Why Dynamic Memory Allocation Bad (for Embedded)

If you need flexibility and can afford it, use dynamic memory. If you can’t afford it, use static.

Getting better hardware is not always the solution. Sometimes; but not always. Don't be clueless.

I keep explaining why dynamically allocating on embedded systems is a disagreeable idea, so thought I’d throw it on a post. This is a confusing topic for many junior developers who were taught to use new and delete in early C++ courses. In desktop/web application programming, dynamic allocation is everywhere.1 Not so in embedded.

To clarify, dynamic memory allocation (in embedded) isn't always bad, just as goto isn't always bad. Both dynamic allocation and goto have appropriate uses, but are often misused. As engineers, it's our duty to understand which situations call for these features and to make sound choices.

Clueless software engineers thinking "the more advanced the concept, the better". Don't be clueless.

Not only is allocation an issue. Virtual classes, exceptions, runtime type information (RTTI)—these are all no-nos for some embedded companies. They're all avoided for the same reasons: performance degradation and code bloat. In essence, not enough time and not enough space. With dynamic memory, there's another reason.

So why is dynamic memory bad?

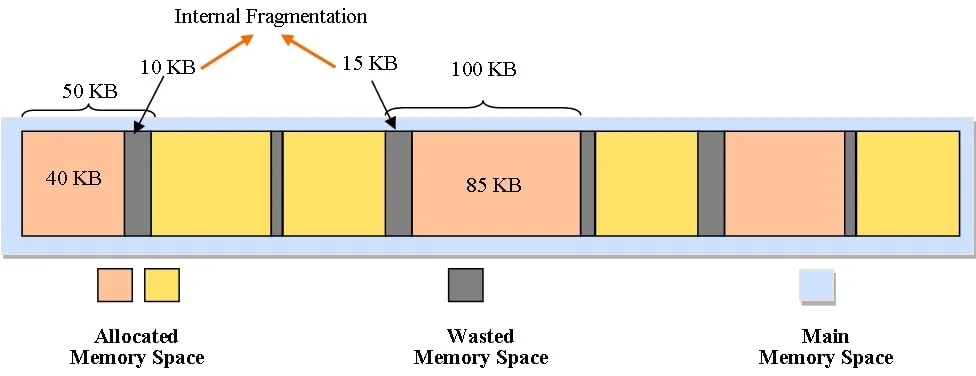

Because of Memory Fragmentation. This occurs when we keep allocating and deallocating memory in various sizes. This may lead to wasted memory, leading to slower allocations (due to the need to reallocate and compact memory) or our worst nightmare: an out-of-memory exception. 🤯

Memory becomes fragmented after multiple allocs and deallocs, leading to wasted memory space. (source)

Since embedded systems tend to require sustained uptime, constantly using dynamic memory may lead to highly fragmented memory.

This is a serious issue. Persistence, backup, and resets should be considered when developing embedded applications, but buggy resets—say, due to OOM crashes—should be avoided. Maybe not an issue if you're working with missiles though.

What alternatives are there?

In C, dynamic allocation is largely optional; you, the programmer, have more control over memory usage.2

In C++, it's more of a hassle. Dynamic memory allocation is core to many standard library containers: strings, vectors, maps. The Arduino String also uses dynamic memory. No doubt, these libraries are immensely useful for organising and manipulating data, but they come with dynamic allocation.3

The alternative is to use static allocation. Instead of allowing containers to grow unbounded, we limit their size with a maximum bound. Sometimes, it's as simple as changing array declarations.

With complex data structures, more work is needed to eliminate dynamic allocation. This is what ETL containers achieve, as opposed to STL containers.

The ETL (Embedded Template Library) is an alternative to the C++ standard library, and contains many standard features plus libraries useful for embedded systems programming (e.g. circular buffers).

Here's a quick preview with vectors:

One benefit of static allocation is speed. With dynamic, allocators need to figure out size constraints and reallocate. If the allocator is good, it may perform better by using smart strategies (e.g. reusing a previously freed bin); but this still introduces overhead. With static, memory is either pre-allocated (in the case of global variables) or quickly allocated with a single instruction (subtracting the stack pointer).4 Hence, better performance at the expense of flexibility.

What about polymorphism? Like dynamic memory allocation, dynamic polymorphism also introduces performance overhead via additional indirection (dynamic dispatch, vtable lookup).

The good news is: static polymorphism exists! In C++, we can achieve this via CRTP; but we lose the ability to declare polymorphic containers, such asvector<Animal*>, vector<Shape*>. We could also use sum types (e.g. std::variant); but this would increase memory footprint. Sometimes virtual classes are a necessary evil abstraction.

Thus, it’s crucial to consider the design requirements of the software being developed. How long do the strings need to be? Can they be limited by a maximum length? How many items will our vector hold at most? Is it more maintainable to use virtual classes here?5

Is dynamic memory always bad?

Dynamic memory isn't bad in all cases, if used properly. Some appropriate situations:

- You only allocate during init. For example, we allocate memory based on a setting from an SSD card.

- It's difficult to decide on a maximum bound at compile time. It's easy to cap small strings at 32, 64, or 256 chars. But what about HTTP requests? JSON payloads? These vary a lot between applications, so libraries typically default to dynamic allocation.

There are various ways to implement dynamic memory allocation. The "best" method depends on your specific scenario. Memory pools are one implementation admired for their simplicity and lightweight nature. FreeRTOS documents other heap implementations which aim to be thread-safe. Heap 4 is of particular interest, as it mitigates fragmentation.

Summary

In a recent discussion between Uncle Bob and Casey Muratori on clean code and performance, Bob summarises:

Switch statements have their place. Dynamic polymorphism has its place. Dynamic things are more flexible than static things, so when you want that flexibility, and you can afford it, go dynamic. If you can't afford it, stay static.

(source; emphasis added)

This applies to embedded system memory as well. It’s difficult to afford dynamic things with few resources. With more powerful MCUs, it’s easier to justify dynamic things, be it heap, polymorphism, and whatnot. In the end, we should take into account the available resources, design requirements, and use cases. Let me summarise again.

If you need flexibility and can afford it, use dynamic memory. If you can’t afford it (as is often the case), use static.6

Footnotes

Even if you don’t use it directly, it’s still there. Most garbage-collected languages (think Java, JS, Python) will allocate primitives on the stack, and all other objects on a heap. ↩︎

Also, the C standard library rarely depends on dynamic allocation; except maybe for file IO. ↩︎

Sure,

stdcontainers allow custom allocators, and that can be a topic for an entire series of posts... but it also means additional indirection, whether at compile-time or runtime. ↩︎And if your function uses multiple statically-allocated variables, the allocation will be combined into one giant stack subtraction. You can thank your compiler for this. ↩︎

What's the right balance of maintainability? Is it worth sacrificing maintainability for performance? ↩︎

The distinction between want and need is small, but IMO important when programming for embedded systems. Sometimes, we may want to use the heap, but it's not needed. Very rarely, we may need the flexibility of the heap since the benefits outweigh the costs. ↩︎

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.