Reverse Engineering a Siemens Programmable Logic Controller for Funs and Vulns (CVE-2024-54089, CVE-2024-54090 & CVE-2025-40757)

When security by obscurity breaks...

This post is a personal mirror. The canonical post can be found on the DarkLab blog.

Under the sweltering heat of the Hong Kong summer, we entered a looming building and kicked off what was supposed to be a simple penetration test. Little did we know, this ordeal would lead to panic-stricken emails, extra reports, and a few new CVEs.

This is a tale of the unexpected discovery of three CVEs in a Siemens logic controller, reverse engineering a bespoke architecture, and an authentication bypass obscured by proprietary file formats.

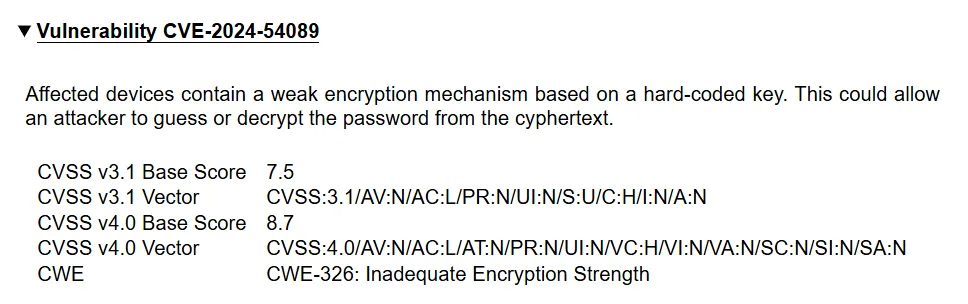

CVE-2024-54089– Weak Encryption Mechanism Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC DevicesCVE-2024-54090– Out-of-Bounds Read Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC DevicesCVE-2025-40757– Information Disclosure Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC Devices

Background

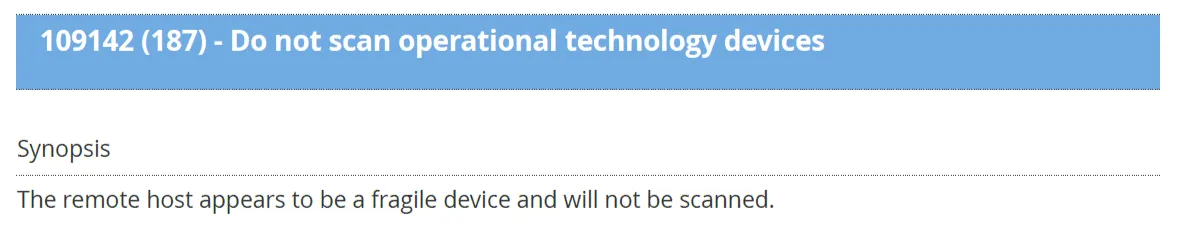

Our story begins with a simple network penetration test. The objective was to test our client’s internal network for potential vulnerabilities which could allow an attacker to take over systems from the perimeter, affect internal systems, and/or pivot to other networks. After a bit of mundane scanning and spreadsheet wrestling, we came across a few devices marked as Operational Technology (OT).

Nessus detected BACnet devices on the network.

Meet the Siemens Apogee/Talon PXC Modular: a programmable logic controller (PLC) designed to automate building controls, monitoring, and energy management. These devices are primarily used in heating, ventilation, air conditioning (HVAC) systems which may have complex requirements depending on the weather, season, and time of day.

PLCs are like the managers of a building automation system. Just as managers oversee teams, allocate resources, and report to higher ups, PLCs monitor sensor inputs, execute logic, and send alerts and telemetry back to a central system or workstation.

Corporate analogies aside, quick scans of the device revealed interesting ports: telnet, HTTP, and BACnet (UDP/47808).

Hidden in HTTP

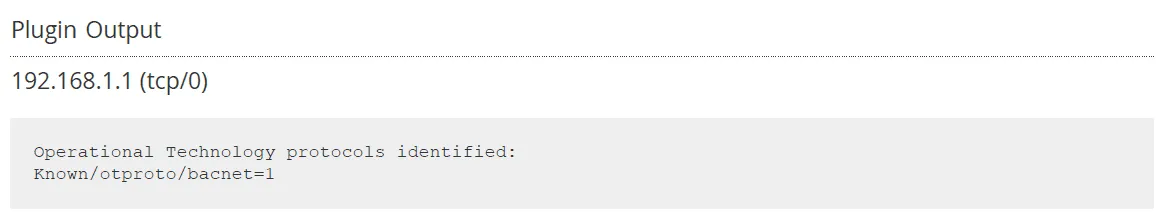

Analysis of the HTTP server quickly revealed the presence of a path traversal bug in the HTTP server, which we later validated to be CVE-2017-9947. This 7-year-old vulnerability enables remote attackers with network access to the integrated HTTP server to obtain information stored on the FAT file system.

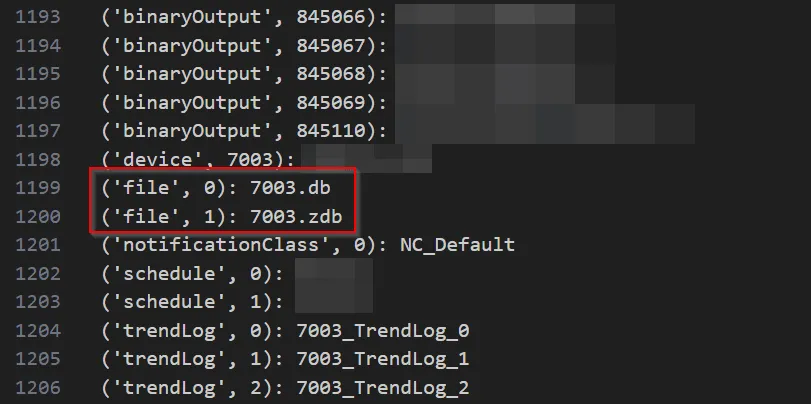

Exploitation of CVE-2017-9947 led to enumeration of the following files stored within the directory:

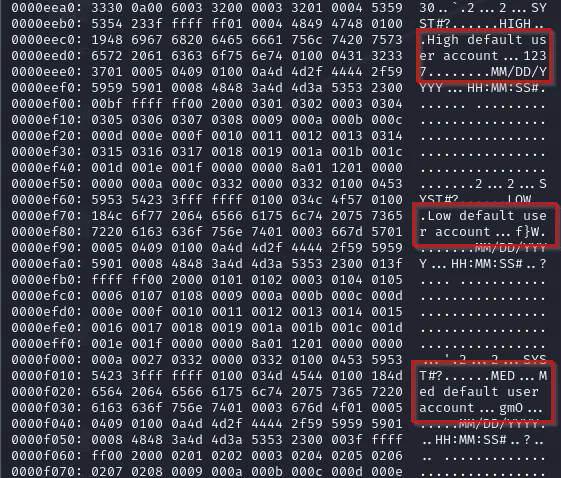

A few files piqued our interest, and we downloaded these with a special parameter. Upon opening 7002[.]db, we uncovered what appeared to be a proprietary hex format. Initially, we paid no heed to this mishmash of bytes; but later on we will discover how this information could be abused. As pentesters, time is of the essence, so we'll make a mental note and move on for now.

python custom_decode_script.py 7002.db | xxd.

