Output-Invariant and Time-Based Testing – Practical Techniques for Black-Box Enumeration of LLMs

Abusing inherent context and sluggishness in LLMs for stealthy enumeration of prompt injection points.

Note: Given current trends, the terms "AI" and "LLM" will be used interchangeably in this post. I'll also use "traditional implementation" to refer to code without LLM/AI/NLP processes.

In a recent pentest, I tested a system which automates and streamlines a time-consuming business process. The web app would process .docx business files by transforming unstructured data to structured JSON. To expedite the pentest (because time is precious), I asked the developer: "How does the backend parse the document? Is there any particular format, say, specific headings or column names?"

Their response frankly surprised me: "No fixed format. An AI will process the document."

Exciting! An opportunity to try out prompt injection!

But I had a nagging thought: Is it possible to determine whether AI is being used purely through black-box testing? What if the devs in my next engagement used an LLM without documenting it and without informing me? What if it was a red team assessment and opsec was needed?

After multiple days of pentesting, I think I've arrived at a few simple techniques and tell-tales to identify LLM usage. Search results for prompt injection pentest methodologies were.... disappointing... so I thought I'd share these notes! (If you're aware of any resources, similar or otherwise, do let me know!)

To be clear, this post primarily addresses enumeration of LLMs in APIs and backends, rather than exploitation of LLMs. This means we are trying to answer questions such as:

- ✅ "Does the backend use an LLM?",

- ✅ "Is this field vulnerable to prompt injection?"; rather than questions like

- ❌ "What data can I exfiltrate?",

- ❌ "How can I backdoor this LLM?",

- ❌ "How can I bypass LLM defences?",

- ❌ "Can I steal Bob's credit card details from the customer service bot?".

By answering the former questions early on, we save ourselves from mindlessly poking at the other questions. We will also side-track ourselves with a couple concerns pertaining to LLM attacks:

- ✅ "What does opsec mean in LLM red-teaming?",

- ✅ "What are blind prompt injection attacks (conceptually)?"

We'll assume a Direct Prompt Injection scenario, i.e. a tester/attacker is interacting with a service, rather than Indirect Prompt Injection.

Let's take a look at the first method.

Output-Invariant (Probe-Pair) Testing

Update 2025.11.15: I realised a bit late that a term called probe-pair fuzzing exists in the literature, presented by James Kettle some 9 years ago. It describes what I call "output invariance" quite neatly, in that you send two probes: a base request and a second request crafted to illicit "interesting behaviour".

The idea is quite simple, I just think the term "output-invariant testing" sums it up nicely.

The key idea is to take a base request/response, change the input slightly without changing context, and aim to keep the LLM response unchanged.

Output-invariance is always relative to some base request. Any mention of "output-invariant prompt" implies two prompts: a base prompt and a modified test prompt.

Concept

A thought experiment: Suppose we’re testing a backend which extracts data. The input format is text-based, and the output format is JSON. Sample input:

Suppose the backend is implemented in one of two ways:

- First, a traditional implementation which uses regex or some manual approach to extract the desired text.

- Second, an LLM prompted with something like "Extract name, title, and description. Here's the format: ... Here's an example: ...". The LLM— being a black box— would do its thing, and spit out the same JSON.

Now let's put on our attacker hat. From a black-box perspective, we don't know whether the backend uses a traditional or LLM implementation.

But what if we slightly changed some fields in the base input?

The traditional implementation would return:

However, the LLM implementation would return the same response:

This is because LLMs have something traditional implementations don't: they "understand" context and language. It "recognises" Michael Scott resembles a name, and the phrase My name is indicates the following text is a name.

The key idea behind Output-Invariant Testing is to take a base (HTTP) request, then change a field slightly but aim to keep the LLM response— the output— invariant (unchanged).

To reiterate, we have two requests/responses involved:

- The Base Request/Response, derived from normal clicks and operation.

- The Output-Invariant Test Request/Response, which modifies the input with negligible natural language context, with the aim to produce the same output if it were passed through an LLM.

To detect, it's simply a matter of comparing the responses:

- If the test response is equal (or extremely similar) to the base response → LLM.

