AOC 2021 Haskell Utils

An introduction and walkthrough of my haskell utilities.

Haskell, despite its relatively low popularity, is quite up to speed on language features and tooling (unlike–cough cough–some other languages). One of these features is being able to separate and organise files into modules, encouraging clean code practices and cleaner development.

In Advent of Code (AOC) 2021, I found it useful to separate common functions into a Utils.hs file. After all, to make our environments cleaner we should reduce, reuse, and recycle.

I'll introduce some basic utilities first before moving on to advanced ones. However, I won't make too many attempts to teach the basics. For that you may refer yourself to Learn You a Haskell (LYAH), which provides a very nice tutorial into Haskell.

List Utilities

count :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> Int

Typically, the situation arises when we need to count the number of elements in a list. For example, "count the number of occurrences of 3 in [1, 2, 3, 4, 3, 3, 5]". To do this, we'll filter the matching elements, then take the length of the filtered list to count the number of matches.

If you're new to Haskell, you're probably wondering "what the heck are the jumble of symbols on the first line?" It's the type signature! We can roughly translate it as follows:

count: Thecountfunction...::: has the following type...(a -> Bool): it takes a predicate; here, a function which itself takes a generic typeaand returns a boolean...->: then...[a]: it takes a list of generic objects (all the same type as the previousa!)...->: then...Int: it returns a 32-bit integer.

Well, this isn't entirely accurate due to currying, but it's a decent mental model.

In the type signature, a is a generic type, similar to template parameters in C++ and generics in Java/Scala (although the convention in those languages is to use T and A).

In Haskell, there is actually a more concise way to write count:

. stands for function composition, similar to those in math ($f \circ g$). On the practical side, it applies the right-hand-side function first, followed by the left-hand-side function. Programs are all about combining small operations to form bigger ones, so you'll see . being used a lot in purely functional code.

In the code above, you can think of count as taking one parameter p :: a -> Bool and returning a function [a] -> Int which is the composition of length and filter p. It may help if I refine the type signature, so that it's clear that it returns [a] -> Int:

So we can actually think of count as having several types:

- it takes a

(a -> Bool), a[a], and returns anInt; or - it takes a

(a -> Bool)and returns a([a] -> Int).

Either way the function does the same thing. Under the hood, however, the Haskell compiler thinks using the latter version. This phenomenon is known as currying and its flexibility is quite useful for creating partial functions.

firstBy, lastBy :: (a -> Bool) -> [a] -> a

Both firstBy and lastBy have similar function types: they take a predicate (a -> Bool), a list [a], and return an element a. You can probably guess what these do by just looking at the names and types.

even checks if a number is even. < 4 checks if a number is less than 4. We could be more explicit: lessThan4 x = x < 4; but < 4 is just more concise.

These functions are useful when we've generated a list of possible solutions, but only want the first or last element which meets some criteria.

fromBinary :: String -> Int

As you could guess from the type signature, this function converts a binary string to the corresponding base-10 integer. You'll notice that we didn't give a parameter name for String, and that's because we curried foldl (which takes up to 3 parameters).

Folds in functional programming are powerful and useful because they are generalised/abstract constructs. And like all generalised/abstract constructs, folds take a bit of time to understand. If you know how reduce works, foldl is similar. You can learn more about folds in LYAH's chapter on folds.

To illustrate fromBinary in action:

digitToInt is a function defined in Data.Char which converts a char digit ('0'..'9') to the corresponding integer 0..9.

Debug Utilities

Debugging in the functional world is slightly more nuanced than debugging in the imperative world. Haskell's Debug.Trace library—with its signature function trace—allows us to print messages to standard output, bypassing the restrictions of pure functions. Some examples of trace in action:

The first parameter of trace is the string to output. The second parameter will be returned as is, without modifications.

In foo, we define the tracing on a separate line so that it's easy to comment out. The first match uses guards (see LYAH).

Here are some convenience utilities that may spare a few keystrokes:

(++$) :: (Show a) => String -> a -> String

So that we don't have to write show for every non-string item we want to print. We can use this in foo's trace message to replace ++ show n with ++$ n.

It's a bit superfluous, but I think writing show all the time bloats the debug message.

trace' :: (Show a) => a -> a

A helper to print and return its argument, to avoid repetition.

Advanced Utilities

In the following sections, I'll talk about fundamentals less so that I can focus more on the higher-level things. I'll presume the reader has a solid grasp of fundamentals.

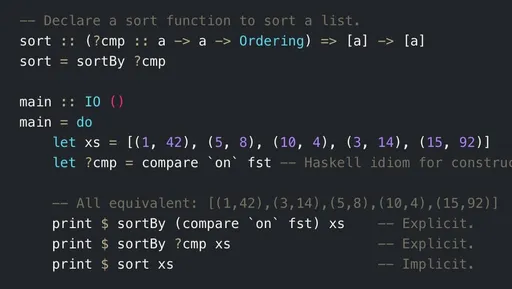

counter :: (Hashable a, Eq a) => [a] -> M.HashMap a Int

This helper function takes a list and counts the number of occurrences, packing it into a hashmap for efficient lookup.

After all, if Python has such a convenience (collections.Counter), why shouldn't Haskell have something similar?

In fact, we can generalise this to not only work with lists as input, but for any Foldable type. This is what we would get if we let the Haskell's type inference work its magic:

That is:

I used the strict hashmap provided in the unordered-collections package, but it should work with lazy hashmaps as well.

If you want to use the Hashable typeclass in code, you'll need to jump through some hoops by "exposing" the hidden hashable package and importing Data.Hashable.

Parser Utilities

I used MegaParsec this year, but the idea of the following utilities can also be applied for other parser combinator libraries.

digits :: (Num i, Read i) => Parser i

Convenience function for parsing a number (string of digits).

integer :: (Num i, Read i, Show i) => Parser i

Convenience function for parsing a (possibly negative) integer.

AOC-specific Utilities

Some more utilities which I wrote solely for AOC.

defaultMain

This utility may seem scary since there it's packed with other user-defined utilities. But to summarise, this function helps standardise the AOC part 1/part 2 structure while also providing the option to specify input files from the command line. This is useful as Haskell Stack is a bit fussy and long-winded when it comes to compilation.

One thing I found useful was having flexible parse methods. Sometimes I want to parse using a String -> a function because it was enough to simply do map read . lines. Other times I want to parse using a Parser a combinator due to more complicated syntax in the input. Thanks to ad-hoc polymorphism, we can achieve this using typeclasses; and so the ParseLike typeclass was born:

Here's an example usage from Day 1:

Other usage examples can be found in my Haskell AOC solutions.

criterionMain

Criterion is an excellent benchmarking library with various config options and output formats. To integrate Criterion with my pre-existing options, I hand-spun another default-main for benchmarking. So instead of passing my parsed input to part 1/2 functions, I pass it to benchmarks.

Example usage from Day 22:

Comments are back! Privacy-focused; without ads, bloatware 🤮, and trackers. Be one of the first to contribute to the discussion— before AI invades social media, world leaders declare war on guppies, and what little humanity left is lost to time.