Toying with Telnet

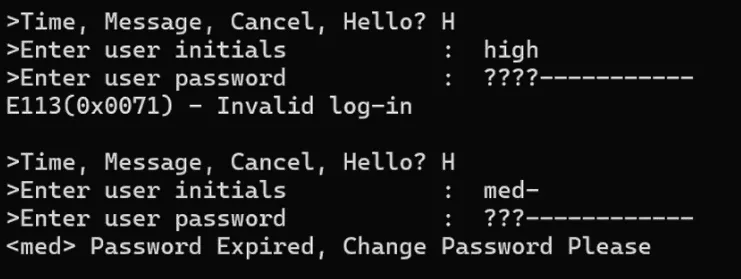

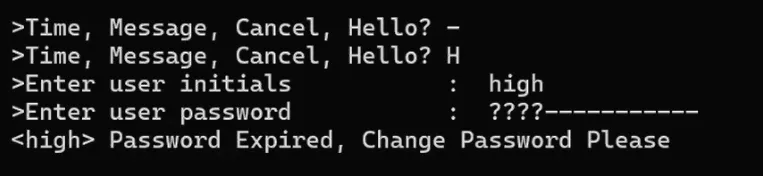

The telnet service was password-protected, but with a bit of enumeration, we identified a user manual specifying three (3) default credentials: HIGH:HIGH, MED:MED, and LOW:LOW. The first set of default credentials (HIGH:HIGH) rendered itself useless (for now), though the subsequent two sets enabled successful login to the telnet service.

We're in!

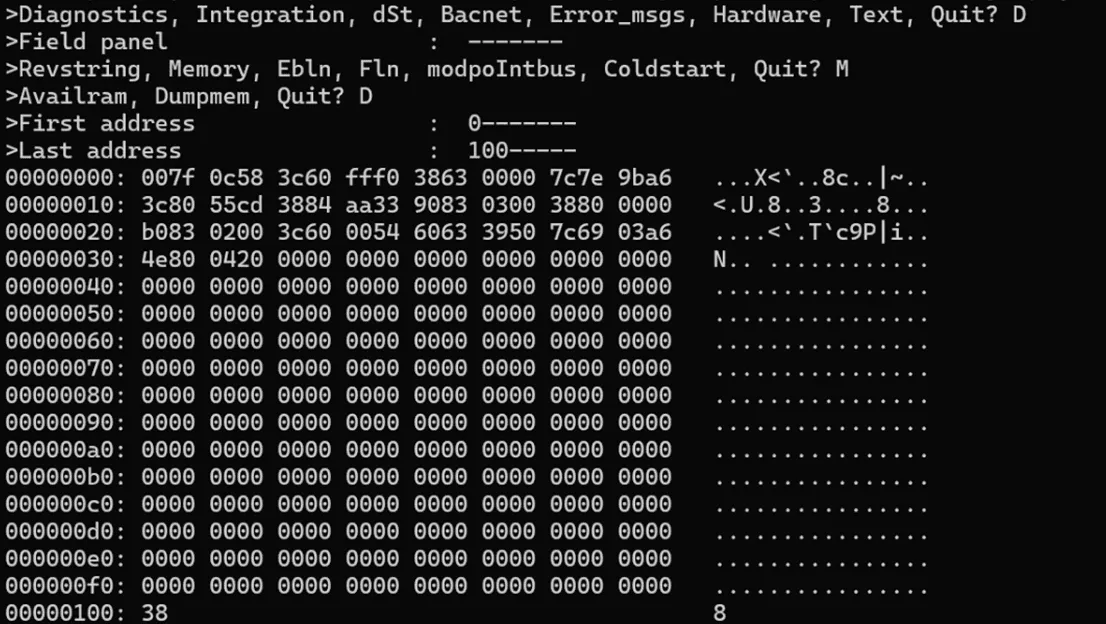

After a bit of exploration, we found we had permission to dump memory as MED!

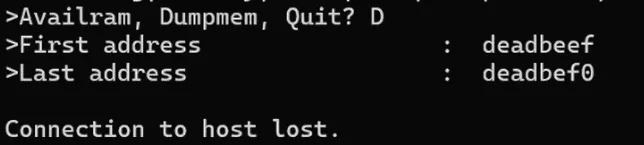

And here comes our first finding: what happens if we dump memory at a higher address?

Oh no.

Immediately, we double checked BACnet objects. Originally, over 900 objects were observed— now, only 17 remain. Needless to say, availability has gone out the window.

Current state of BACnet objects; only hardware debug information remains.

Out of curiosity, we also tried logging into telnet as HIGH with the default password. This time, it worked!

We are HIGH!

Oh no.

Let’s recap. We were initially unable to login as HIGH, but could login as MED. When we inputted a large address into the Dump Memory function, we lost the telnet connection. Further enumeration showed 99% of BACnet objects were missing, and the password for HIGH was reset.

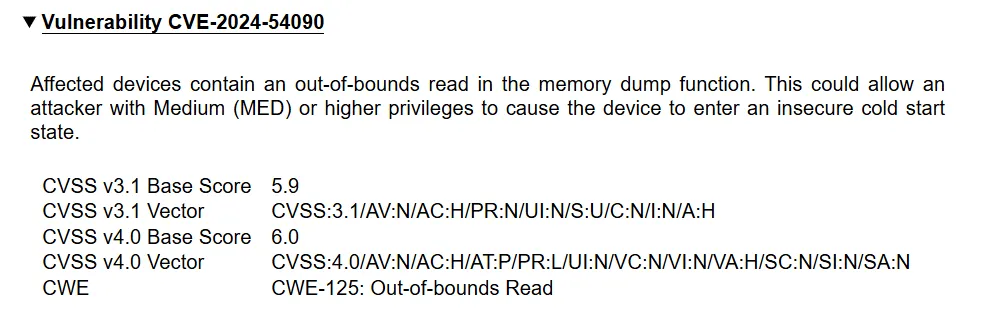

Fast forward several months, and our discovery was formally recognized as CVE-2024-54090:

A Peek at Memory and Some Deja Vu

After taking all the necessary screenshots for the first finding, we proceeded to double down on the Dump Memory function. What else could we uncover?1