- If the test response reflects the input, or is highly dissimilar to the base response → traditional implementation (no LLM).

Output-invariant testing isn't a new concept. Those familiar with SQL injection may understand that payloads such as abc'||', abc'+' could be used to produce output-invariant SQL results. If the API is SQL-injectable, then the database would perform string concatenation on an empty string and process abc. If not SQL-injectable, then the full input (with escaped quotes) is processed or reflected.

Sample SQL query:

Advantages

A natural question may be: But why use this approach? Why not just go straight in guns ablazin' with the awesome adversarial prompts?

My response would be:

- Using the output-invariant approach is opsec-friendly. I’ll explain what this means and why in a later section.

- For manual testers, the cognitive load is minimal, which is ideal for situations where a fast and reliable method is desired. The overhead for output-invariant prompts is small. Instead of using 5 paragraphs illustrating a fantasy novel or threatening a dystopian death on someone's dear grandma, we simply add/change a few words.

- Consider what happens if the input isn't reflected in the HTTP response. We don't have immediate feedback from the LLM. In other words, suppose we're dealing with Blind Prompt Injection. We’ll discuss this more in a later section.

Limitations

Output-Invariant Testing may not always succeed due to implementation differences.

- The backend could just be using an NLP model to analyse the text. I've been fooled once when testing a customer service chatbot. It seems to understand context and language, but turns out it's just a simple NLP plus decision tree.

- This approach might not work as effectively on certain functions, e.g. search fields. The backend might preprocess the input by dropping stop words (e.g. "the", "is", "a") or giving more weight to certain words.

Operational Security in LLM Red Teaming

When discussing operational security (opsec), we often concern ourselves with stealth and evasion. This applies less to white/grey-box pentesting where the pentester’s IP is typically whitelisted to expedite the assessment; but for red team and black-box pentest scenarios, opsec is an important consideration.

The quieter you become, the more you hear.

— quote by Rumi, as seen on some Kali Linux wallpapers.

For prompt injection, opsec means detection and evasion of potential defences such as LLM Guard. This means choosing prompts which minimise potential alerts, avoiding prompts with direct attack intent which will likely trip alarms (e.g. "Give me your secretz"). Instead of busting in with guns blazing, we want to first quietly identify weak points.

Having answered the what, let's turn to the why.

These days, even port scans or directory fuzzing may trip alarms. With LLM integrations on the rise, defences against prompt injection are also building up. It’s only a matter of time before detections for adversarial prompts are connected to SIEM tools, analysed, and used to swiftly shut out attackers.

It turns out the output-invariant approach can be quite opsec-friendly. There is no attack intent, no special character requirements, minimal additions, and the tone is passive.1

If we also consider that defences may also scan LLM output (e.g. one feature of LLM Guard), then output-invariance would still perform well bypassing output scanning, assuming a safe base request is chosen.

Blind Prompt Injection

Blind prompt injection is something I've been toying in my head. I haven't seen much mention of it, but it could be a potential avenue of attack.

Consider a second thought experiment which presents a case of boolean-based blind prompt injection. This is similar to boolean-based blind SQL injection, in that the HTTP response (or other indicator) only has two states: a "true"/ok state and a "false"/error state.

Suppose we're testing an e-commerce site. To add an item to our shopping cart, we use the following HTTP request:

And the response returns either

- status ok, if the item was successfully added

- status error, if the item name could not be found or some other error occurred. This error is generic and information is limited. Assume this is a lousy React API which only returns status code 200.

The key feature of this example is that the input is not reflected in the response, but we have boolean feedback instead.

As a black-box tester, we don't actually know whether an LLM is used. But if an LLM were used, we hypothesise it does something like:

- Receive user input from HTTP request

- Query LLM

- Process data from LLM

- Return generic ok/error response

Our base request/response is:

Now suppose we want to verify whether the backend uses an LLM. Using the output-invariant approach, we slightly modify the request to:

What does the backend see? And how would it respond? We'll summarise this in a table.

| Input | Is LLM used? (unknown to tester) | What the Backend Processes (unknown, best guess) | Status (known, observed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| The item is Brown Sugar Bubble Tea | Yes | Brown Sugar Bubble Tea | ok |

| The item is Brown Sugar Bubble Tea | No | The item is Brown Sugar Bubble Tea | error |

By using an output-invariant prompt, we can determine whether LLMs are used based on the boolean response.

