebraic representation are isomorphic. This may prove useful in refactoring and optimising.

- The algebra of types follows algebraic laws similar to the laws for integers and other algebras. There are laws on identity (e.g. $0 + a = a$), associativity, distribution, etc.

- Thus, in addition to their utilitarian use, types also exhibit an aesthetic beauty.

References/Further Reading

- The Algebra of Algebraic Data Types: Part 1 by Chris Taylor

- Type Isomorphism by Kwang Yul Seo

- The Algebra of Algebraic Data Types: Part 2 by Chris Taylor (dives into recursive ADTs!)

Footnotes

We could do the same in C++ by using Boost variant, using C++17’s

std::variant, or using a tagged union (which is just aunionwith auint8_t/inttag). ↩︎std::optionalwas introduced in C++17, andstd::expectedis expected (haha) to arrive with C++23. You can still pull these types from various libraries though. ↩︎I should mention—there are significant differences between types and sets. But please bear with me, for the sake of this post. ._. ↩︎

A bijection is also known as a one-to-one correspondence or invertible function. Each input must map to one (and only one) unique output.

Functions such as $x \mapsto \sqrt{x}$ and $x \mapsto \lfloor x \rfloor$ are not bijections since multiple inputs may map to the same output—we can't recover a unique input given an output. This is the whole idea of being invertible. ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.