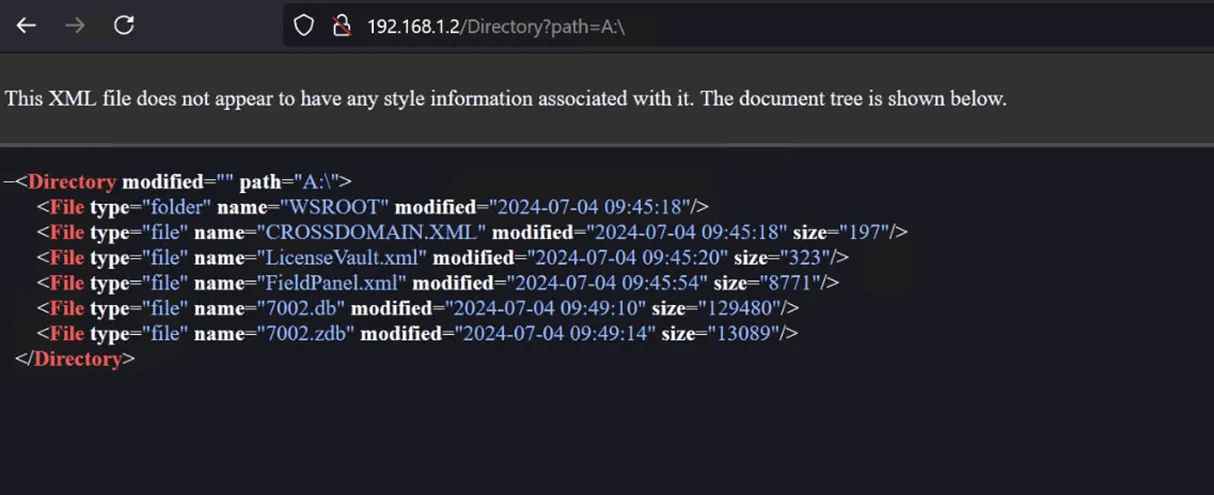

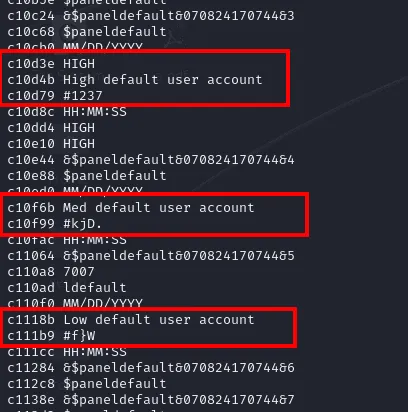

We determined the memory range to be 0 to 0x03FF'FFFF, which precisely correlates with the 64MB SDRAM listed in the Technical Spec. After obtaining the full dump, it’s time to see what’s inside! A simple strings (or od) operation revealed some familiar faces…

od -A x -S 4 dump.bin | less. The od command will attach the memory location too; quite useful when reversing alongside another tool.

Huh, curious! These are similar to the strings we previously saw in the .db file. On a whim, we tried changing our MED password and dumping the 0xc10f99 region. And sure enough, instead of #kjD., new values appeared. Not only that, but other values around the region remain unchanged, which suggests this particular memory location is tied to the password we just changed.

At this point, we hypothesised these values to be encrypted passwords. If kjD. is our password for MED, then perhaps 1237 and f}W are the passwords for HIGH and LOW respectively? After a quick test, we confirmed f}W is likely the encrypted password for LOW. So where does that leave us with 1237?

On another whim, we tried logging in as HIGH with the password 1234, and… we’re in?! (again)

WHAT?!

In utter disbelief, we toyed around with other passwords, and well— you can see the results for yourself.

| Plaintext | Ciphertext |

|---|---|

| 1234 | 1237 |

| 123456 | 123453 |

| 000000 | 000005 |

| 111 | 113 |

| 111111 | 111114 |

| aaaaaa | -FjiF- |

| bbbbbb | -EijE- |

Sample plaintext/ciphertext pairs. Notice how passwords comprised solely of digits are easily guessable.

This leads us to our second finding, CVE-2024-54089; a weak password encryption mechanism. At this point, it was confirmed an attacker could guess certain passwords.

In the next few sections, we will show how we discovered how to decrypt any password. We initially attempted to reverse the encryption with a black-box approach and tried our hands at differential cryptanalysis. After much deliberation and regret at not having played more cryptography-style CTF challenges, we decided it was time for a different approach.

Taking a Trip Down Memory Lane

To solidify the impact of our finding (and to properly crack the xor-based slop), we proceeded to reverse-engineer the memory dump.

Loading Memory

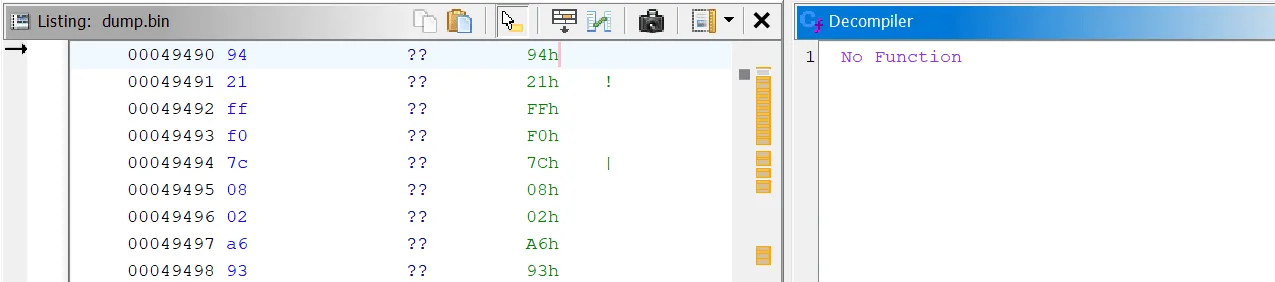

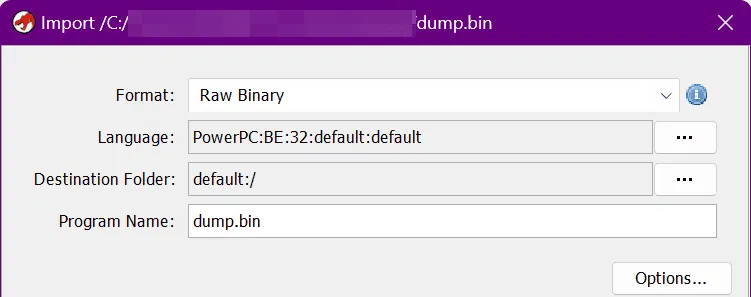

While strings and od can provide clues, they do so without much context. We loaded the entire 64MB memory dump into Ghidra and were greeted with this marvellous junk:

Oops, wrong endian. Let’s try loading the same file with big endian instead.