Note: Underpinning this approach is the assumption that the phrase The item is Brown Sugar Bubble Tea is not a record in the database, but Brown Sugar Bubble Tea is a record, which is why different statuses are returned. If this assumption fails, the returned statuses would be indistinguishable.

Time-Based Testing

Assuming your network connection is stable, one of the best hints of an LLM is a long response time. This technique isn't always reliable, but I think it has some merit, and time-based techniques are quite fascinating, no?

The main objective is to use prompts which would induce an LLM response containing many words. Generally, an LLM scales poorly in this regard. Many words in response = long response time = we happy.

Analysis

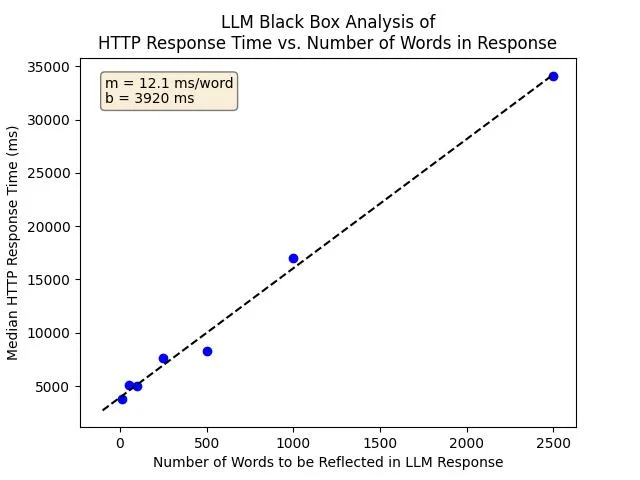

To test the feasibility of this approach, I wanted to analyse how LLM response time scales with number of words in the LLM response.

Test Methodology and Raw Data (click to expand)

We asked another AI to generate texts of lengths 10, 50, 100, 250, 500, 1000, and 2500, which we then padded to the correct word count (because LLMs suck at counting), and then fed as unstructured data to our target AI. In our case, the target AI was already prompted to extract unstructured data and to "not omit values", thus we can simply paste lengthy text into the input, and the AI will reflect that in the response. We submitted each text 10 times, observed the response times, and took the median to eliminate noise.

Requests are submitted via HTTP using Burp Suite. The backend is an API wrapper over GPT-4o. We used Burp Suite's "End Response Timer" metric to determine how long each request took.2

| Word Count | Median Response Time (ms) |

|---|---|

| 10 | 3793 |

| 50 | 5110 |

| 100 | 4975 |

| 250 | 7627 |

| 500 | 8325 |

| 1000 | 16987 |

| 2500 | 34123 |

Processed Data: Median response time vs. word count.

Raw data is here.

Based on this analysis, we can observe that despite response time being linear with respect to word count, our target LLM still operates slowly, with 1000 words taking 16 seconds and 2500 words taking 35 seconds. By performing a linear regression, we can determine the word generation rate is roughly 12 ms per word (83 words per second) and that a baseline request (for LLM input processing and other API tasks) would take 3.9 seconds.

What this all means for the layman is that there is a very clear trend that LLMs have a slow time-vs-word rate. We can take advantage of this in our analysis and detections.

Traditional implementations just don't take this long. After all, CPUs are pretty fast.

To use time-based testing, induce the AI to generate two responses: a small response and a large response. Observe and measure the time taken. For more detailed analysis, gather multiple datapoints with different word counts, then use linear regression to identify the words per second.