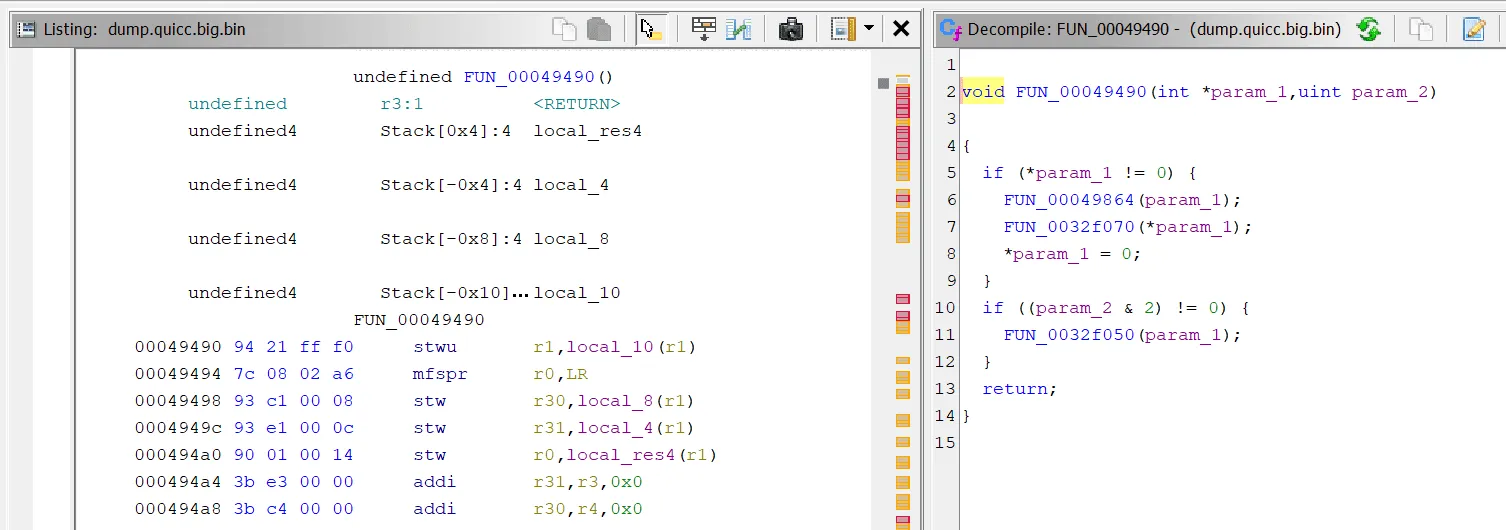

That’s more like it!

PowerPC supports both big and little endian, which determine the order of bytes being interpreted. If we specify the wrong endian, the disassembler cannot correctly parse instructions. Apparently, this particular PLC uses big endian.

From here, we can hunt for more vulnerabilities or dig deeper into our previous findings. For now, we’ll stick to reverse engineering the encryption algorithm. But where do we start?

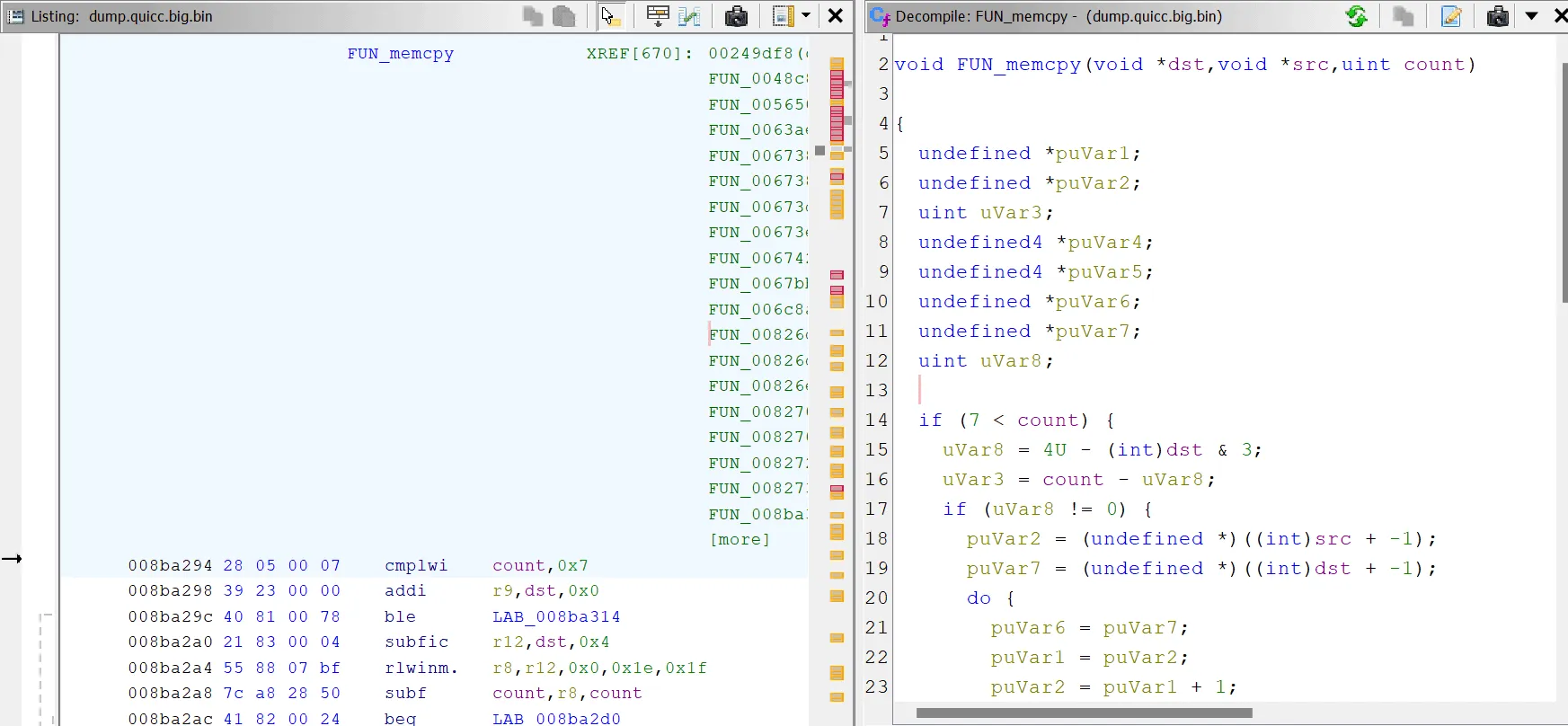

libc: An Exercise in Reverse Engineering

Without symbols, standard C functions are expressed as mumbo jumbo. While these are tedious to reverse, it does help stretch our reversing brains a bit. For instance, the following function has over 600 cross-references (XREFs). If we can identify this function, we’ll have an easier time reversing other parts of code. What do you think this function is?

This is indeed memcpy. This copies param3-bytes from the memory at param2 to the memory at param1. The actual decompiled function is slightly more complicated with optimisations for copying the buffer by words (4 bytes) instead of byte-by-byte. To make our lives easier, we’ll edit the function signature with the appropriate names and types.

Here’s another function (over 1200 XREFs). What could this be?

Hint: What is being returned and how is it computed?

Some lines might seem scary, but let’s work with what we observe and know:

param_1operates on achar*and the null byte\0is checked, so this is likely a string operation.- The return statement

pcVar3 - 1 - param_1is a good clue that the function is doing some index-of or counting operation sinceparam_1is the start of the string. Analysing the code, no other special operation is performed aside from incrementingpcVar3andpcVar4. - Hence, ignoring the weird constants in the nested while-loop, we can conclude with relative certainty that this is our good friend

strlen. - For the curious, the

uVar5 + 0xfefefeff & ~uVar5 & 0x80808080magic is some bitwise trickery to check for null bytes in a word.

We continued hacking away at familiar functions before slowly moving on to complex higher level functions.

A Note on RTOS

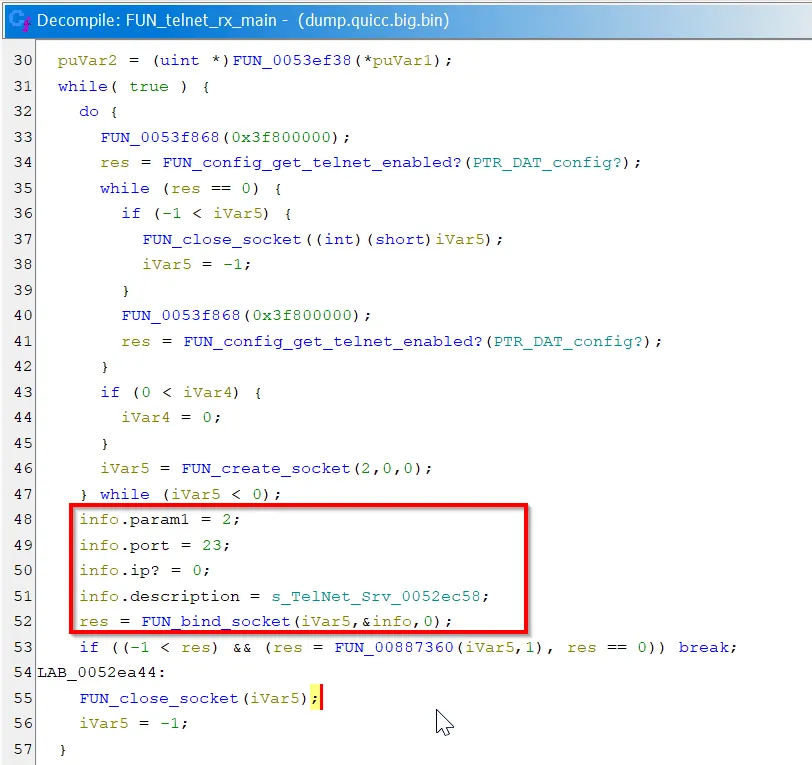

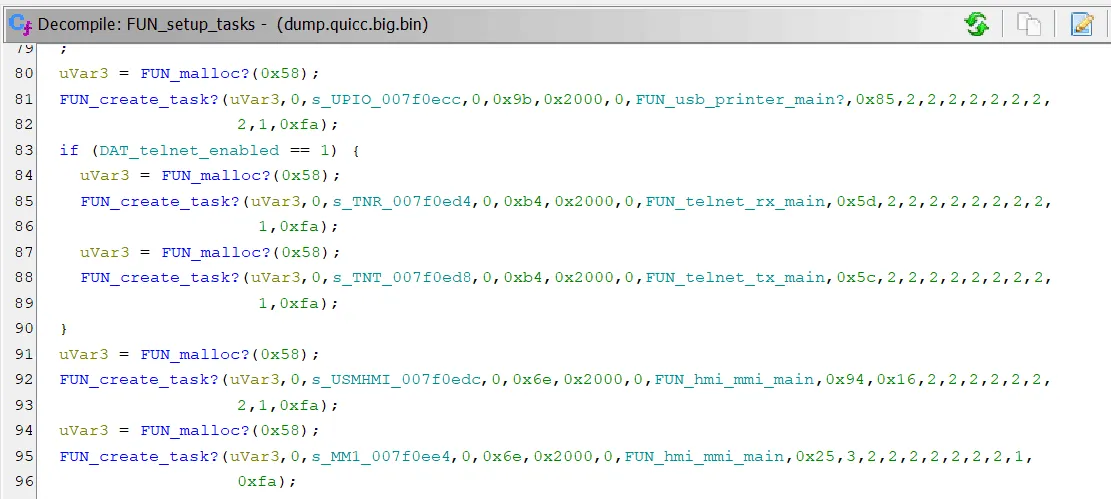

We tried finding the encryption function through different approaches. While noodling around, we came across the thread function running the telnet server (think: the main function / entrypoint of the thread). We were unable to proceed in drilling down to our target (shakes fist— curse you indirection!), but this still posed a good opportunity to observe how the PLC works at the embedded level, and to revisit concepts of embedded software.

By correlating strings and the number 23 (the default telnet port), we determined functions relevant to socket programming.

For a bare metal system to handle multithreading, a common approach is to use an RTOS (Real-Time Operating System). The RTOS is often provided as a library/API containing threading and synchronisation primitives. It is also common to allocate space for a stack then call some create_task function with a function pointer to the entrypoint of the thread.

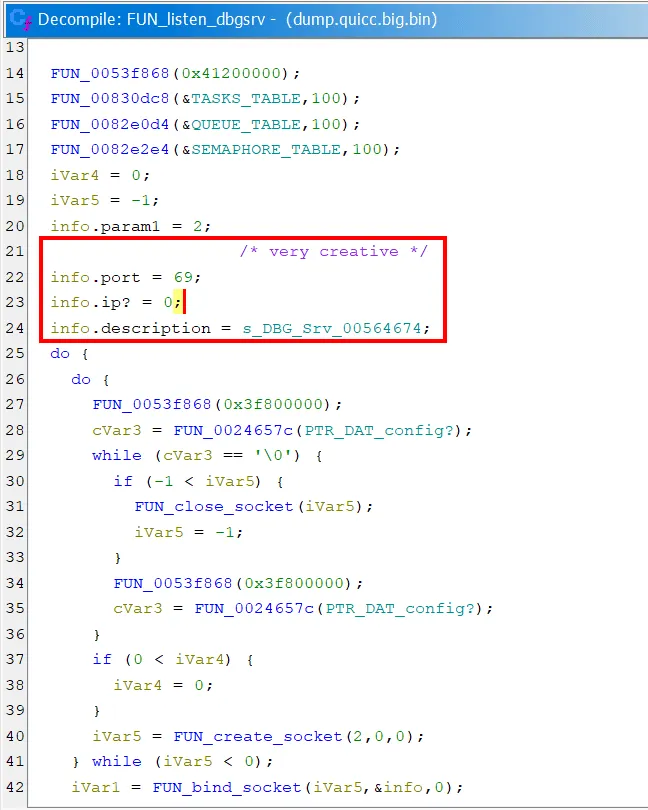

Once in a while, we come across interesting bits and pieces. As a side quest, we took a peek at the other thread functions, and uncovered the code for a debug server with a peculiar choice of port…

Our nmap scans did not reveal this port, so it is likely an artefact from internal testing. Still an interesting find though!