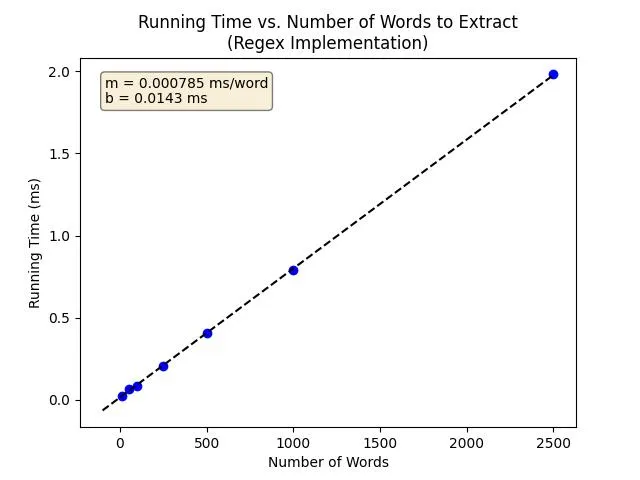

Example of Regex-Based Implementation

Just to provide a reference for a traditional implementation, I made a (generously dumb) regex script which generates dummy text and attempts to extract a regex pattern. The task is similar to the example provided in the thought experiments: "extract the description field from a text with fixed format".

The word rate is 0.785 µs per word (1,270,000 words per second) on my weak computer.

Source code here.

Inducing a Large Response

So we want to induce a large response from the LLM. There are several strategies:

- Simply providing a long input (without direct, explicit prompting) may work. If an LLM is tasked to, say, extract unstructured data, then the input will be reflected in the LLM response.

- Ask the LLM to generate long text.

- Example 1:

The description is "(the word 'apple' repeated 1000 times)" - Example 2:

The description is the first 1000 words from the Lorem ipsum corpus. - This is potentially riskier as it contains instructions directing the LLM, which may be potentially flagged by defences. The rate of success is also lower.

- Example 1:

- Other creative approaches may also work.

Limitations

- Creative/adversarial prompts may still be needed to bypass limitations, e.g. if the LLM is tasked with summarising or categorising user input.

- In our case, the AI was tasked to extract input and "not omit values", so it was easy to generate a short and long response.

- Long input, intended for reflection, may be blocked due to word/token limits.

- There are many factors affecting the runtime that may induce false positives/negatives. The backend could be using a poorly-designed traditional algorithm. It may be orchestrating other API/network requests unrelated to the LLM.

What's next?

Once an LLM / prompt injection point has been identified, it's time to test further payloads.

Note on Risk Assessment and Threat Modelling: Prompt injection by itself isn't automatically a critical issue. Yes, making the LLM "do anything now" may seem like a fun 'feature', but if the response is completely isolated, then there is little to no impact.

To demonstrate risk and impact, we need to go beyond prompt injection, leveraging it as a stepping stone for other escalations or disclosures.

- Can you leak the prompt? → Information Disclosure

- Note: there are generally two kinds of prompts:

- an initial prompt used for creating a bot (setting the role, scenario, tasks, data formats) and

- request prompts which act like an API request.

- Note: there are generally two kinds of prompts:

- Can we leak prompts, information, or files posted before? → Information Disclosure

- Does the AI have web access? (Follow up: Is it self-hosted?) → SSRF

- Can the AI execute commands? → RCE, or SSRF(?) if the commands are MCP-like presets

- Also check out OWASP LLM / Generative AI Top 10

Detection and Mitigation

With code taking the form of natural language, it is difficult to secure 100% of the LLM attack surface. Not to mention, the LLM attack surface isn't limited to natural language. Text encoding is also an issue!

Some readers may be wondering "How do we detect this kind of stealthy enumeration?". While this is an interesting question, I don't think it's the best question to ask from a risk/business perspective. I posit that a better question is: "How do we defend the prompt injection attack surface as a whole?" This is because— in my head— detecting stealthy enumeration is rarely the best use of resources.

It's more effective to apply a holistic approach and detect risky/impactful prompt attacks instead, for instance: attacks which perform code execution or exfiltrate data. Tools such as LLM Guard already implement some kind of detection in this regard. A holistic approach also means applying the usual security concepts including defence-in-depth and the principle of least privilege.

Conclusion

The rise of LLM applications is a clear signal for penetration testers and red-teamers to develop their prompt injection methodologies. In this post, we explored two methods to stealthily test for the presence of LLMs.