Uncovering the Encryption

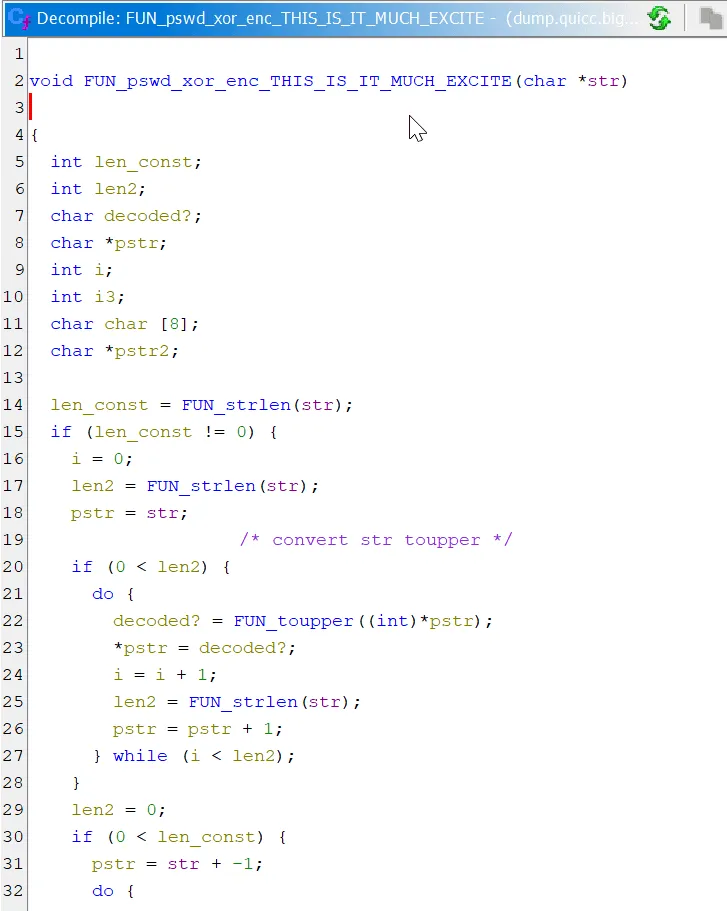

After much trial and error, we were able to find the encryption function.

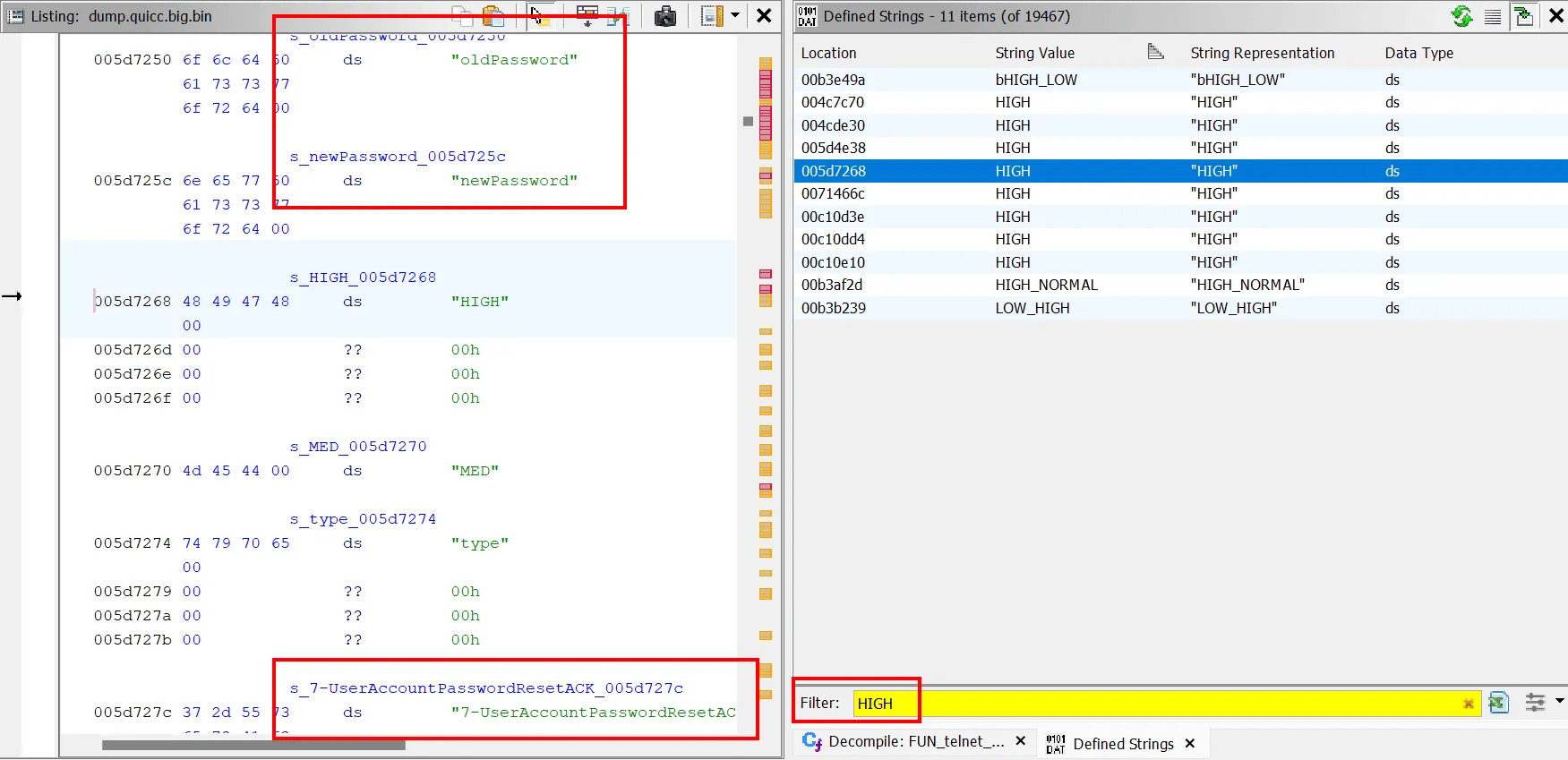

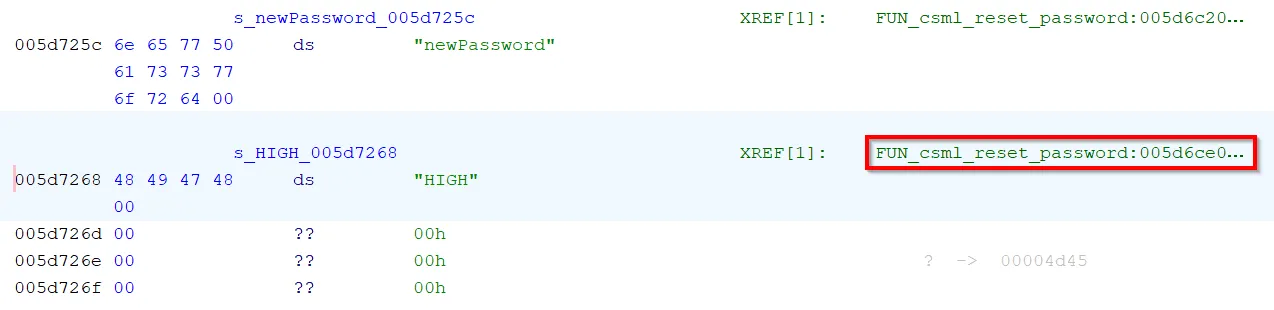

We started by again, searching for common phrases associated with login. This time we tried searching for one of the default users: HIGH. In one instance, the string was embedded among other strings such as "newPassword", "oldPassword", and "UserAccountPasswordReset" which suggests some kind of password-related activity.

We followed XREFs to a relevant function and got our hands dirty.

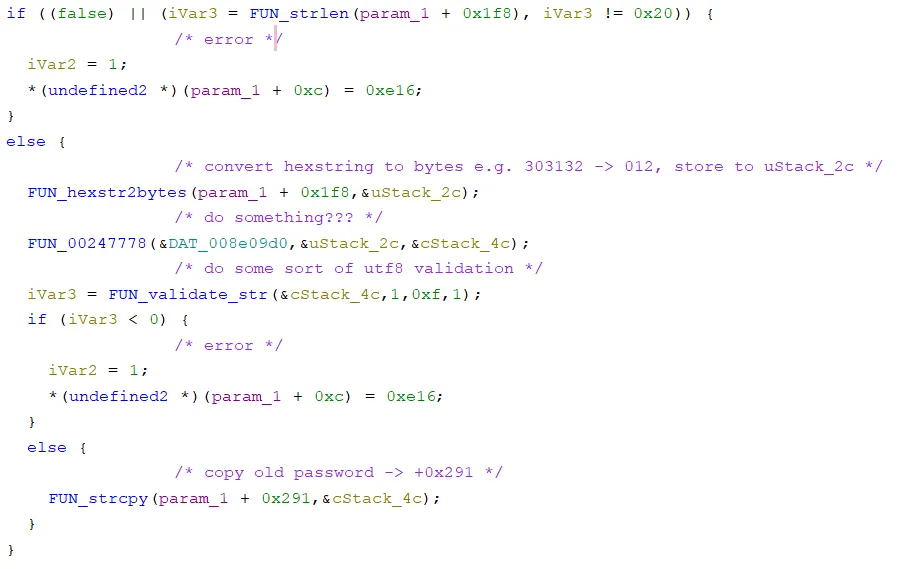

Inside the reset_password function, we identified two similar code flows which operate on the old password and new password. In the screenshot below, the old password is converted to bytes and validated before being copied into the buffer at param_1 + 0x291. Later on, the same process is applied to the new password which is copied to param_1 + 0x17a.

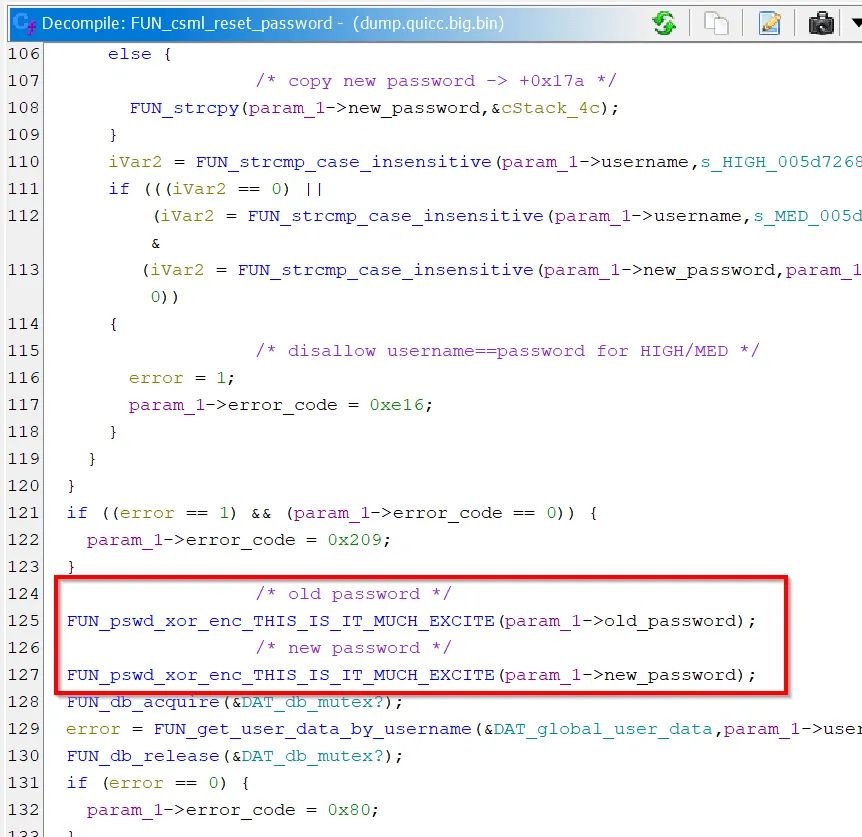

As suspected, the code eventually calls a function on each buffer, which we confirmed performs in-place encryption— the very thing we were looking for!

The actual encryption process is rather straightforward to reverse. First, the password is converted to UPPERCASE.

It then performs multiple xor operations on the string, looping through each character. Each byte is xored with a variety of numbers. And interestingly, byte 0x2a (42) shows up multiple times. Coincidence?

Once we know the encryption process, it was trivial to reverse the decryption due to the use of xor.

For security reasons, we will not disclose the full algorithm here, but the gist is that we confirmed the algorithm is xor-based with a hard-coded key. An attacker with knowledge of the algorithm can decrypt any encrypted password on any affected device.

BAC(net) to the Future

This writeup would not be complete without a juicy OT attack. After reporting the first two vulnerabilities, we realised there was an obscure information leak hiding in plain sight…