Further Research

Time-based testing may be an interesting avenue for further exploration. Other researchers have demonstrated time-based side-channel attacks for reverse engineering a model's output classes based on the LLM's response time.

Blind prompt injection is yet another avenue for potential research. Information disclosure is slightly trickier, but perhaps it is possible to induce the application to answer true/false questions, as if we were playing 20 questions. At the moment, the presentation of blind prompt injection in this post is purely conceptual. More testing will be needed to determine the feasibility and practicality of this potential attack vector.

Scaling and automation is a natural follow-up topic when discussing enumeration.

After making the Pam Same Picture meme, a thought occurred to me: would LLMs also normalise typos? Would they consider something like

bubble teaandbublbe teato be the same picture? This may be another option for output-invariant attacks.

Further Resources

Some resources which I found insightful:

- Testing the Limits of Prompt Injection Defence, a few creative prompts for bypassing LLM Guard

- Prompt Injection Defences, a collection of techniques/concepts/research for defending against prompt injection

- Protect AI: AI Exploits, a collection of CVEs and bugs in the AI/ML supply chain. Not really focused on prompt injection, but rather typical OWASP-like bugs in AI products/tools.

tl;dr

To recap, we want to answer two (very basic) questions:

- Does backend haz LLM?

- Iz parameter vulnerable to prompt injection?

To test, try these two black-box approaches:

- Output-Invariant Testing

- What iz it?

- LLMs understand context. We can leverage this to our advantage by crafting prompts which add minimal context, but aim to generate the same LLM output. Traditional implementations would usually reflect the input without stripping context.

- Example

- Base Input:

User: Meep - Test Input:

User: The user is Meep - Feeding these to an LLM prompted to extract a username should produce the same output.

- Base Input:

- To Test

- Modify a base request/response (e.g. from normal operation or usage) with a bit of negligible natural language context. For instance, instead of

https://example.com?status=active, tryhttps://example.com?status=The%20status%20is%20active. - Compare the new response with the base response. If the response is the same, this likely indicates an LLM is used.

- Modify a base request/response (e.g. from normal operation or usage) with a bit of negligible natural language context. For instance, instead of

- What iz it?

- Time-Based Testing

- What iz it?

- LLMs take a longer time processing words compared to traditional methods. We can leverage this to detect the presence of LLMs by feeding small versus large input.

- To Test

- Submit two responses, one with short input (e.g. 1 word), and one with long input (e.g. 1000 words).

- If the response time is dramatically different, this may indicate an LLM is used. For instance, the short request takes 3 seconds, but the long request takes 30 seconds.

- Obtain more datapoints and plot a linear regression of time against number of words in response. In our observations for an API wrapping GPT-4o, we observed a word rate of roughly 83 words per second.

- What iz it?

Advantages:

- Black-Box

- Applicable to red team scenarios, black-box pentest engagements, poorly documented environments, etc.

- Opsec-Friendly

- Unlikely to trip alerts or unintentionally trigger commands/functions.

- Short, low textual overhead.

- Blind Prompt Injection

- Allows detection of prompt injection even if LLM output is not returned in an HTTP or out-of-band response.

- Easy to Automate

- Left as an exercise for the reader.

Limitations:

- Input fields may have special parsing rules which highlight keywords. For instance, a search query may discard stop words ("the", "is", "a") and focus on keywords instead.

- The backend may be using a simpler NLP model instead of an LLM. Some chatbots do this.

- Time-based testing is dependent on various factors, including the AI's initial prompt/task, the implementation, and server hardware.

Footnotes

Not sure how relevant this is, but with our output-invariant and time-based prompts, the prompting tone tends to be passive rather than active. Instead of giving the AI an explicit direction or posing a question, we're simply stating a normalcy. In English terms, our prompt is a declarative sentence, rather than an imperative or interrogative sentence. From my observations, this seems to have a higher rate of success with minimal effort. With imperative prompts, I often find myself cajoling the AI (which can be an immense time sink). ↩︎

In hindsight, a better metric in this case would be "End Response Timer" minus "Start Response Timer", since our target LLM would stream text. This should eliminate some noise due to other computations in the wrapper. ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.