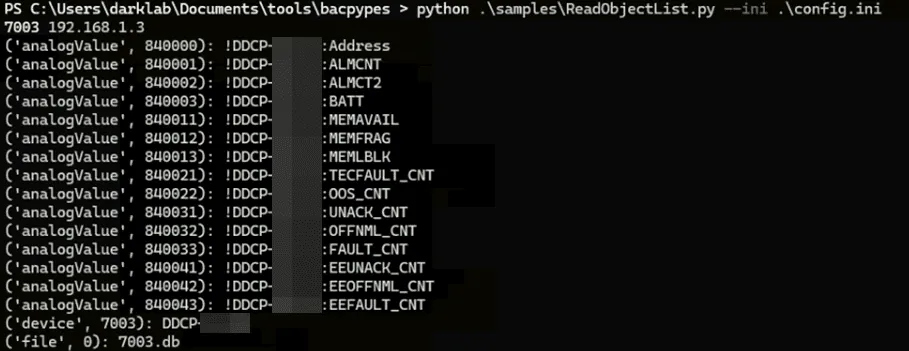

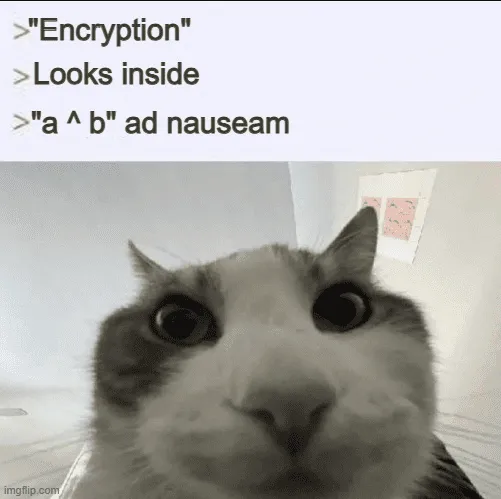

BACnet is a building automation protocol which exposes an API to read/modify settings of a device. It typically runs on UDP/47808 (0xBAC0) and is designed for lightweight and flexible communication between building controllers. We used JoelBender’s bacpypes Python library to interface with BACnet. (Check out The Language of BACnet to learn more about BACnet basics.)

BACnet objects found by querying with bacpypes.

We followed this process when enumerating BACnet:

- Gather the Device ID. (nmap, Nessus, port scan)

- List objects on the device: ./samples/ReadObjectList.py

- Select objects and list properties: ./samples/ReadAllProperties.py

From here, we tested individual properties for read/write capability. Suffice to say, BACnet network security hardly meets modern standards, but that is not our focus for this post.

Instead, we turn our attention to a few interesting BACnet objects specific to our targets:

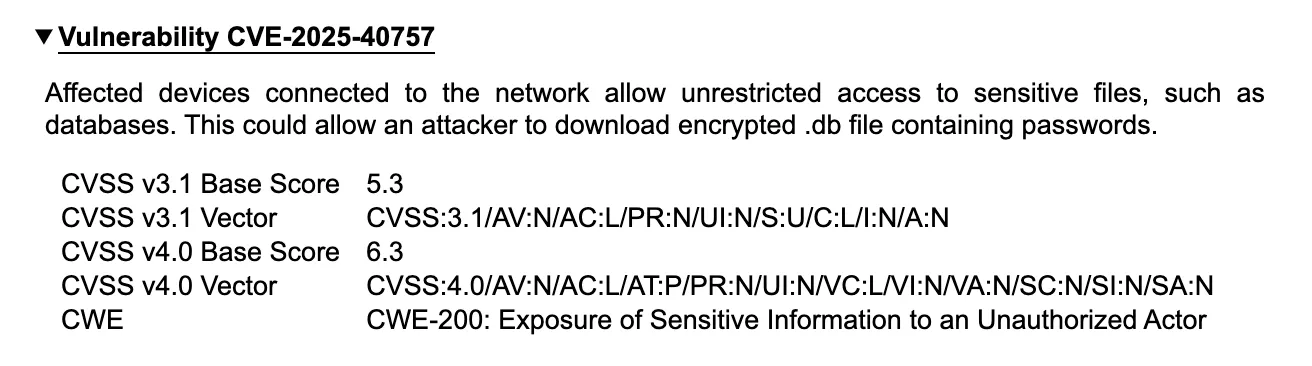

Look familiar? Using a modified version of bacpypes’ ReadWriteFile.py, we downloaded the files over BACnet. And surprise surprise— it holds the same contents as the .db found earlier in the HTTP server. But as we realised before, these files actually contain encrypted passwords; and since BACnet by nature does not have authentication, this means devices are susceptible to unauthenticated information disclosure. Anybody on the network can slurp out encrypted passwords. Alas, meet CVE-2025-40757:

The implications are huge! An attacker on the network could perform an authentication bypass by chaining the above issues: read the encrypted password from BACnet, decrypt/guess the plaintext, and login to telnet as a HIGH (admin) user. Even if telnet were disabled, the passwords could be used for spraying across other systems.

Once an attacker can login as HIGH, they could (conceptually) execute arbitrary assembly instructions with the built-in Write Memory feature or modify the embedded HTML to include an XSS snippet! More concerningly, they could compromise availability by tampering with device settings.

If anything, this goes to show how security by obscurity is insufficient.

Let’s Recap

TLDR:

- We discovered MED/HIGH users can cause the affected device to enter a cold-start state, severely impacting availability. (

CVE-2024-54090) - We reverse-engineered the encryption mechanism for telnet passwords and confirmed it was xor-based. No encrypted passwords are safe. Moreover, if a password contains only digits, it is easily guessable in its encrypted form. Decryption works across affected devices due to a hard-coded key. (

CVE-2024-54089) - We discovered an Information Disclosure vulnerability where encrypted passwords are disclosed over a BACnet file object. (

CVE-2025-40757) - By chaining

CVE-2025-40757andCVE-2024-54089, we can perform an authentication bypass, allowing one to login as any user and tamper with the device.

Mitigations

Affected Devices:

- Siemens APOGEE PXC Series (all versions)

- Siemens TALON TC Series (all versions)

As of writing, no fix is planned by Siemens. The following mitigations and temporary workarounds can be applied instead:

- Disable telnet. According to Siemens, telnet should be disabled by default, but in our experience, it is not uncommon for site administrators to enable it for convenience. We recommend disabling telnet to mitigate these vulnerabilities.

- Change the default password for all accounts (HIGH, MED, LOW) even if unused. Choose strong passwords containing a mix of letters and digits.

- Do not choose passwords comprised solely of digits.

- Note that this does not prevent attackers with knowledge of the encryption algorithm from decrypting the passwords.

- Avoid password reuse. Do not use the same passwords as your workstations and other models.

- Apply detective controls such as network monitoring to identify suspicious traffic.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Siemens ProductCERT team for coordinated disclosure. For more information on these vulnerabilities, please read the advisories published by Siemens.

CVE-2024-54089– Weak Encryption Mechanism Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC DevicesCVE-2024-54090– Out-of-Bounds Read Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC DevicesCVE-2025-40757– Information Disclosure Vulnerability in Siemens Apogee PXC and Talon TC Devices

Footnotes

It is important to caveat that we did not have the firmware for this controller, nor was Ghidra MCP available at the time, so our testing was very much black box. Further, we faced several roadblocks: 1) All symbols, libc or otherwise, needed to be reversed manually. 2) Ghidra flow detection is a bit buggy with PowerPC. 3) Code may be incomplete, since it may be overwritten with data or loaded dynamically.

Any function/variable names you see in our reversing process are a best guess based on limited information and patterns. In hindsight, our testers recognized there could have been alternative approaches taken, such as grabbing an appropriate libc.so and applying offsets, or reading up on prior research on Nucleus RTOS (which seems to be the underlying RTOS). ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.